About the Book

When Britain declared war against Germany in September 1939, thousands of young men sailed across the English Channel to fight for their country. Among them were the seven soldiers who share their stories in this book. Some joined up out of patriotism, others for adventure or the prospect of a secure wage. They were fit, trained and proud to wear the armband of the British Expeditionary Forces.

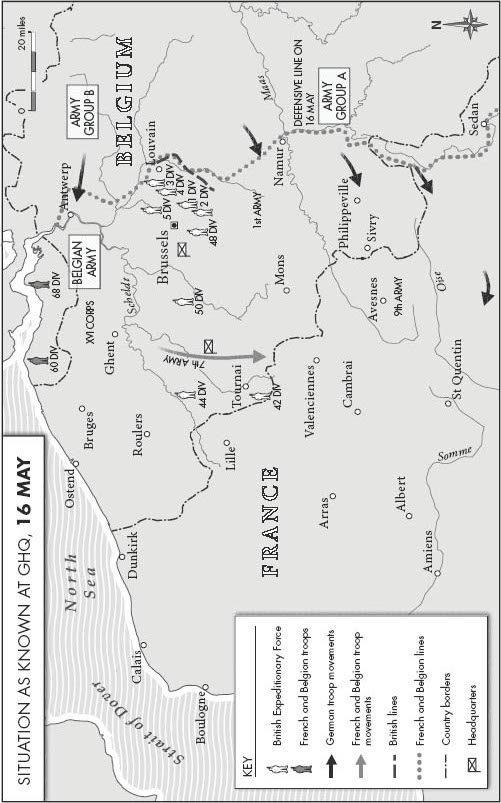

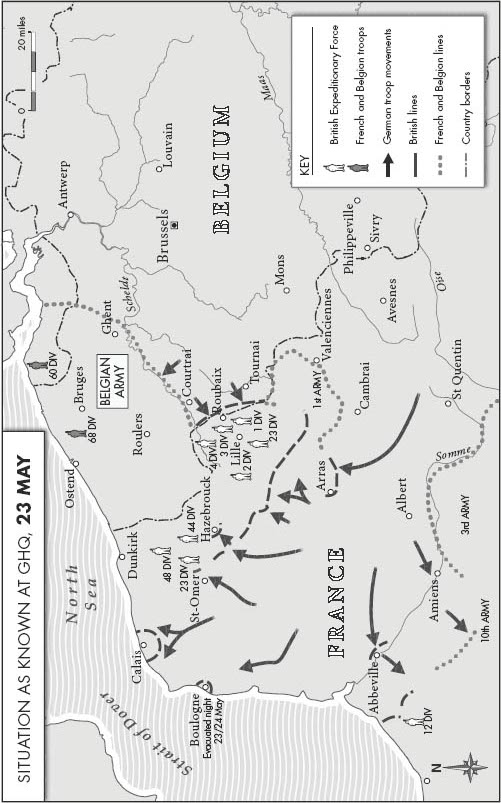

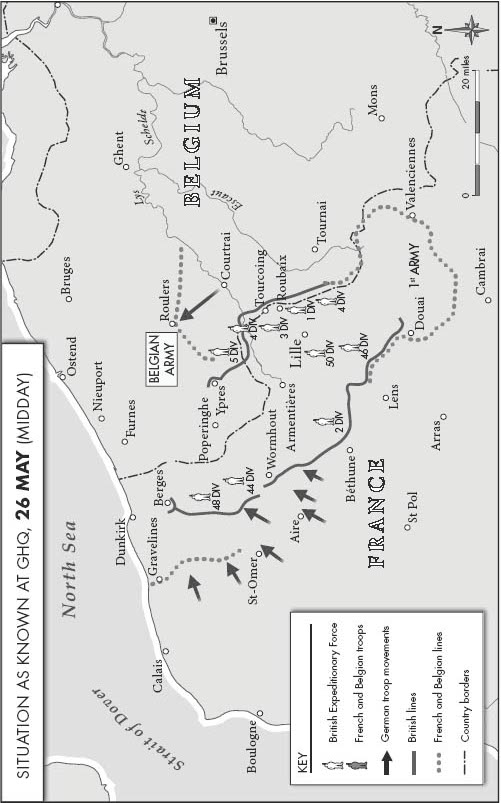

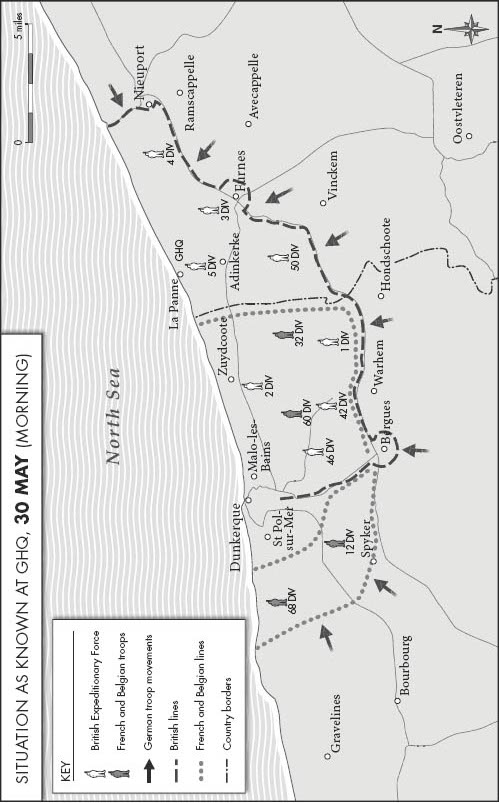

For many the first months were strangely peaceful, but when the Germans invaded in May 1940 they advanced with shocking speed. The German armoured columns sliced through neutral Holland and Belgium. The French Army collapsed and within a week the soldiers of the BEF were forced to retreat. Fighting tough and bloody rearguard actions, they endured relentless shelling and fearsome divebomb attacks. Constantly on the move, and facing a German onslaught on three fronts, they were soon exhausted, hungry and low on ammunition. They headed finally to their one chance of salvation: the beaches of Dunkirk.

Mike Rossiter tells the stories of seven veterans who went through a hellish baptism of fire in the first battles on the front line, and fought in the last-ditch defence of Dunkirk. They saw their comrades bombed and drowned off the beaches. Their accounts give us a fascinating and privileged insight into the reality of the war and what it was really like to face the German Blitzkrieg in 1940. They take us from the confident, idyllic days of the phoney war in the French countryside to the sudden shock of battle, from the fear and confusion of retreat to the wait for an uncertain rescue. These are the compelling stories of seven men who are proud to say I Fought at Dunkirk.

C ONTENTS

I FOUGHT AT

DUNKIRK

MIKE ROSSITER

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank Sydney Whiteside for the effort he put into helping me make the initial contacts with members of the Cornwall Dunkirk Veterans Association, and to the members themselves who welcomed me into their homes and told me their stories. All of them, Larry Urens, Stanley Chappell, Les Clarke, Reg Beeston and Sydney himself put up with several visits and long telephone calls as I tried to reconcile their memories with an often sparse and partial historical record. I would also like to thank Adam Harcourt-Webster and the Hospital Sargeant Major of the Royal Hospital Chelsea, Bob Appleby, for their assistance in talking to Sid Lewis and Jack Haskett.

The advice of my editor at Transworld, Simon Thorogood, and copy editor, Brenda Updegraff, was intelligent and invaluable. The book has also benefited greatly from the efforts of Sheila Lee who researched the illustrations, and from the work of Philip Lord who designed the layout. I also need to thank the photographer Rod Shone for the portraits, and Tom Coulson at Encompass Graphics who created the maps.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the help of my agent, Luigi Bonomi, and pay thanks to the patience of my wife, Anne, and two children Max and Alex.

I NTRODUCTION

AS A SMALL child I remember one of my primary-school teachers telling our class about the miracle of Dunkirk. She was an old-fashioned schoolmistress, very strict, and we children were both frightened and in awe of her. But that day, as she told us the story of Dunkirk, she was forced to stop her account by a wave of what was extremely strong emotion. I saw tears in her eyes. Whatever the personal meaning Dunkirk had for my teacher I naturally never discovered, but that moment has stayed with me and it has always coloured my view of those events. Only now, by talking to the men who were there, has it changed.

Very few of the men who were snatched to safety off the beaches are still alive. I made efforts to contact various Dunkirk veterans associations, but the only one that responded was in Cornwall. A small group of men met regularly, and there was a convenor who was able to provide me with names and addresses. I subsequently met two other men via personal contacts . But no national organization seemed now to exist.

So I travelled down to Cornwall and started talking to the men whose stories are told in this book, and I discovered that for most of them the events on the beach or in the port of Dunkirk were only a part of what they remember. Their first impressions of France were extremely vivid. At the time these were boys of just nineteen or twenty, some of whom had never travelled very far from the village or town where they were born before finding themselves in an exotic foreign country, with strange food and even stranger mores. Most of them spent some time in France and it was, as one of them said to me, like a very long holiday before the fighting started. Only one, Sid Lewis, met the German Army before they invaded Belgium and Holland, and that encounter scarred him for months afterwards. The other men were also deeply affected by what they did and saw when the fighting finally started.

What surprised me was that in the three weeks between the start of the German offensive and the height of the evacuation from Dunkirk these young soldiers were engaged in more than one intense battle and at times seemed to be permanently under fire. Naturally, sometimes they were hazy about dates and locations of the events that they remembered. It was a very long while ago, none of them could afford watches, and their officers never told them anything about where they were going or what their objective was. Anyway, as Larry Uren said, Ive been bombed so many times, Mike, that its hard to remember the specifics.

I was sure that I would be able to clarify things by looking at the brigade or battalion war diaries and the Official History The War in France and Flanders 19391940: Official Campaign History, edited by Major L. F. Ellis. I was surprised to discover, however, that the war diaries for the units concerned were produced some time after the events, back in the United Kingdom. Because of this they are written from a very partial point of view, from the perspective of the author, who was usually from the headquarters company, with the result that, for example, a minor accident to a commanding officer is reported in detail, while the loss of the equivalent of a company is never mentioned. Communication was erratic and the movements of battalions and regiments so confused at times that even when the diaries are contemporaneous they do not mention the separate movements of companies or gun batteries. Out of all the unit diaries that I looked at, only one, the 2nd Regiment Royal Horse Artillery, records the names of men killed, wounded or missing.

The Official History takes a much broader overview of the campaign, concerned with the strategic decisions faced by General Lord Gort in his negotiations with the French generals, attempting to give some shape to an enormously complicated campaign in which the Allies were always on the back foot. Written shortly after the war, the Official History tries to deal with two of the most urgent political questions raised by the retreat to Dunkirk. The first was the allegation by French generals and the Vichy government that essentially France was betrayed, and that the withdrawal of British forces gave the French no option but to capitulate. The second issue was the claim by German generals that the British Army had escaped because of wrongheaded orders from Hitler. Major Ellis deals with both claims, demonstrating that the French were overwhelmingly responsible for their own collapse, and that the German Army was not the sleekly efficient war machine that its generals, and some modern historians, seek to portray. I cant believe that these questions have such pressing importance any more, but the Official History is still the template for the majority of books about Dunkirk.

Next page