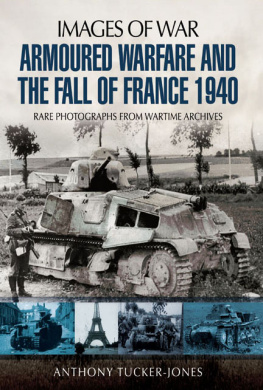

Triumphant panzertruppen seated on their Czech-built PzKpfw 38(t).

Contents

Introduction

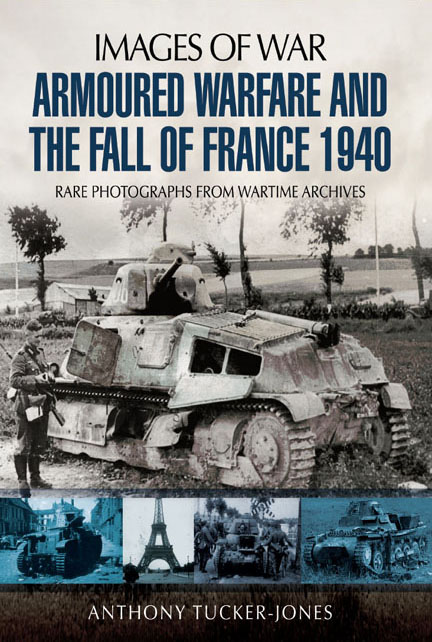

I t was in the summer of 1940 that the myth of the invincibility of Adolf Hitlers Panzerwaffe and Luftwaffe was truly created. Nothing could withstand the combined power of the panzer and the Stuka dive-bomber all fell before them in a state of sheer panic. In short succession Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and then France fell under the Nazi jackboot. Swallowing up Germanys smaller neighbours was one thing, but France should have been a much more indigestible meal for the Nazi war machine. Protected by the Maginot Line, with a large reasonably well-equipped conscript army and backed by sizeable overseas colonial forces, the average French citizen felt secure in his bed through the anxious months of the Phoney War of 1939.

At 2100hr on 9 May 1940 Codeword Danzig was issued alerting Hitlers airborne troops that they were about to spearhead an attack on Belgium and the Netherlands. The following day the Nazi Blitzkrieg rolled forward striking the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French 1st, 7th and 9th Armies in Belgium and the French 2nd Army in northern France at Sedan. Belgian, British, Dutch and French attempts to stem the Nazi tide proved futile and while the Allies enjoyed a minor success at Arras, once their reserves had been exhausted and their remaining forces cut off, Paris lay open.

It was all over by early June when the trapped British, Belgian and French troops were forced to evacuate Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne. The Germans then battled their way south and by 10 June were across the Somme. At this point Italian dictator Benito Mussolini attacked southern France, and twelve days later the humiliated French Army agreed to an armistice leaving the country divided in two.

What is so remarkable about the Fall of France is that only a year earlier the French Army was considered to be the strongest in the world. In reality, as subsequent events proved, it was fatally flawed; first, since the bloodletting of the First World War it was very short of manpower; and secondly, the French looked to the success of their earlier defensive actions against the Germans to formulate their defence policy. The heroic defence of Verdun loomed large in the French psyche.

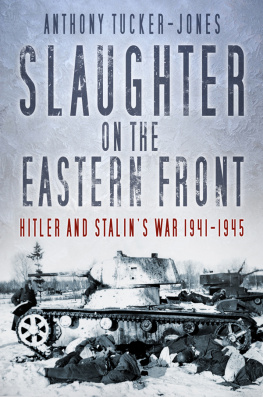

In the aftermath of the First World War the French and German Armies became a product of the economic, political and social upheavals of the 1930s. While the dynamic German armed forces became an instrument of revenge with which to punish those who had imposed the Treaty of Versailles, the moribund French armed forces remained a static defensive weapon. The Nazis arose from the ashes of the feeble Weimar Republic determined to restore national pride and Germanys military power.

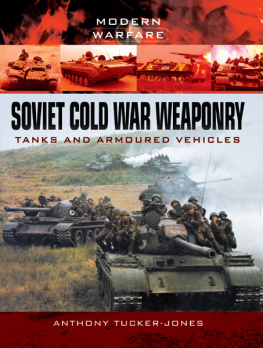

Meddling in the Spanish Civil War allowed Germany, and Russia for that matter, to test out their new tanks. These were not the lumbering support tanks of the First World War but something entirely new an overtly offensive weapon that could pierce an enemys defensive line then turn his flank. French military experts lead by Charles de Gaulle knew that they must keep up with this new military theory or face the consequences. Warfare is not just about having the equipment to conduct war, it is knowing how to use it to its maximum effect. The Fall of France in 1940 proved a salutary lesson in this.

While France may have been reasonably ahead in the arms race it lost the concepts race. During the early 1930s, while Secretary General of the Council for National Defence, Charles de Gaulle developed his idea of an armoured division supported by a tactical air force. When he published his book The Army of the Future the French were not receptive but the Germans took a great interest in his theories. in 1935 the first panzer division was formed exactly along the lines de Gaulle envisaged.

It was not until late 1938 that the French War Council decided to equip two armoured divisions on the de Gaulle pattern. By then it was far too late, the Germans mustered twelve hard-hitting panzer divisions. Hitler had made his plans and so had his Italian accomplice Mussolini. General de Gaulle was commanding the tanks of the French 5th Army in Alsace when the panzers invaded Poland. He can only have despaired as his ideas came to pass in the hands of Frances traditional enemy.

Britain was in a similar position. While the British military were keen enthusiasts of the tank following their experiences at Amiens in 1918, cost and the countrys love affair with mounted cavalry greatly slowed progress. Like the French the British developed two kinds of armoured force: the fast-moving, all-arms groups that were the basis for future armoured divisions and tank battalions assigned an infantry support role.

In 1937 it was decided to equip a number of British cavalry regiments with tanks instead of expanding the existing Tank Corps. While tank enthusiasts such as Captain Liddell Hart and Generals Fuller and Hobart designed and trained tank units that were unique in concept and technical proficiency only a very few were experienced in mechanised warfare.

Hitler wanted to attack France as soon as possible to secure his western borders in the wake of defeating Poland in September 1939 before then turning east again to tackle Russia. However, he was informed that it would take months to refit his panzers. Nearly every single vehicle needed an overhaul and depleted ammunition stocks were insufficient to ensure victory over the French Army.

After six months Hitler invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940. The outnumbered Danes offered virtually no resistance, but the Norwegians (with belated British and French military assistance) lasted until early June. France and the Low Countries (the Netherlands and Belgium) now braced themselves for the inevitable German attack.

Ironically from the very start on 10 May 1940 both the Germans and the Allies played out Hitlers envisaged campaign to perfection. The moment the German offensive commenced the Allies drove north to confront Army Group B, which in the event overran the Netherlands in the space of just five days. in Belgium other units of Army Group B shoved the Allies back after securing Belgiums much-vaunted strongpoint Fort Eben Emael. As all this played out Hitler and his generals rubbed their hands together. Now that the Allies were committed in the Low Countries and with the French Maginot garrison pinned down, Army Group A smashed through the Ardennes to reach the French coast in a mere ten days.

In the Low Countries there was a strong pro-German sentiment. In the Netherlands this extended well beyond the countrys German-speaking minority. Likewise in Belgium the, dominant French-speaking Walloon population was constantly discriminated against by the Flemish population who had more sympathy for Germany than France. In 1936 King Leopold of Belgium cancelled his countrys defence treaty with France to win favour with the Germans. On top of this the Dutch and Belgian Armies were weak and disorganised.

The Dutch, in as much as they had a defensive plan, intended to abandon the north-east of their country and form a bastion around the key cities of The Hague, Amsterdam and Rotterdam and wait for help. In the event this would consist of three French divisions; two of which were landed on the islands of Beveland and Walcheren at the mouth of the Scheldt from where they could do little to impede the Germans; another was sent to link up with the Dutch Army, but unable to get through turned back without firing a shot. The Dyle Line was never defended with the Allies barely reaching it before turning back to meet the threat of a panzer breakthrough in their rear. On 15 May the Dutch surrendered.