For Simon and all young Dubliners, in the hope of better days

Chapter 1  |

| A VICTORY BALL, A REGULAR LITTLE ARSENAL AND A MIDNIGHT VISIT TO DETECTIVE HEADQUARTERS |

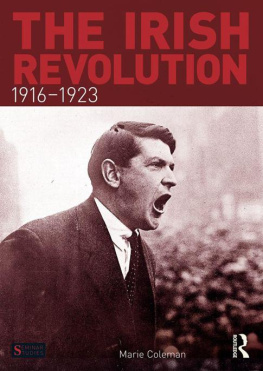

A Victory Ball at Dublin Castle ushered in the new year for 1919 with a fanfare by the trumpeters of King Edwards Horse Regiment. Such a scene has not been enjoyed since 1914, the Weekly Irish Times enthused. Nearly 1,200 guests attended the subscription dance for the British Red Cross, which was presided over by Isabelle Shortt, wife of the Chief Secretary for Ireland. While the main event was held in St Patricks Hall, the more discriminating dancers preferred the less crowded facilities of the Throne Room or the billiard room of the Red Cross hospital, which still occupied most of the State Apartments. Patients had decorated the rooms for the guests, and eight soldiers recovering from their wounds watched some distance away from the joys they were unable to share.

Among the social luminaries to survive the trauma of the war years was the perennial Lady Fingall, who organised the state lancers quadrilles for the older set. For the younger set there were foxtrots and the popular one-step and two-step tunes that occupied most of the programme, as well as numerous waltzes. After the singing of Auld Lang Syne to the accompaniment of the combined military bands there was spirited cheering and the taking of many flashlight photographs, which set everyone laughing and chattering on their way to supper. Subsequently the dancing was renewed with fresh vigour and continued into the early hours.

The Irish Times paid its usual attention to the gowns of the ladies. Most of the women, such as Lady Emily Campbell, wife of the Lord Chancellor and former unionist MP for Dublin University (essentially Trinity College), wore black in memory of close relatives killed in the war. An exception was Mrs Shortt, to whose executive ability the success of the ball was largely due. She wore a gown of mauve crepe de chine, although she had lost her only son in the defence of the British Empire. One of many constant reminders of the toll exacted from ascendancy families was the seemingly endless Roll of Honour column in the Irish Times each morning, listing those who had died of their wounds or who had been listed as missing in action and were now confirmed dead.

The other notable difference between the Victory Ball and similar social functions from the pre-war years was that there was no longer any flamboyant display of Irish fashions. If Irish gowns and accessories were worn at all, they were not flaunted.

In the dark, wintry Dublin of January 1919 there was not even the pretence of a shared future or identity of interest between the celebrants in Dublin Castle and the hostile citizens outside, who, a fortnight earlier, had voted overwhelmingly for Sinn Fin and independence. Two days after the Victory Ball, Dublin Corporation (as the city council was then called) held a special meeting requisitioned by fifty-eight members to offer the honorary freedom of the city to the president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson. They called on him to use your mighty influence in urging the Peace Congress to give a just judgement of Irelands cause and to arrive at a just settlement of her claim.

The following Sunday there were rallies in Dublin and Kingstown (Dn Laoghaire) and throughout the country to protest against the continued detention of almost two-thirds of the new Sinn Fin MPs in various Irish and British prisons. In Dublins own Mountjoy Prison, Sinn Fin and Irish Volunteer prisoners embarked on a hunger strike over being kept in the same appalling conditions as ordinary criminals.

On 2 January 1919 Dublin Corporation met to strike the rate (local property tax) for the new year; but the debate consisted primarily of attacks on the composition of the governments new advisory committee for rebuilding the Irish economy. The councillors argued, with some justification, that the committee was dominated by members of the Kildare Street Club and leading lights of the unionist establishment, such as the Marquis of Londonderry, the Earl of Granard, Lord Dunraven, Sir Henry Robinson (vice-president of the Local Government Board) and Eddie Saunderson, son of a former leader of the Unionist Party, now private secretary to the Lord Lieutenant, Field-Marshal Sir John French.

The proposed rate was a record 18s in the pound, to meet the soaring costs of running the city. War inflation still drove the economy, with wages chasing prices. The earnings of white-collar workers had increased between July 1914 and January 1919 by 60 per cent, those of skilled workers by between 120 and 140 per cent and those of labourers by as much as 210 per cent. Unfortunately, retail prices had risen by 240 per cent. The corporation had no control over prices, and the business community felt strongly that further pay demands by city employees should be firmly resisted, including a novel claim for a shorter working week without any cut in wages.

When traditional champions of the business community, such as Alderman David Quaid and the Sheriff, John McAvin, protested that the corporation was going from bad to worse they were told by nationalist colleagues that it was better to give the workers money for services rendered than endure a strike that would deprive the city of power and light. The increase was provisionally agreed, by 33 votes to 10.

The threat to power supplies did not arise only from industrial militancy. For the first quarter of 1919 Dublin Corporation often had less than two weeks reserves of coal. The January sales suffered from shops having to close early to conserve fuel and observe government restrictions on indoor lighting. The illusion that peacetime plenty was returning helped boost seasonal sales but was belied by shorter opening hours. Fanciful sketches of attractive women on the front pages of the newspapers, displaying fur coats with generous discounts of 25 per cent, could not hide the fact that the furs themselves were of seal and moleskin. On the other hand, in a salute to better times ahead, flexible corsets previously advertised as suitable for war work were now promoted as suitable for dancing.

On Tuesday 6 January thirty Sinn Fin MPs still at liberty met under the chairmanship of George Noble Plunkett (generally referred to as Count Plunkett after being made a Papal count in 1877), father of the executed 1916 leader Joseph Plunkett, in the Mansion House, Dublin, to demand the release of their colleagues. They agreed in principle to convene Dil ireann, the first national assembly in almost 120 years, and to invite all elected representatives of the Irish people to attend.

That evening there was a debate in the Abbey Theatre on the issue of Irish Federalism versus an Irish Republic between Captain Stephen Gwynn, former Irish Party MP for Galway, and P. S. OHegarty, a leading propagandist of advanced nationalism and member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Hopes were high that a still-embattled empire would have to concede independence quickly. Dublin Corporations quandary over how to contain wage demands without provoking a strike was as nothing compared with the dilemmas facing the British government. That same week more than seven thousand soldiers left their camp in Shoreham, Kent, and marched to Brighton to protest at delays in demobilisation, and members of the Army Service Corps drove lorries up and down Whitehall in London to demand a speedy return to civilian life. Further protests followed on Tuesday in London, Aldershot and Bristol.

Next page