Smyth - English history: strange but true

Here you can read online Smyth - English history: strange but true full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Great Britain, year: 2014, publisher: The History Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

English history: strange but true: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "English history: strange but true" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Smyth: author's other books

Who wrote English history: strange but true? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

English history: strange but true — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "English history: strange but true" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Contents

This is a book about England. We shant venture north of Hadrians Wall for didnt Scotlands own king, Alexander II, say that ungovernable, wild men dwell there, who thirst after human blood, and whom I myself cannot tame? He did indeed, in 1237, to a papal legate in England on pontifical business. Nor shall we stray too far west, into Wales the kingdom known to the Romans as Britannia Secunda, or secondary Britain.

No, we shall remain in England that land known to seventeenth-century Italians as the paradise of women, the purgatory of servants, and the hell of horses the country of St George, Richard the Lionheart and Queen Victoria (except that Victoria was mostly German, Richard entirely French, and St George Palestinian, if indeed he existed at all).

Its also a book about the English; those fine, upright people in whom Pope Gregory the Great famously saw not Angles, but Angels an observation made, by the by, while he was eyeing up slave boys in one of Romes marketplaces.

Most of all, this is a book of stories. Some are gruesome. Some are funny. Most are unbelievable. All are true. This is what history gets up to when it thinks no ones looking.

or, Really Really Really REALLY Olde England

Complete this sentence: Nelsons column is to the hippopotamus as Stonehenge is to ___. Give up? Answer at the end of the chapter

Contrary to what your schoolbooks and National Trust tea towels might have told you, English history didnt begin with William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy. English history began, not with a Norman, but with a Roger.

Roger was a pretty average individual: he stood around 5ft 11in, lived in south-east England and died alas at the age of around 40. Strictly speaking, Roger wasnt human, but nobodys perfect.

Roger lived near the pleasant West Sussex village of Boxgrove (good schools, pretty church, Zumba classes in the village hall every Thursday). We dont know much more about him than that. But then, how much will people know about you in half a million years time? Roger lived near Boxgrove around 500,000 years ago. Thats practically before humans were invented.

Roger was a specimen of the pre-human species Homo heidelbergiensis , and is known as Boxgrove Man, which doesnt quite tell the whole story; a better name would be Boxgrove Shin, as thats all that was left of Roger when we found him. Everything else we know about him has been figured out through expert analysis, beginning with the shin bones connected to the knee bone and proceeding from there. We dont know very much about Rogers day-to-day habits, although we do know that he was found in the vicinity of a butchered rhino pelvis. Make of that what you will.

As for the Roger, that can be attributed to the peculiar whims of archaeologists. Englands oldest man was named after his discoverer, Danish bone-boffin Roger Pedersen, who unearthed the shin-bone in November 1993.

Contemplating our ancient history can be mind-bending. For most of recorded history, we have simply had no idea how incredibly venerable we are as a species, as a planet, and as trace elements in a 13.7-billion-year-old universe. The seventeenth-century Irish archbishop James Ussher famously used Biblical scripture as evidence that the world was created in 4004 BC , and has been vigorously derided for it ever since.

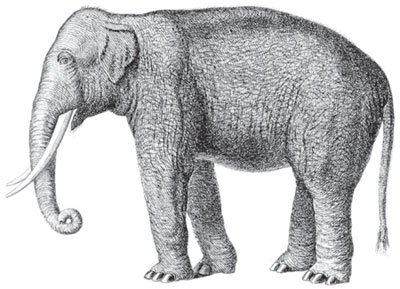

But he was far from alone in massively underestimating the amount of time we humans have so far spent here on earth. The challenge of contemplating prehistory was certainly too much for the antiquarian John Bayford, who, upon finding elephant bones and an ancient spear point near Grays Inn Road in London in 1715, assumed that the spear point had been used to kill one of Emperor Claudius elephants on the Romans entry into Britain in AD 43. He was around 398,000 years out.

Its true: elephants roamed free in prehistoric England. Long before even old Roger de Boxgrove arrived on the scene, around 900,000 years ago, the swamps of south-east England abounded with hippos and elephants. 700,000 years ago, Englands climate was more Mediterranean than Nordic; 400,000 years ago, early humans dwelt on the banks of the mile-wide Thames among rhinoceros, lions, macaque monkeys, dolphins, straight-tusked elephant, bison, giant oxen, and wolves. Meanwhile at West Stow, in Suffolk, prehistoric whiz-kids came up with a new-fangled invention called fire.

It all makes it seem as though the events we think of as history happened only yesterday. London looks and feels like an old city, but its been there for barely an eye blink, compared to the prehistoric bones that have been found beneath it: woolly mammoths down the Strand, reindeer at South Kensington station, rhinoceros at Battersea power station, and as though to cock a snook at our ideas of what constitutes history hippos in Trafalgar Square, in the shadow of that historical figure Lord Nelson.

Taking the long view, a hippopotamus is a far more representative icon of Englands history than the decidedly modern Nelson. Now theres an idea for that fourth plinth.

The first breakthrough in unearthing our prehistory came not in London, but in Yorkshire (where history is history, and dont you bloody forget it). Kirkland Cave, high in the Dales, was examined in 1822 by the Oxford academic William Buckland who found it strewn with exotic animal bones. Buckland surmised that the cave had been home to prehistoric hyenas, and was therefore littered with their leftovers (exploding an alternative thesis that attributed the presence of the bones to the Great Flood of Genesis).

Buckland was so enraptured by his hyena hypothesis that he adopted one as a household pet. He called it Billy. It had a habit of upsetting house guests by noisily crunching guinea pigs under the settee.

We cant leave the splendid and flowingly berobed William Buckland without telling a couple more stories about him.

One tale recounts that, in order to investigate the provenance of the fossilised reptile footprints found in Dumfriesshire in the 1820s, Buckland and his colleagues induced a tortoise to walk through wet pie crust. It was really a glorious sight, wrote the publisher John Murray, to behold all the philosophers, flour-besmeared, working away with tucked-up sleeves.

Another concerns Bucklands all-encompassing appetite and his stated ambition of eating every species of creature on earth. A conservative modern estimate would put that at around 3 million species, so to achieve his peculiar aim, Buckland would have had to munch his way through at least 100 species a day, every day of his life but he certainly had a good stab at it, sampling such treats as bluebottles, toasted mice, panthers and puppies, among many other creatures (sadly, his recipe book has been lost to posterity).

The apogee of Bucklands gastronomical adventuring, though, came during a high-toned dinner at Nuneham House in Oxfordshire. The meal having been concluded, his host, evidently a collector of curiosities, was proudly showing off the jewel of his collection: the embalmed and somewhat shrunken heart of Louis XIV of France, the Sun King, the grandest monarch of his (and perhaps any) age. Buckland was impressed. He was also, it seems, still hungry. I have eaten many strange things, he remarked, but have never eaten the heart of a king before. Before anyone could stop him, Buckland had gulped down the nut-sized royal offal in one.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «English history: strange but true»

Look at similar books to English history: strange but true. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book English history: strange but true and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.