Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Michael T. Keene

All rights reserved

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.822.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019945074

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.404.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Then Judas, who betrayed him, seeing he was condemned, repented himself, and brought again the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and ancients, saying; I have sinned in betraying innocent blood. And casting down the pieces of silver in the temple, he departed, and hanged himself. After the chief priests took counsel, they took the pieces of silver and bought with them the potters field, to be a burying place for strangers.

Matthew 27:67

CONTENTS

Thank you to Melanie, who first alerted me to this story, and to Lorraine Lucciola and Michael Leflem, who were instrumental in helping bring it to life.

INTRODUCTION

SUPERSTORM

What would become the largest Atlantic storm on record swirled violently from the Caribbean, creating a devastating oceanic force that at its zenith reached nine hundred miles across and one thousand miles long. This hurricane, or superstorm as it was later characterized, was about to lay waste to the most populated corridor in the United States. This hotter-than-usual Caribbean weather pattern met the icy North Atlantic waters and intensified into a hybrid colossus both tropical and arctic. Perhaps responding to rising global temperatures, or perhaps mythically overdue for a battle with the land, the storm was whirling and buildinghuge and slowhundreds of miles out at sea. At one point it exhibited the lowest barometric pressure ever recorded on the Atlantic seaboard. The first harbinger of destruction was 115-mileper-hour wind gusts. Across the eastern United States, people evacuated from the front lines of the inevitable destruction by the millions, responding to nationally declared states of emergency. They bought food, water and fuel and boarded up their homes and businesses, gearing up to sit out the deadliest weather event to ever hit the East Coast. For this monster storm, which would cause $65 billion in damage in the United States and kill at least 233 people, preparation was futile. For many, the impact of this superstorm would be too great to overcome. The name of the storm was Sandy.

The hurricane made landfall as a category two in Brigantine, New Jersey, bombarding the Northeast with a vortex of wind and water, spreading its massive wingspan to punish communities with rain, snow, flying debris and rising storm surges at quantities and velocities hitherto unseen in this part of the world. After drowning dozens in the Caribbean days before, Sandy set its sights on the most populated area on the continent, sending surging water up to and beyond thirteen feet in the countrys most storied island: Manhattan. The storm destroyed property, eroded shorelinesin some cases destroying 50 percent of beach sand in barrier islandsdumped ten million gallons of sewage into the water and killed twenty-five people. Hurricane Sandy revealed deep flaws in one of the worlds greatest metropolises, demolishing long-standing structures and proving that even this pinnacle of society stood no chance against this most ruinous of meteorological events. It took years, but eventually New York recovered.

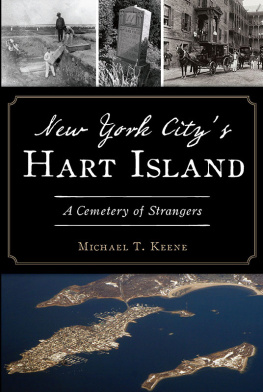

BONES BEACH

About a mile east of Pelham Bay Park and City Island off the coast of the Bronx lies 130 acres of land known as Hart Island. In April 2018, approximately six years after Superstorm Sandy, an official from the Department of Corrections, which oversees jurisdiction of the island, alerted a well-known Hart Island activist to skeletal remains that had been seen scattered on the beachsome even protruding from the shoreline! After arranging a boat, the activist and a Newsday reporter confirmed and photographed the sighting.

The following day, a forensic anthropologist from the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner conducted an investigation that resulted in the recovery of 174 human bones, including six skulls. The remains discovered that day unearthed a secret kept hidden for more than 150 years. Lying beneath the ground of this nondescript, tiny island were the remains of nearly one million people, who were buried in wide, deep pits dug by convicts from nearby Rikers Island. The dead included stillborn babies, unclaimed paupers, Union and Confederate soldiers, the insane, the addicted and the unidentified. The bones would reveal tales of war, abuse, fraud, epidemic and mental illness, which would tell the stories of New Yorks most forgotten people.

After nearly a century and a half, as the result of recent advances in DNA and fingerprint technology and forensic anthropology, and with access to previously withheld burial records, we can identify some of these anonymous lost souls and reveal the hidden history of Hart IslandAmericas largest mass graveyard.

1

THE BURIAL CRISIS OF 1822

By the early 1800s, New York City boasted a population of more than two hundred thousand, qualifying it as the largest city in the Western Hemisphere. As New York Citys population grew, so did its number of dead. What has been referred to as the 1822 Manhattan burial crisis evolved into one of the citys most troublesome and hazardous social frenzies and failings.

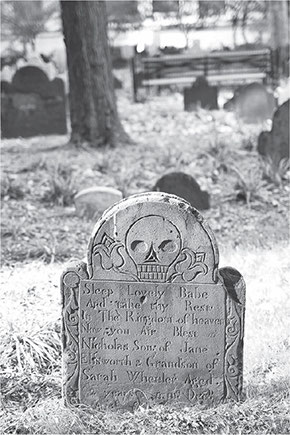

The three-hundred-year-old Trinity Church graveyard on two and a half acres of land in Lower Manhattan was the idyllic resting place of many, including Alexander Hamilton after losing his historic duel with Aaron Burr in 1804.

Today, workers in the Financial District may visit the site on breaks or lunch hours for a green, peaceful respite from offices and elevators. But in 1822, no one wanted to stroll through the cemetery. In fact, residents of the neighborhood found other routes to their destinations to avoid the place.

Why was this important in 1822?

The smell.

The all-encompassing stench.

The definitive, pervasive odor of hundreds of decomposing bodies in graves that were hastily interred only two or three feet underground.

The number of interred bodies in Trinity Churchs graveyard in 1822 was estimated at 120,000, but it was just thatan estimate. The truth was that the massive number of bodies buried in that year alone could not be tracked.

July 1822 saw the highest death rates from yellow fever in New York City, particularly in areas south and west of the church. The Common Council and Board of Health passed a resolution in August to prohibit further burials in the graveyard because of vehement complaints of offensive exhalations. Visitors to the church and graveyard, casual passersby and residents in the surrounding streets found the source of the stench unmistakable: the smell of death.