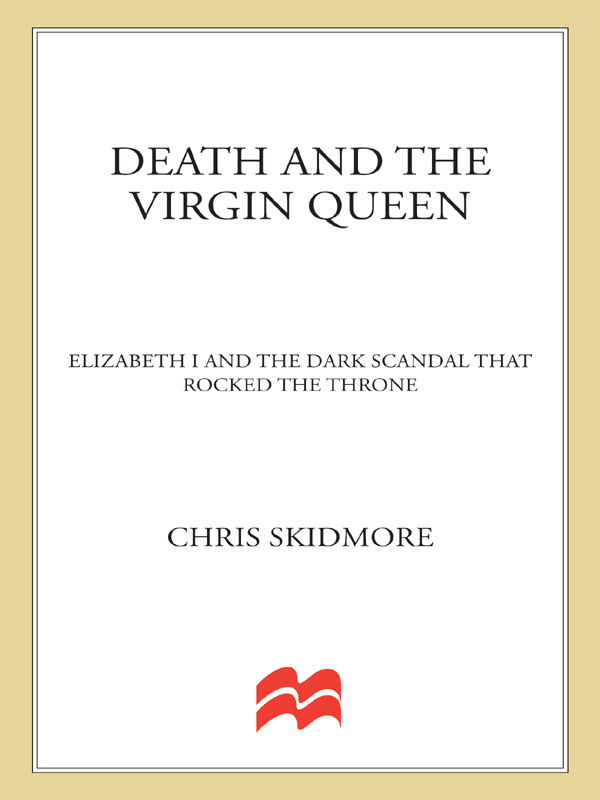

Chris Skidmore was born in Bristol in 1981. His first book, Edward VI: The Lost King of England , was published in 2007. He previously taught at Bristol University and is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. In 2010 he was elected as Member of Parliament for Kingswood.

To my mother, Elaine

Illustrations

Plate Section

Queen Elizabeth I, by Federico Zuccaro, c . 15571609, black and red chalk (The Trustees of the British Museum)

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, by Federico Zuccaro, c . 15571609, black and red chalk (The Trustees of the British Museum)

Elizabeth Is Procession Arriving at Nonsuch Palace, by Joris Hoefnagel, Flemish engraving (Private Collection/Bridgeman Art Library)

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, by or after Arnold van Brounckhorst, oil on panel, c . 1560s (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Elizabeth I, unknown artist, oil on panel, c . 1559 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

The Queen in her Litter, from The Progresses of Queen Elizabeth 1, ink on paper (Private Collection/Bridgeman Art Library)

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, c . 1560s, oil on panel (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection/Bridgeman Art Library)

Amy Dudley, by Lavinia Teerlinc, miniature (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection/Bridgeman Art Library)

Cumnor Place (courtesy of Edward Impey)

Staircase at Cumnor Place (The Trustees of the British Museum)

Eighteenth-century drawing of Cumnor Place, by Samuel Lysons, Magna Britannia , 1806

Photograph of the coroners report of into Amy Dudleys death (National Archives, Kew)

Queen Elizabeth receives Dutch ambassadors, gouache on card, Neue Galerie, Kassel, Germany (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel/Bridgeman Art Library)

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester, c . 1585, attributed to George Gower (Longleat House, Wiltshire/Bridgeman Art Library)

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, by Steven van der Meulen (Sothebys Picture Library)

La Volta, Penshurst Place (courtesy of Viscount de lIsle)

Text Illustrations

Contents

Acknowledgements

This book has taken far longer to write than I had expected, during which time I have accumulated a large number of debts. Foremost, I am extremely grateful to Alan Samson at Weidenfeld & Nicolson for his patience and commitment, and to the excellent editing skills of Bea Hemming, who has tirelessly guided this book through many versions. Penny Gardiner has also been a great critical friend, whose advice and ideas have been greatly appreciated.

I am also indebted to the remarkable generosity of several scholars, without whom the book would likely have remained unwritten. It was my former supervisor Dr Steven Gunn who first directed me to Amy Robsarts coroners report, while Dr Paul Cavill gave up his time to transcribe and translate the document. Dr Edward Impey has been extremely generous in providing me with copies of his thesis and drawings of Cumnor Place, while Gary Hill has been an enormous inspiration from the start of my research, showing me around the ruins of Cumnor Place and directing me to the archaeological investigations into the site of Amys tomb. I have greatly appreciated our conversations, and I look forward to the publication of his painstaking research on Amy, which will no doubt supplant my own. I am also extremely grateful for the expert medical advice given to me by Dr Ian Leslie and Professor Seth Love in discussing the nature of Amys injuries.

During my research, several archivists and libraries have made my work far easier than I imagined it would be. I would like to thank the staff of the National Archives and the British Library; Alison Day, the archivist at Berkshire Record Office, for providing me with copies of relevant wills; Jose Maria Burrieza Mateos at the Archivo General at Simancas for supplying me with copies from the archives there; Kate Harris at Longleat for sending photos of relevant documents, including Amys last letter; Robin Harcourt-Williams and Vicki Perry at Hatfield House for also providing copies of William Cecils papers; the staff at the Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge, for allowing me to transcribe Robert Dudleys letters there. I would also like to thank the kind generosity of the Marquess of Bath for permission to use Robert Dudleys private papers at Longleat; the Marquess of Salisbury for access and permission to quote from William Cecils private papers at Hatfield House; Magdalene College, Cambridge, for permitting me to reprint Robert Dudleys letters; the trustees of the British Library for permission to reprint several manuscript pages in their collection; and the National Archives for allowing me to publish Amys coroners report.

Finally, there are friends whom I would like to thank: Robin Ganguly and Fred Bosanquet put up with me while I was writing this book, as did Charlotte Leslie who also provided me with ideas and advice more than she probably realises. Michael Gove was extremely generous in allowing me a sabbatical from work to write the book. I would like to thank them all for their patience and understanding. My agent, Jonathan Pegg, has also been as ever a great source of encouragement and advice. Most of all, once again, I would like to thank my parents for their support, without which I would have struggled to complete this book. I could not have asked for more, especially from my mother, Elaine, and it is to her that I dedicate this book.

Chris Skidmore

Bitton, November 2009

A Note on Money

In 1560,1 (li) had the purchasing power of 209 in todays money. There were twelve shillings (s) in every 1, making them worth 17.40 today. A penny (d) was worth a twelfth of a shilling and its current value is around 1.45. This measure is based on the retail price index, designed to calculate the cost of everyday items such as food, drink and other basic necessities.

When attempting to give a relative value to salaries and large monetary transactions, an income of 50 in 1560 would be the equivalent of just over 140,000 in todays money.

These estimates are based on the calculations of Professors Lawrence H. Officer and Samuel H. Williamson, from their website measuringworth.com .

Prologue

As the summer of 1560 drew to a close, the queens progress returned to Windsor Castle. Throughout the usual sultry months of July and August, when the oppressive heat and stench made life in London unbearable, Elizabeth and her court made their annual journey through the Home Counties, stopping off on their winding route at royal hunting lodges and stately homes. Here the nobility reluctantly bore the cost of hosting the queen and a train which included not merely the queens gentlewomen but hundreds of attendants and servants, gentlemen and nobles, cooks and royal halberdiers, with nearly two and a half thousand packhorses carrying luggage, beds and provisions, packed away in four hundred carts trundling along their daily journey of around ten miles. The sight had onlookers at the roadsides staring in amazement.

Illustrations

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements