If I have to explain why we are doing this you will never understand. As usual, ThrustSSC driver Andy Green hit the nail on the head. Why was the ThrustSSC website the largest in the world in 1997, why did literally thousands of people take part in the electronic fundraiser which finally got the ThrustSSC team to Black Rock? It cant possibly be about one mans obsession there has to be much, much more to land speed racing and to speed.

We live in a risk-averse world whilst extraordinary achievements are being made with electrons and synthetic biology, they lack the sheer raw team spirit and personal risk of pushing the world speed record into speed regions which are unknown. The visual image of the high speed achievement is so divorced from current lifetime experience that the extraordinary image remains with the viewer for all time. It is easy to surmise that everyone has their personal ambition to leave a tombstone legacy perhaps not to drive a supersonic LSR car, but at least to have a claim to have been a part of such a massive team achievement.

The 1000 mph Bloodhound project took this to extraordinary levels of public benefit. Einstein had explained that the biggest hindrance to his learning was his education: current technology had advanced so quickly in his lifetime that he was constantly updating his early educational knowledge. There is a valid argument that todays educational process should make the latest educational experience immediately available to schoolchildren and this is what Bloodhound sought to achieve by making the experience and project understanding available to millions of schoolchildren in 200 countries.

Richard Noble and his team celebrating breaking the land speed record on 4 October 1983, when Thrust2 hit 633.47 mph.

We believe that such enthusiastic interest or inspiration leads to personal aspiration and enhanced educational focus. And there is plenty of precedent back in the 1960s the US Apollo moon programme spawned a dramatic increase in STEM PhDs in the USA and most probably across the world.

Richard Noble

Authors Note

It is fair to say that the modern world celebrates speed not just in terms of vehicles and travel, but in nearly every facet of life: rushing to work, walking up quick escalators or shooting up skyscrapers in record-breaking elevators to get to meetings to write fast reports and make a quick buck, earning a fast-track promotion to qualify for instant credit card decisions or quick mortgages, spending that fast cash on same-day delivery items, next-day returns, fast food, fast diets, fast fashion, speed dating, instant fame speed is everywhere. In modern life, speed is a positive, a preferred state of being, a desirable commodity.

It was speed that opened up modern society, shrunk the globe and eventually, via the internet, opened up the world at the click of a mouse. Consequently, there is now a haste to how we receive information, scrolling, liking and clicking as quickly as allowed by our broadband (a personal slice of the information superhighway that will have been sold to us on the basis of its speed). Popular culture also champions this rapidity, and is inseminated with fast car chases, fast action, fast adverts, fast music, fast lyrics we are essentially taught to embrace speed by a society that is obsessed with doing things quickly. Even a leisurely reading of a weekend edition of The New York Times presents us with more information than a thirteenth-century person would have been exposed to in a lifetime. Psychologists and counsellors quote one of the biggest single reasons given for why people need their help is: I never have enough time. In George Simmels The Metropolis and Modern Life, the writer goes as far as to state that speed has challenged time as the prime mover of modern life. There is a certain irony that, as the world gets ever quicker, many people feel they are never moving fast enough.

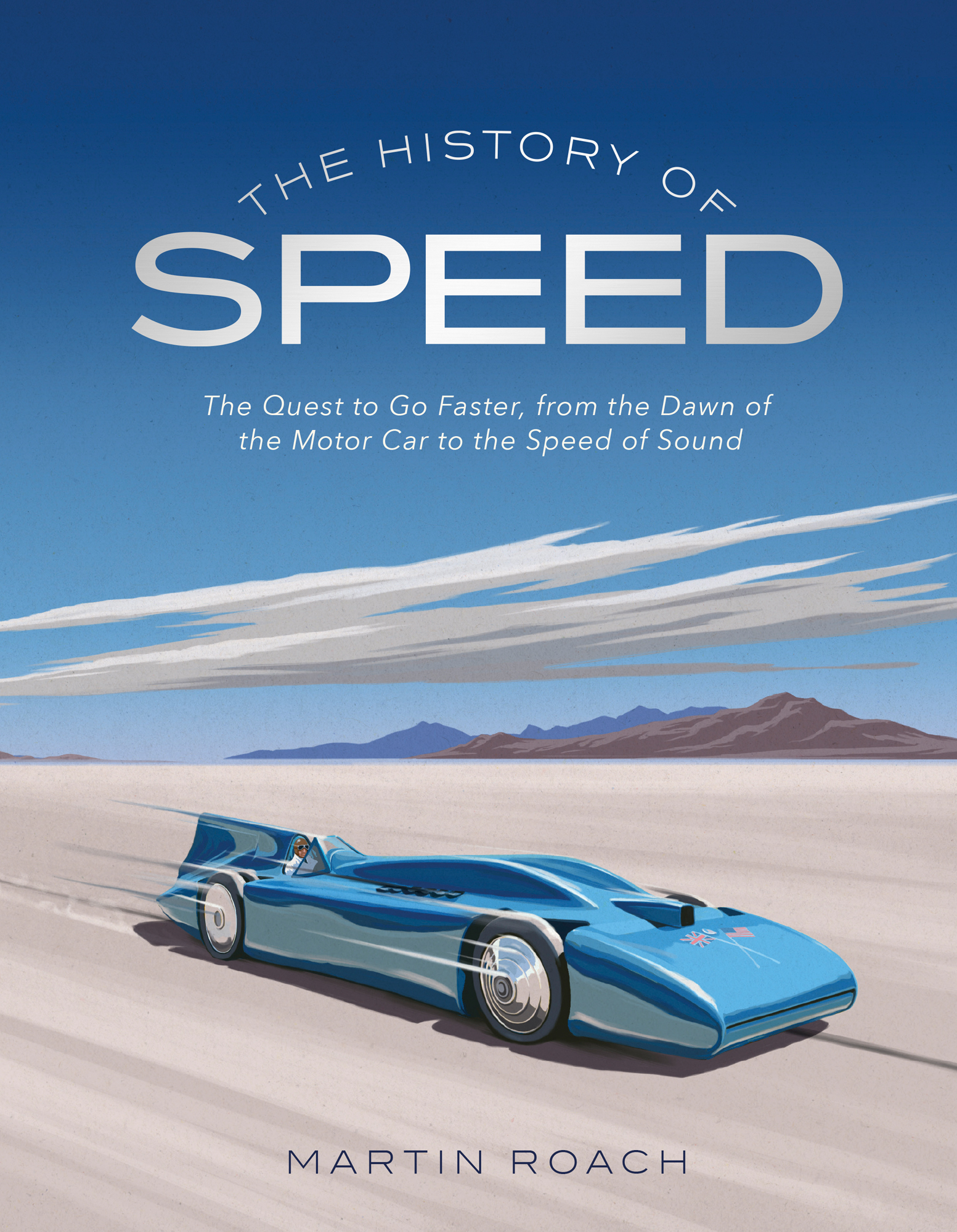

Set against this cultural backdrop, this book is a chronicle of the cars, land speed vehicles and, perhaps above all, the characters who find moving at high speed so utterly invigorating. Time and again, there are tales of speed that are most remarkable for the human narrative rather than the miles per hour on the time sheet. This book is not just about a foot-to-the-floor mentality and top speed records. Speed as a furnace of glamour, as well as its ability to bestow celebrity status, is a crucial part of the tale. The technological advances that speed has bequeathed on both automobile manufacture and society in general are also pivotal. Likewise, the gender of speed and the complex psychology of moving quickly are subjective but essential elements of the story. Necessarily, as this is absolutely not an attempt to glamorize speed, the dark side of the experience is also discussed. Finally, it must be noted that across all these historical accounts are a multitude of evolutions in society and culture, significant moments of note that have all been indelibly affected by speed.

Also, to clarify the parameters of this study, I have chronicled the active experience of speed where it is pursued as a thrill or achievement rather than a commute or base practicality. When you ask someone, What is the fastest you have ever been? they will invariably mention a speed reached in a car or on a motorbike; yet if they have been in an aeroplane, then the answer is more in the region of 500 mph. However, that is a passive experience, and as such is an example of the types of speed that fall outside the criteria of this book.

I would like to add one personal note by way of explanation: cars are my passion, so that is the prism through which I view speed; therefore this book is focused on cars or car-based vehicles, with a few necessary diversions into the world of water speed records and also motorbikes (the latter justifying a stand-alone study).

As I was completing the writing of this book in the summer of 2019, within the space of a few weeks two very significant moments in the history of speed occurred. On 27 August 2019, the fastest female on four wheels, the racer and TV personality Jessi Combs, was killed in a horrific crash in a desert in Oregon, trying to beat her own speed record and possibly eclipse the long-standing overall womens record of 512 mph set back in 1976. Jessi was due to be interviewed for this book, having become my friend in 2017 when she stayed at my home with her pals on a visit to the UK. The shock of her death was deeply felt around the world of speed.

The tragic and long list of fatal incidents in the pursuit of speed illustrates that travelling across the surface of the earth at ballistic speeds is inherently and extremely dangerous yet there is a seemingly endless queue of people lining up to take speed to the next level, sometimes at an horrific cost.

Yet at the start of the very same month, the Bugatti Chiron had become the first ever road car to pass 300 mph, when their test driver Andy Wallace hit 304.77 mph at VWs Ehra-Lessien test track. The very fact this speed attempt was sanctioned by the biggest car company in the world suggests high speed still has relevance at least to some and the way the internet lit up when the news broke, with millions of tweets and reposts within minutes of the news becoming common knowledge, indicates that, to millions of people around the globe, speed matters.