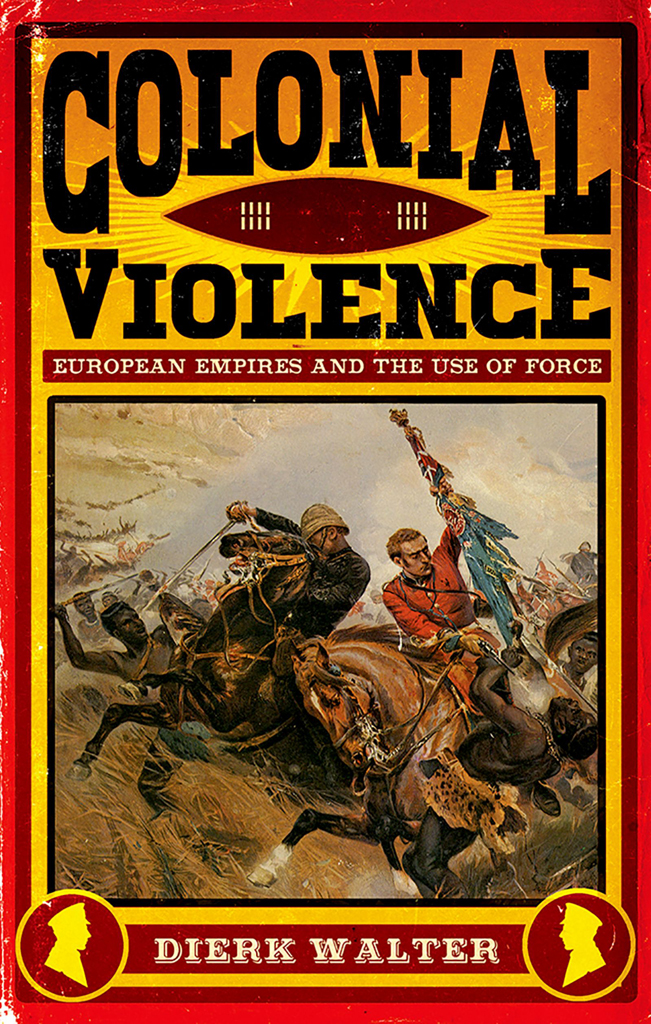

COLONIAL VIOLENCE

DIERK WALTER

Colonial Violence

European Empires and the Use of Force

Translated by

Peter Lewis

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Copyright Dierk Walter 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Dierk Walter.

Colonial Violence: European Empires and the Use of Force

ISBN: 9780190911522

CONTENTS

Afghanistan since 1999, Iraq since 2003, Mali since 2013the continuing military interventions of Western powers in the Third World in the opening decades of the twenty-first century now only make occasional headlines. In the interim, we have become used to Western troops being permanently stationed in Africa and Asia, while even the term war (long proscribed in some countries, notably Germany, on constitutional and historic grounds) is increasingly becoming commonplace to describe such armed deployments.

Yet recognition of this basic fact is at the same time intrinsically bound up with the idea of a far-reaching change in our whole conception of war. The peripheral conflicts of current times clearly have little in common with the traditional understanding of war in Western modernity, which is still wedded to the idea of symmetrical superpower conflict as epitomized by the world wars that were waged in the twentieth century. The armed forces of the USA and Western Europe, which for decades were equipped and trained for highly intensive mechanized warfare in the shadow of tactical nuclear weapons, continue to find themselves in a state of mental and organizational reorientation, given that the (often strongly politically driven) deployment of limited troop numbers in poorly developed regions lacking in state infrastructure represents a new and unfamiliar challenge for military elites whose mindset is still shaped by the image of the Cold War. Journalists, political scientists, soldiers and defence policy analysts are in little doubt that the peripheral interventions of the twenty-first century represent new wars.

And yet a historically informed assessment of these conflicts appears to suggest the opposite: the current military incursions by Western forces into Third World countries follow in a long tradition. In the characteristic determinants of warfare, in their external appearance and in their conflict logic they are remarkably similar to the armed conflicts between European powers and non-European societies that erupted from the start of European expansion throughout the world. The conquest of the Americas and the maritime expansion that took place in Asia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; the wars against the indigenous peoples of North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; the classic colonial wars during the age of imperialism; the major wars of decolonization after 1945, the hot wars of the Cold War fought out in the Third World: these all bear a striking family resemblance to present-day interventions, thus unmasking the concept of new wars as at best short-sighted, characterized by a fixation on the core European image of warfare in the twentieth century, and at worst as journalistic sensationalism.

There is a reason why this family resemblance has gone largely unnoticed. The boundaries drawn between eras in academic studies militate against viewing earlier conflicts, even those of the Early Modern period, and those of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries together in the round. The year 1945, which ushered in the Cold War and the process of decolonization, is such a key cut-off point for the world of today that most people find it hard to accept any continuities that transcend this break. Moreover, imperialism, colonies, colonial rule and colonial wars have meanwhile had such a bad press that current conflicts have to steer clear of any association with these older structures and precedents, if only on the grounds of legitimacy. Correspondingly, most informed contemporaries would doubtless concur that the humanitarian interventions and the War on Terror of recent decades have few if any parallels in the campaigns of colonial conquest and punitive expeditions conducted during the age of imperialism, if only because there are no longer any Western empires that are taking possession of overseas colonies. Even in de facto protectorates like Iraq or Afghanistan, Western nations have refrained from redrawing the map of the world in the manner of the late nineteenth century.

However, from the perspective of a longer-term history of the exercise of power and force in the modern world, such constitutional distinctions conceal certain fundamental structural continuities. One does not need to be a neo-Marxist to recognize that the world of the present continues to be shaped by the political, economic, military, legal, and cultural dominance of the principal Western powers. All in all, this is undoubtedly an imperial structure, a power relationship between strong and weak collectives, between politically, economically and culturally expanding and dominant core societies on the one hand, and on the other peripheral societies that are structurally dependent on the former. Military interventions in this context are in essence intended to guarantee the inclusion or re-inclusion of these peripheral societies into the global system and to enforce its rules (international law) and values (democracy, capitalism and liberalism). Whether colonies come into being in the process is not of any great analytical relevance here, especially since, in the overall history of European expansion, formal colonial rule only ever represented the shiny obverse of the imperial medallion, whose less impressive reverse consisted of the prolonged economic dominance of the West over large parts of the world, imposed through political and military means.

This perspective, which instead of the global caesuras of the twentieth century places structural continuities in the foreground, may not perhaps accord with the political consciousness of today and its need for legitimation, but certainly does reflect the current state of research into imperialism, which increasingly regards the entire modern era as a 500-year-long history of European expansion throughout the world. Whereas in earlier studies dramatic parts of this process, supposed concentrations, were singled out as (the age of) imperialism, in the last few decades, research carried out by Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher as well as Peter Cain and Anthony Hopkins has substantiated the thesis of continuity with earlier eras, at least in the case of British imperialism.