T here are so many words I could use to describe Dr Shane Kenna: academic, historian, accomplished author, historical advisor, lecturer, mentor and one of the best tour guides in Dublin, among other things.

For his family and friends, Shane was all of these things and more. From the moment you met Shane, it was impossible to ignore his love of history, especially nineteenth-century Irish history. We, his friends who worked alongside Shane in Kilmainham Gaol, got to witness that passion every day, and got to hear Shane talk about Charles Stewart Parnell or the Invincibles. We became a small, tight-knit group and, although we all moved on from Kilmainham, the friendships that had started there went from strength to strength.

Over the years, we watched Shane achieve so many wonderful things. He wrote a number of books, including War in the Shadows: The Irish-American Fenians Who Bombed Britain, Conspirators: A Photographic History of Irelands Revolutionary Underground, Jeremiah ODonovan Rossa: Unrepentant Fenian and 16 Lives: Thomas MacDonagh. He gave lectures on the national and international stage, and organised conferences on forgotten chapters in Irish history.

Shane was determined. Once he got an idea about a project into his head, he would put his all into making it a reality, as this book proves.

Shane left an impression on everyone he met. His passion for history, as well as his smile and great laugh, was infectious. He had an amazing ability to bring people together from different parts of his life, because the one thing that united us all was Shane.

There is no doubt that Shane dedicated himself wholly to his work. He was serious about the stories he wanted to tell, stories which had long been forgotten or had never before been discovered. However, although a serious historian, he did not take himself too seriously. He had a wonderful sense of humour, and with a gesture, a quote from Jean-Luc Picard or and this may surprise some a dance move entitled the Fenian Flick, Shane could lift the darkest mood.

He loved Star Trek, Doctor Who, Batman and Indiana Jones. In fact, it was seeing the professor/action hero Indiana Jones when Shane was a child that set him on the path to pursuing history as a career.

Shane was a tower of a man, over six feet tall. His stature was matched by his personality. He was kind-hearted, generous and a gentle soul, who did not refuse to help anyone with their queries, be they history students only starting out in college or relatives of those he wrote about.

I still remember the first day I met Shane, a nineteenth-century Fenian living in the twenty-first century. He was smiling from ear to ear, happy in the knowledge that he was going to be talking about Irish history every day.

This personal introduction to Shanes book has been very difficult to write, but it has also been an honour. A huge void has been left in the lives of Shanes family and friends with his passing, but if there is any solace to be found, it is that we have so many wonderful memories of him. Shane has left a legacy not just for future historians, but for those who loved him. He was a beloved son, brother, fianc, uncle, nephew and friend, and an unrepentant Fenian historian.

Liz Gillis, author and historian, 2017

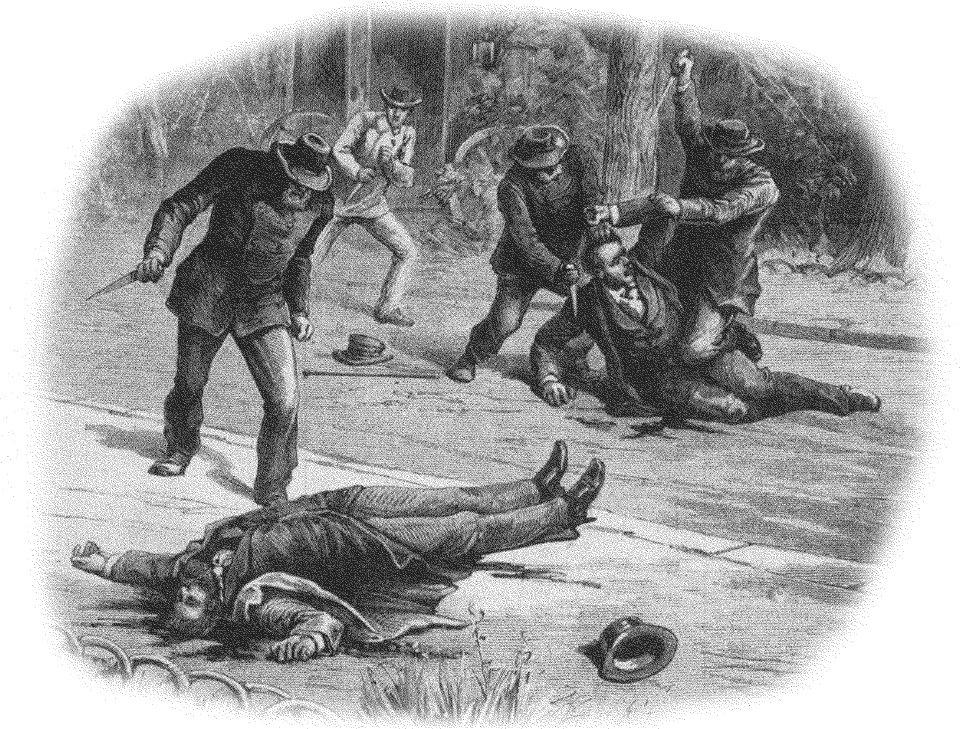

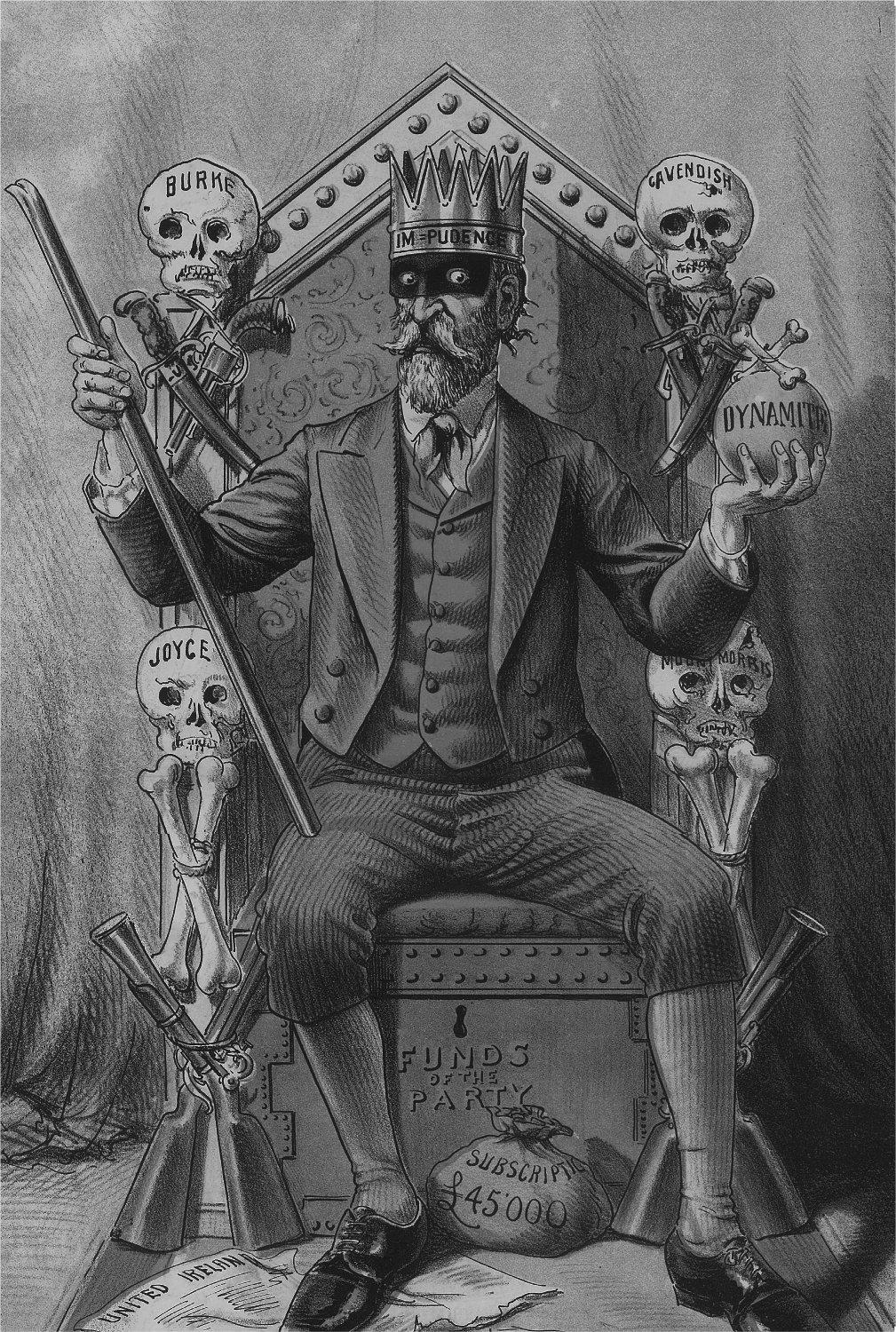

E ven by the standards of violent secret societies, the story of the Irish National Invincibles has been clouded in mystery and warped by misinformation. It has also been notably neglected, for a body that created international news in May 1882, when it assassinated two of the most senior government officials in Ireland in the Phoenix Park. Fundamental details, such as the precise name of the organisation that coalesced in Dublin in 1881, have been debated, as well as the question of its role and relationship within the broader Irish Republican Brotherhood. While the identities of the main Invincibles have been ascertained, their names have never loomed large in the popular imagination. This is surprising, given that they had members executed in 1883. These men never attained the veneration accorded to the Manchester Martyrs. In all probability, the exclusion of the Invincibles from the top tier of the republican pantheon derived in part from the magnitude of the killings they committed, coupled with the studied reticence of their associates in Ireland, Britain and the United States of America.

The revival and extremity of the physical force tradition in Ireland owed much to An Ghorta Mor (The Great Hunger) of 184550. The IRBs founders were among those who held the British Government culpable for the catastrophic death toll. The malign agency of Westminster, the sole parliamentary authority in Ireland since the Act of Union took effect in 1801, was detected in the dangerous mismanagement of the pre-Famine economy, and paltry efforts to stave off mass excess mortality, eviction and forced emigration. Veterans of the desperate Young Ireland revolt of 1848 consequently built a trans-Atlantic Fenian organisation from 1858, in order to establish a sovereign Irish Republic outside the British Empire. There seemed to be no viable constitutional path to this progressive objective, as efforts by moderates working within the proto-democratic electoral system proved time and again.

In March 1867, the Fenians in Ireland promised adult suffrage and an equitable land system, in a country slowly recovering from the privations of An Ghorta Mor and without adequate security of tenure. Attempts to achieve such ambitious objectives by force of arms were contained that year by a programme of pre-emptive police actions and effective counter-insurgency. The triumph of Dublin Castle, seat of the British interest in Ireland, aggrieved militant republicans, who endured damaging schisms on both sides of the Atlantic. Adversity spurred restructuring and new strategic thinking.

The most dramatic expressions of such multi-faceted processes were the resumed, albeit increasingly token, armed attacks on British North America from the USA. Irish-American Fenians, reorganised as Clan na Gael, humiliated London by conveying six escaped political prisoners from Western Australia to New York in 1876. In 188185, others mounted a sophisticated bombing campaign in England that badly shook the British establishment. Yet in 1884, the IRB was central to the creation of the Gaelic Athletic Association, a sporting and cultural national body, unconnected to political violence.

Quasi-legal Fenian initiatives included much deeper engagement in the day-to-day issues of the rural poor, and the discrete extension of logistic support to those attempting to convince the House of Commons to legislate in a manner favourable to Ireland. The revolutionary underground, however, was very much alive and, due to its temporary derailment in 1867, more keenly attuned to the threats posed by infiltration and agents provocateurs. The necessity of maintaining a credible, versatile paramilitary challenge to Dublin Castle, while guarding against its well-resourced counter-measures, ultimately spawned the Invincibles.

As is comprehensively detailed in this volume, the Invincibles surfaced when the newly formed Irish National Land League was deemed by the IRB to require robust underpinning. Liaison between leading Fenians and the Irish Parliamentary Party, not least Charles Stewart Parnell, preceded the October 1879 foundation of the Land League. A de facto alliance was by no means a foregone conclusion. Agitation for far-reaching land reform, rather than preparations to achieve an independent republic, did not appeal to all IRB and CnG figures, but significant grassroots aid was nonetheless provided. To a much greater extent than previously experienced, Fenians in Ireland generated support for the Land League and engaged in agrarian activism under its banner.