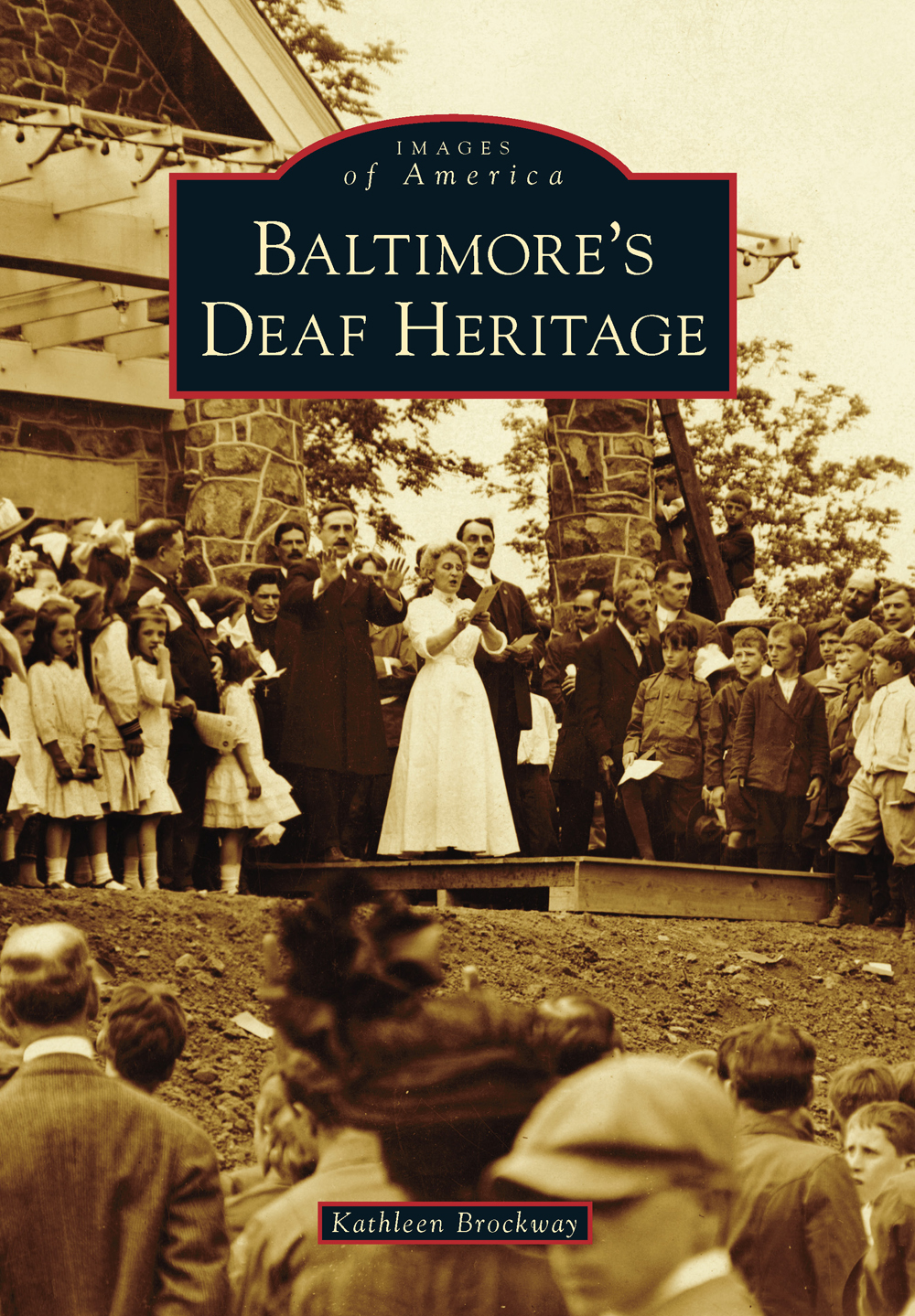

IMAGES

of America

BALTIMORES

DEAF HERITAGE

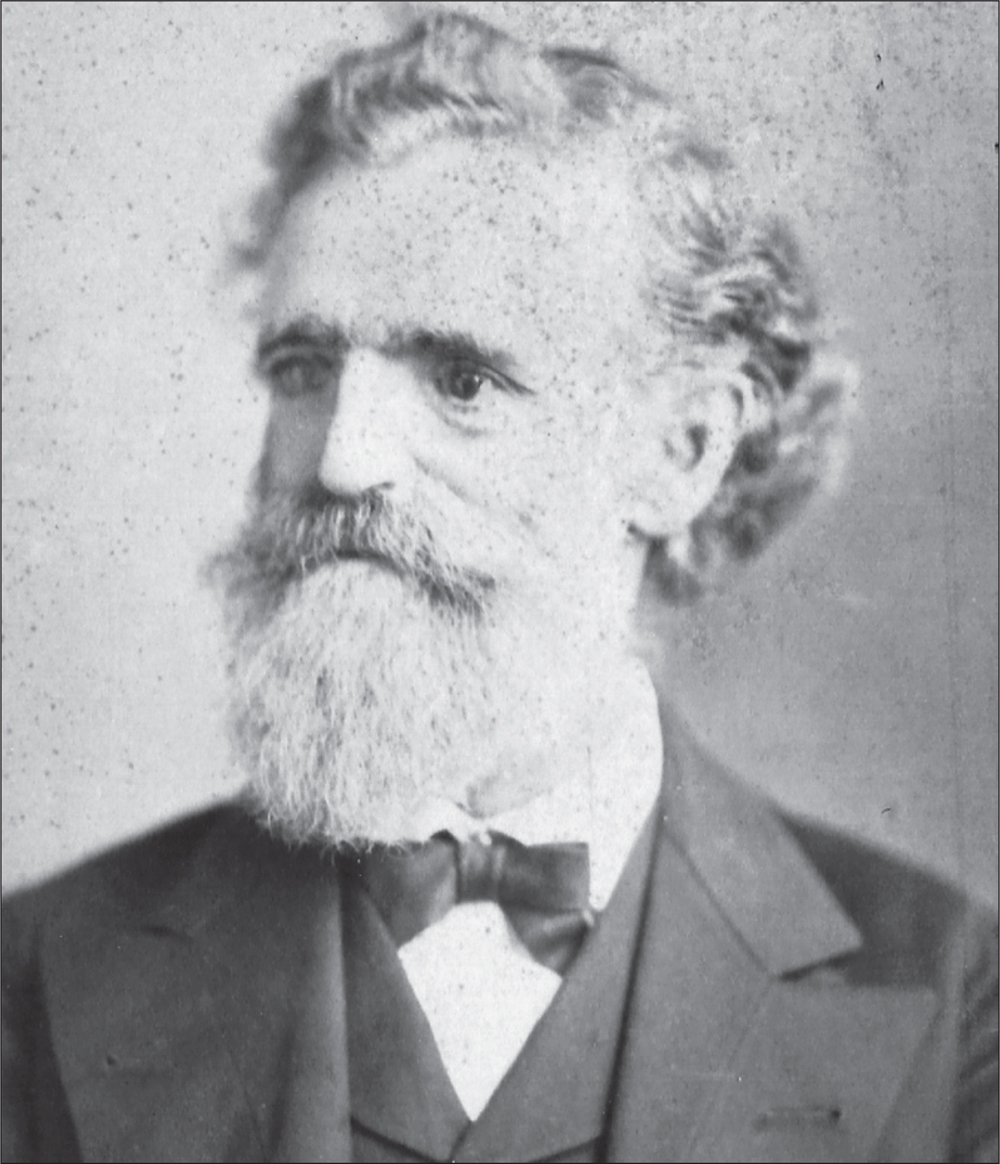

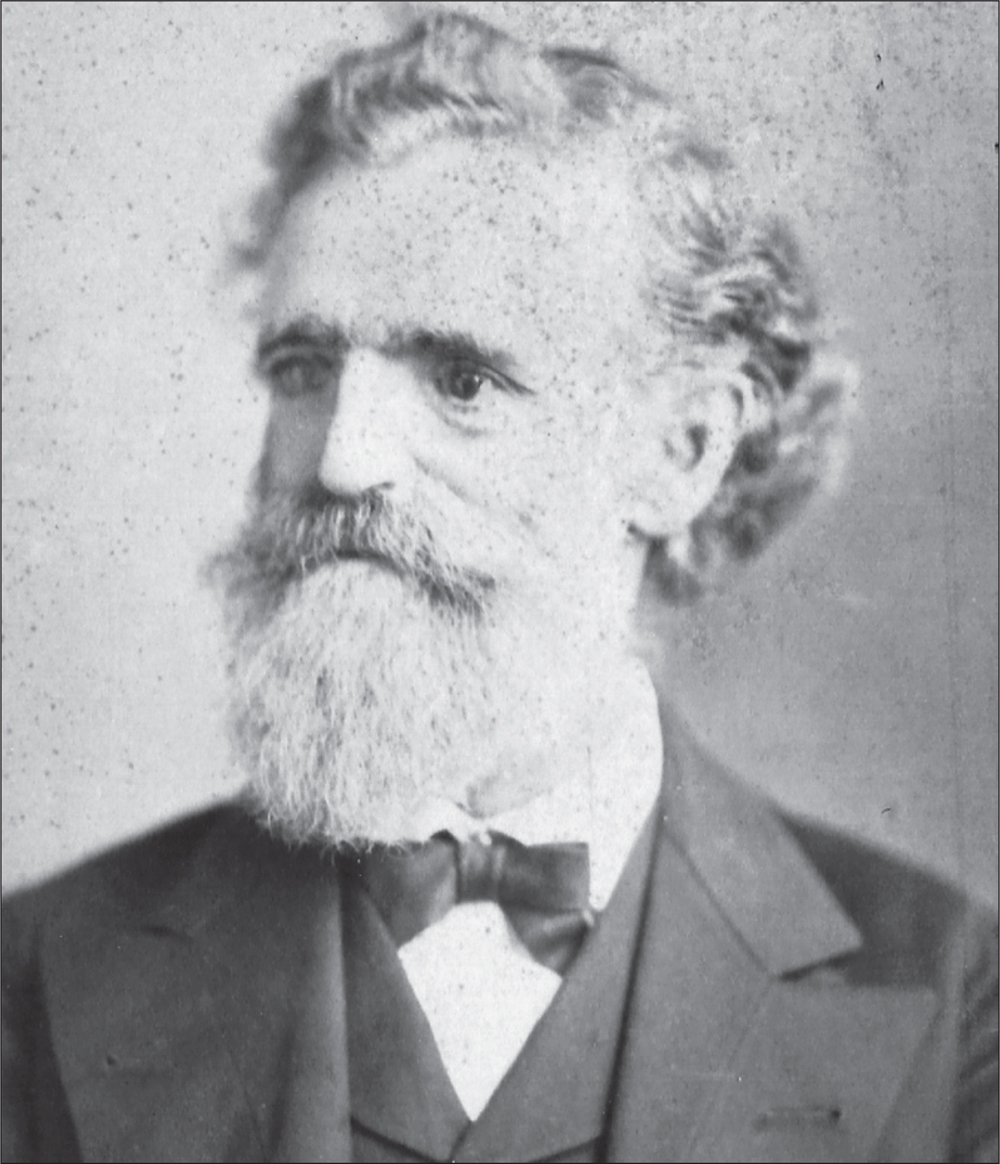

James Sullivan Wells was born deaf in 1832 in New York and attended school at New York School for the Deaf (NYSD) at Fanwood with his deaf sister Rhoda. He graduated from NYSD in 1851 with famous classmates Charles Milan Grow Sr. and Lucinda E. Hills. Grow and Hills taught at Maryland School for the Deaf (MSD) in 1868 as the first teachers. Wells later moved to Texas at the urging of Jacob van Nostrand, a fellow teacher from NYSD and the superintendent of Texas School for the Deaf (TSD). There, Wells became one of the first teachers at TSD. (Courtesy of Lee Berenson.)

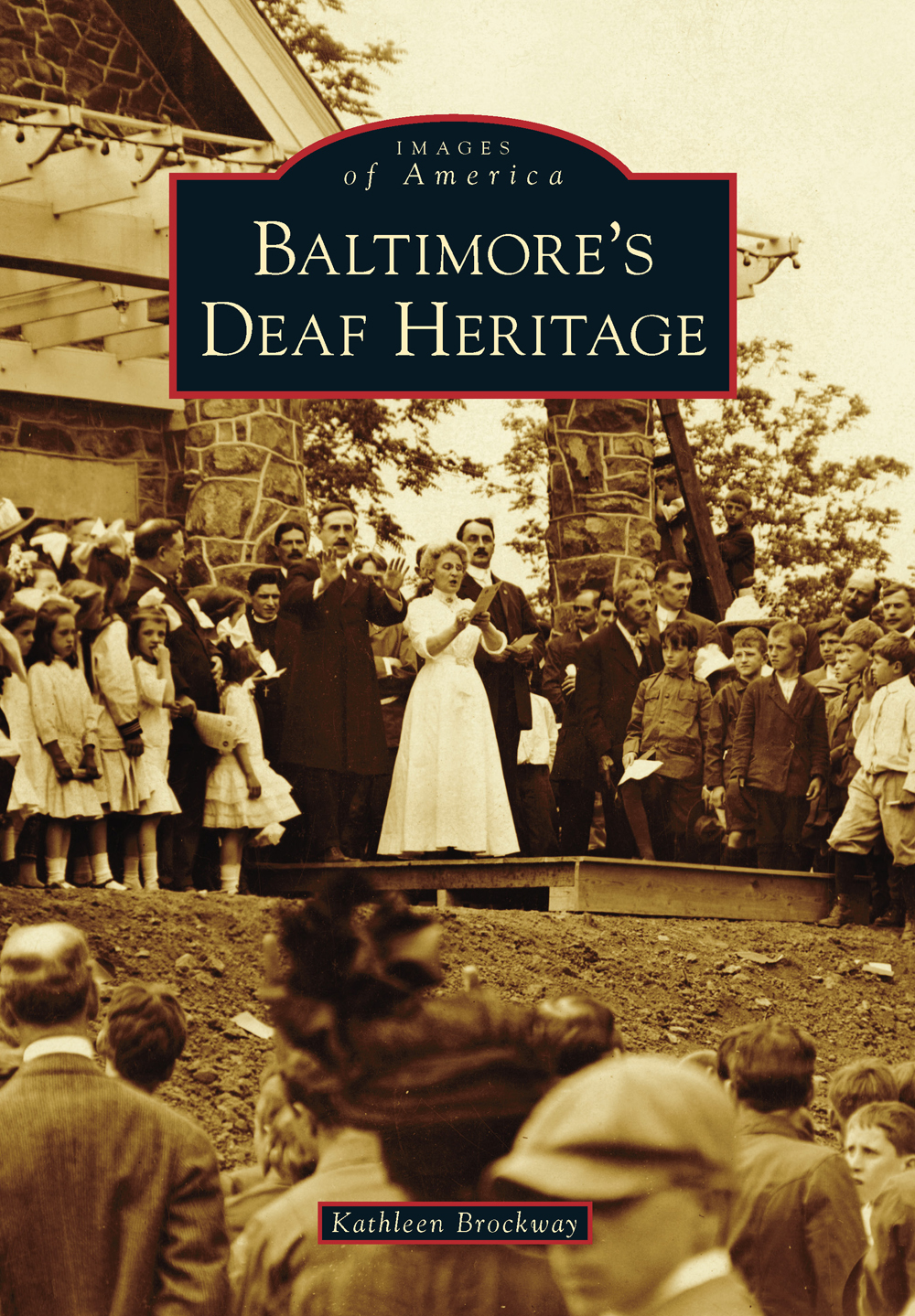

ON THE COVER: Taken in April or May of 1883 at what was believed to be one of the popular Deaf hangouts, the Druid Hills Park, this image shows someone signing to the Deaf watchers. Everybody was dressed up for the festivities on that day, either Easter or May Day. (Courtesy of Christ Deaf Church.)

IMAGES

of America

BALTIMORES

DEAF HERITAGE

Kathleen Brockway

Copyright 2014 by Kathleen Brockway

ISBN 978-1-4671-2193-4

Ebook ISBN 9781439645598

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013954120

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To the descendants of the James Sullivan Wells family, especially Lee Berenson, who was very devoted to working with me on this personal project, which made a difference in gaining recognition about more early Deaf leaders and knowledge of local Deaf history

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When I first started to know the descendants of the earliest families of Deaf leaders, I knew I had to write and share with others. Without the vintage photographs, the book would not have been possible. I wish to thank my editor at Arcadia Publishing, Julia Simpson, for her guidance and patience. There are several people who have given themselves to this book through their researching of local history. I give heartfelt thanks to Lee Berenson; Lana Leitner Butler; Elinor Reese; Milbert and Zelephiene Jennings Jones; Joyce Jacobson Leitch; Lois Cooper Markel; Eugene and Manuel Rubinstein; Charles E. Moylan Jr. and his wife, Marcia; Stacie DeLespine Wright Gill; Jeri Dilworth Miranda; Michael Olson and Christopher Shea from the Gallaudet University Archives; Chad Baker, Linda Stull, and Lawrence Newman from the Maryland School for the Deaf Museum; Michael Bina, the superintendent of the Maryland School for the Blind; Michael Hudson; Robert Geary Photography; Bishop Peggy Johnson; Arlene Blumenthal Kelly; Kathi Jeffra and Sandie Johnson from Christ Deaf Church; Alfred Sonnenstrahl; Deborah Meranski Blumenson; Simon Carmel; Harriet Grossblatt and Louis Greenberg; Fleet Bowman; Steven Brenner; Robert Herdtsfelder; Jason Dietz; Kappa Gamma fraternity members; Dr. Ernest Hairston; Paul McCardell at the Baltimore Sun newspaper; especially to Tina Koopman for her tremendous patience and encouragement; and to many more for contributing toward preserving our communitys Deaf heritage.

The following are frequently used abbreviations in the Deaf community and in this book: the American Athletic Association of the Deaf (AAAD); American Sign Language (ASL); F.F.F.S. (the abbreviation is as isit is a secret society for the Baltimore Ladies); Honor of Secret Society (H.O.S.S.); the Maryland Association of the Deaf (MAD); the Maryland School for the Deaf (MSD); the Maryland School for Deaf Colored Youths (often called the Overlea School); the Maryland School for the Deaf Alumni Association, formerly known as MAD (now MSDAA); the National Association of the Deaf (NAD); the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf (NFSD); the Southeastern Athletic Association of the Deaf (SEAAD); the Silent Clover Society (SCS); the Silent Oriole Club (SOC); the Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind (VSDB); and the Youth Silents Club (YSC).

INTRODUCTION

In 1879, at the urging of family friends, James Sullivan Wells (48) and his familyhis three small children Clarissa, Fannie, and Helen and his wife, Fannie F. DeLespine Wellsdecided to move to Baltimore, which was a new place for them away from their native New York City. By then, the Deaf community in Baltimore was starting to boom, and Deaf Baltimoreans were beginning to spend time together and worship together. Soon after Wellss arrival, he and his close family friend William Barry drew many into a group that attracted George W. Veditz, Frank and George Leitner, and many others. All became fast friends and leaders in the community, establishing events, organizations, and activities. Wells was the beginning of a three-generation family of Deaf leaders, which joined others to work together to fight for Deaf driving rights, Deaf political rights, and more. Some lived on farms, and some lived in row houses in the busy city.

Religions were varied in the Deaf community. Nonetheless, they all got together on a frequent basis, even on occasions like Easter Sunday church services, either outdoors or indoors. Getting together created a comfort zone, and they celebrated events in sign language. Deaf Jewish individuals did not always get together at the temple; instead, they hosted parties for the Deaf. In the 1800s and 1900s, the temples and other churches were difficult to attend due to the lack of interpreters and resources.

Education was important to every parent of a deaf child. Only one local school accepted deaf children under age five of all religions, the Catholic School in Baltimore. Some others received private tutoring. Schools were split in signing and oral methods, leaving it up to parents to make decisions about where to place their children. Some were sent to MSD, an all-state-expenses school that children traveled to by horse coach, train, or vehicle. Traveling to MSD was considered a long trip, so children had to stay and live on the campus, seeing their families infrequently during their school years. There was also an oral school in Baltimore that forbade sign language. Some grew up attending that school and went on to their local high schools, which did not have any interpreters. The Black Deaf community at the time had very limited choices, as students could only attend the Kendall School in Washington, DC, or the Maryland School for Deaf Colored Youths in Baltimore. Some may have not been educated at all, and worked only with their families. At the time, the Kendall School was known to teach orally. Some students paid tuition fees, while others were covered by the state if they got the governments permission. One of the first black Deaf teachers in America, Harry Leonard Johns, was from Baltimore. He taught at the Texas School for the Deaf (TSD) before returning to Baltimore, joining his deaf brother Leonard Carroll Johns in a large family on the Ostend Street.

Organizations were already starting to form by 1884. Some were set for a purpose, such as socializing, reunions, religion, political groups to fight for Deaf rights, and many more. In the 1800s and 1900s, the annual reunion cookout was a popular activity, and attendees enjoyed participating in the games and winning prizes. Games included baseball, horseshoes, and others. Groups rode the ferry together from the Maryland mainland to Bay Ridge for the cookout and swim at the beach. A bridge was built to Bay Ridge in the late 1950s.

Next page