Publishing director: Sarah Lavelle

Creative director: Helen Lewis

Commissioning editor: Cline Hughes

Designer: Emily Lapworth

Production director: Vincent Smith

Production controller: Tom Moore

Published in 2017 by Quadrille,

an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing

Quadrille

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

quadrille.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

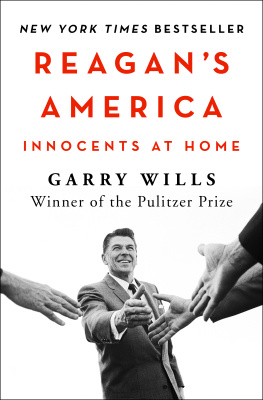

Text Dixe Wills 2017

Inside illustrations David Wardle 2017

Design and layout Quadrille 2017

All images on jacket iStock, except

A Meeting of Umbrellas on the front cover Heritage

Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

eISBN: 978 178713 203 0

Pour O

Le cur a ses raisons, que la raison ne connat point.

Contents

It might be difficult to believe when reading the news but the Britain we live in is not entirely shaped by the whim of the government and the decisions of ministers blessed with varying degrees of wisdom, but very often by tiny, apparently insignificant events. The wars the nation has fought, the great advances made in science, the food we eat, the music we listen to and the politics that shape our daily life all of these have been governed to a certain extent by incidents or events that may have appeared completely inconsequential at the time.

For example, theres the split-second decision that could just as easily have gone another way, with completely different consequences; the small gesture of defiance carried out by an ordinary man or woman that sparked a movement or even a revolution; the chance meeting of two people whose subsequent work together far exceeded the sum of its parts; the moment of carelessness that resulted in a catastrophic defeat or disaster or, alternatively, brought about some extraordinary discovery that would not otherwise have been made; or the idea nurtured in obscurity that blossomed into something astonishing.

In Tiny Histories we go behind the scenes to look upon a host of fascinating and extraordinary stories of seemingly trivial events that have had enormous repercussions, in many cases moulding both the society we live in today and the people we are. Its a surprisingly little-known fact, for example, that we owe the existence of the greatest scientific manual ever written to a wager in a coffee house that didnt even involve the books author. The signing of the document that laid out for the first time the rights and freedoms that all Britons should enjoy came about as a consequence of a previous kings fatal desire to eat a large number of an eel-like fish. Much of British politics in the 1960s and 70s was determined by the shifting in the schedules of a television show, and an interview on a sports programme. The reason why its easier to make jokes in English rather than in German is all down to a disastrous decision taken by an obscure local leader in Essex in 991. Meanwhile, science fiction was invented because a duchess liked to tag on little extras to the books she wrote on natural philosophy.

I should perhaps emphasise that this is not a book of what ifs those speculations on what might have happened if only some event had turned out differently (yes, OK, we get it had Hitler conquered Britain, life would have been a bit rubbish). The examples contained within these pages are arguably even more extraordinary than their counter-factual cousins because we can see for ourselves what effect theyve had on the nation (and often the world beyond) without indulging in a moments conjecture.

Finally, I hope that the events in Tiny Histories are an inspiration to us all. If nothing else, they show that any one of us however insignificant we may feel may yet come to have an impact on the world that is far greater than we might possibly imagine.

Dix Wills

Famously decried by Motown soul singer Edwin Starr as being good for absolutely nothing, war has nonetheless proved itself a disturbingly easy state for the British to get into. The vicissitudes of armed conflict also make it a rich breeding ground for the sort of trivial occurrence whose repercussions are amplified and so go on to echo down the ages.

Walk across the short but well-defined causeway to Northey Island and youre travelling over a strip of land that has arguably had a greater and longer-lasting impact on the history of Britain than almost any other portion of the nation. Furthermore, the ill-advised act of chivalry that took place here has few rivals when it comes to the magnitude and scope of the consequences it produced. Not only did it result in one of the most extortionate and prolonged cases of blackmail the world has ever seen, but it determined who ruled the nation 75 years later, the very language that Britons would speak, and even had an impact on their ability to tell jokes.

None of this, however, could be guessed at on arriving at the scene today. Less than two miles away from the fishermens cottages and weatherboarded terraces of Maldon in Essex, Northey Island is a low, marshy, unprepossessing place speckled with trees. Its narrow causeway probably built by the Romans is just a few hundred yards long, threading itself out across marshland and then over the deep black mud of the river bed which, when the sun and tide are both out, shines like molten jet. It is the slenderness of this causeway that played a significant part in the events that unravelled there.

It was in the year 991 that a fleet of 93 ships led by the Norwegian Olaf Tryggvason sailed up the River Blackwater and landed on the 300-acre Northey Island, apparently having mistaken it for the mainland in the mist. Warned of the invasion, a small militia was hastily assembled by a Saxon ealdor (local leader) called Byrhtnoth. When the murk eventually cleared, Tryggvason shouted over that he and his horde would go away if they were given gold, an offer the 60-year-old ealdor rejected. Both sides then patiently waited for the tide to go out so that they could settle the matter by force of arms. Not having read their Horatio at the Bridge, the Vikings were surprised to find that the extreme narrowness of the causeway meant that a mere three of Byrhtnoths soldiers Wulfstan, Aelfere and Maccus were able to hold back their 3,000-strong army. Or so goes the tale at least. In reality, one imagines that all of Byrhtnoths small force was employed in keeping the Norsemen bottled up on the island.

Tryggvason soon tired of this and complained to Byrhtnoth that having his troops cooped up in this manner was not playing the game. The Saxon ealdor, chivalrous to a fault, agreed. He fatally allowed the Vikings to come across the causeway unmolested so that the opposing forces might fight on equal terms on an adjacent field. In doing this, he somehow overlooked the fact that his band of peasant warriors was rather seriously outnumbered. The Vikings thanked their hosts, before taking great care to butcher them almost to a man. According to an epic poem about the battle written four years later by an anonymous hand, Byrhtnoth himself was killed in the mle, pierced by a poisoned Viking spear before being hacked to pieces.