DUNKIRK

DIE WEHRMACHT IM KAMPF

DUNKIRK

German Operations in France 1940

HANS-ADOLF JACOBSEN

With text by

DR. K. J. MLLER

Series editor:

MATTHIAS STROHN

AN AUSA BOOK

Association of the United States Army

2425 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia, 22201, USA

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2019 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

2019 Association of the U.S. Army

Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-659-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-659-8

Digital Edition: eISBN 978-1-61200-660-4

Kindle Edition: Mobi ISBN 978-1-61200-660-4

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

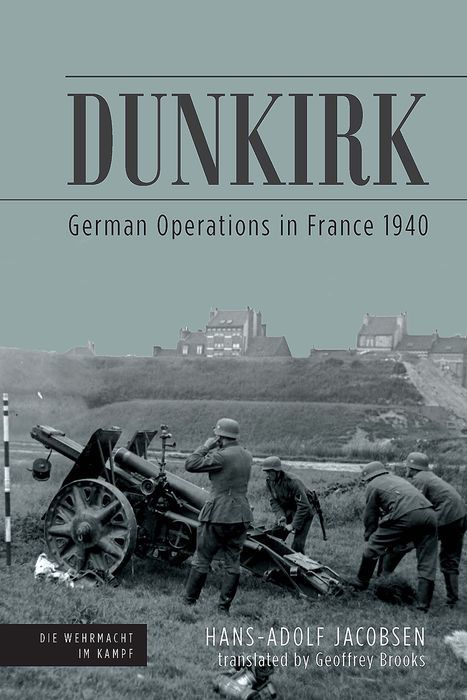

Cover image: Propaganda companies of the Wehrmacht the Heer and Luftwaffe. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-126-0310-08)

Translators Note

The German Wehrmacht was composed of the three branches of service: Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe and Heer. Heer is the German word for Army in the sense of the national Army. Army Group A for example is the translation into English of Heeresgruppe A.

Lesser than Heer and Heeresgruppe in the military structure were the many army corps XIV Armeekorps, V Armeekorps and the numbered armies, 4. Armee, 6. Armee.

The difficulty can be seen particularly in the translation of OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres = Army High Command) and AOK (Armee Oberkommando = Armee High Command), both of which occur frequently throughout the book. To avoid confusion therefore both will be referred to exclusively in acronym form.

Preface

In late May and early June 1940 a battle took place in northeastern France that had been, for many, unthinkable only a few weeks earlier: on 20 May armored formations of the German Wehrmacht reached the English Channel at Abbeville. This meant that the entire Allied Army Group 1, comprising 29 French, 22 Belgian, and 12 British divisions, with approximately 1.2m men, was encircled in arguably the biggest encirclement operation in the history of warfare. The Germans reduced the pocket step by step and this operation reached its climax in the battle of Dunkirk which raged until early June. When the weapons fell silent on the beaches of Dunkirk, the Wehrmacht had achieved an operational and even strategic victory: Belgium was defeated, and France was practically defenceless; she would not be able to hold out much longer and would surrender on 22 June. Finally, the British Army had been thrown back into the Channel and would not play a role on the continent for several years. The outcome of the entire campaign in the West had practically been decided on the beaches of the English Channel. And yet, the battle of Dunkirk has gone down in history especially in Britain as what can nearly be described as a British victory. How can this discrepancy be explained? The British succeeded in evacuating the bulk of their expeditionary force back to England although they lost all of their equipment and so the British Army did not vanish on the shores of the Channel. The Belgians and the French were less lucky and most of them fell into German captivity. But why did the Germans let the British escape? This question has been debated ever since the last British boats left the beaches of Dunkirk. Over the years, several views and arguments have been put forward; for instance, that Hitler did not want to humiliate the British, or that Hermann Gring had promised that the German Luftwaffe could give the British Army the coup de grce.

The academic debate surrounding this topic was opened in Germany with the book that you, the reader, are currently holding in your hands in the English translation. It was published in 1958 in a series that covered many important battles of the war. Most of these volumes were written by former senior officers. This book on Dunkirk was not. It was written by a rising star on the German academic firmament, Dr (later Professor) Hans-Adolf Jacobsen. After his military service in World War II and five years in Soviet captivity as a prisoner of war, he went to university and gained his PhD with a thesis on the German plans for the invasion of the West in 1940. In 1969, he became a full professor at the University of Bonn and, for many years, he was one of the most prominent historians in Germany. The same can be said of his adlatus , who wrote the sections of this book on the Allied actions and reactions. Dr (later Professor) Klaus-Jrgen Mller in his later life became a doyen of the academic study of the period of National Socialism.

The fact that they approached the topic through their academic lens gives it a different perspective to that of many other books in this series. And yet they did not regard their arguments as finite. For the historian, sources are the spring of life and, in 1958, the authors did not have access to all the files required to write an all-encompassing history of the battle of Dunkirk. Many of the relevant sources had been requisitioned by the Allied powers in 1945 and, at the time of writing, were still being held overseas. It would be the task of future generations of historians to analyse these sources once they had been returned to Germany.

This means that there are gaps in the analysis and the authors were the first to acknowledge these they do so in the foreword to the book. This begs the question: why is this book still relevant? It is relevant for a number of reasons: first, it shows the understanding of the battle of Dunkirk from a predominately German perspective as it was understood in the late 1950s. This in itself makes it a significant source. The most important aspect is, however, that the authors were able to utilise the knowledge and understanding of former German senior generals who had held important positions in 1940 the names are listed at the end of the authors foreword. So, albeit indirectly, the book offers a path into the mindset of the German military leadership in 1940 and the views and ideas that these officers had held in 1940. It is this fact in particular which makes the book relevant even today.

Dr Matthias Strohn, M.St., FRHistS

Head Historical Analysis,

Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research Camberley

Senior Lecturer,

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

Reader in Modern War Studies,

University of Buckingham

Foreword

The correct historical account provides the harshest criticism.

MOLTKE

The miracle of Dunkirk in 1940 will probably always be one of the most significant and fascinating research problems of World War II. The achievement of the Allies in retrieving 360,000 men of their expeditionary force from the Flanders Pocket was almost as brilliant as the planning and execution of the German offensive in the West itself.