For Franoise Beucher

Copyright 1994 by Paddy Griffith

First published in paperback 1996. Reprinted 1998, 2000

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Set in Monotype Bembo

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Griffith, Paddy.

Battle tactics of the western front: the British Armys art of attack, 191618 / Paddy Griffith,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.258) and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-06663-0 (pbk.)

1. World War, 191418CampaignsWesten. 2. Tactics. 3. Strategy. I. Title.

D756.G75 1994

940.4144dc20

93-42656

CIP

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Contents

Competence and incompetence

The larger second half of the war

The nature of tactics

Lines, densities and timescales

The storm of steel

Tactics of the Old Contemptibles

The New Armies arrive

Rifles, bayonets and the cult of the bomb

The importance of careful preparation

The assault spearhead of the BEF

The formal Battles of 1917 and the chaotic battles of 1918

Flexible formations for mobile war

The mobilisation of invention

Bombs, smoke and gas

The struggle to control automatic fire

The rise of the light machine gun

The evolution of precision munitions

The shift from destructive to neutralising fire

The emergence of the deep battle

Cavalry and armour

Signals and command

Captain Partridge and the dissemination of doctrine

Training schools and other exhortations

List of Figures and Tables

Figures

(Notional) Comparison between the loss of trained tactical leaders and the need for them

Variants of the wave attack by the 9th Division, 191516

Platoon tactics, February 1917

Successive fragmentation of XVIII Corps in March 1918

Advances of the BEF in the Hundred Days, 1918

The flexibility of diamonds: the BEFs 1918 concept of a fluid infiltration attack

Schematic layout of BEF cable grid, as from late 1916

Armies in autumn 1916

Armies in autumn 1917

Armies in spring 1918

Armies in autumn 1918

Tables

Approximate number of divisional battles

Length of the British line in France

Effective combat performance of British infantry weapons

Organisation of motor machine gun brigades

British artillery weapons

Total British shell production per month

Proportion of shell types in selected creeping barrages

Speed of creeping barrages in some 9th Division attacks

Speed of some creeping barrages in the Hundred Days

Expenditure of artillery ammunition, by weeks

Yards of front per gun on first days of battle

Tanks committed to action during the Hundred Days

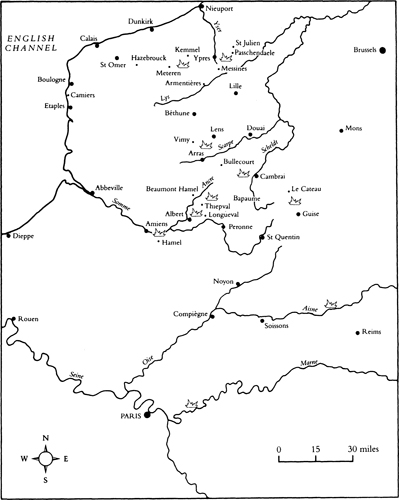

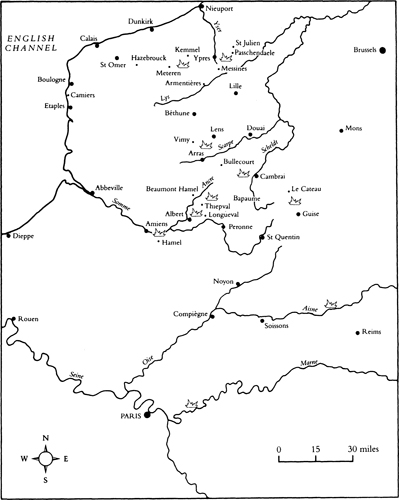

Some of the chief British sites on the Western Front

Preface

T he present book began life during a stimulating conversation with my friend and former colleague G. D. Sheffield, a War and Society historian who is best known to the wider world for his scholarship in Great War studies. This in turn recalled a series of pertinent thoughts on tactics that had been provided some years earlier by another scholarly observer of twentieth-century warfare, Andrew Grainger. In the autumn of 1990, therefore, I discovered that between them these two had somehow contrived to awaken an interest within me that I had for many years sworn seriously to abjure.

Throughout my life as a Briton and a military historian, the Western Front had always seemed to represent something of a blighted absolute. It was the British Armys biggest campaign ever, but apparently also its biggest disaster. Technically a victory, the war continued so indecisively and for so long that its commanders should surely shoulder a whole mountain of blame for their failure to modernise tactics all the alluring protestations of apologists notwithstanding. Merely to visit the Ypres Salient today, and to trace the fields no bigger than football pitches where entire brigade attacks were halted almost before they had begun, is to suffer a cold depression of the soul.

In historiographical terms the Great War also seemed to be something of a disaster area, since it has become the favoured playground of popular authors who love to dwell on the horrors and the incompetence without stopping to make a proper military analysis. This is annoying in itself; but for me it has had the additional effect of helping turn the academic world away from true military history (see Appendix 1). During my working life I have encountered considerable resistance to serious military study among the politically correct members of the university, and it has often been the Great War which they have used as the reference point for their prejudices.

All these unpromising features of Great War historiography conspired together for many years to warn me away from the subject, and I tried to confine my studies to the conflicts that came either before 1914 or after 1918. However, I have now at last come to swallow my reservations and have attempted to give the Great War the long hard gaze that it had previously tried so hard to avertand I have been fascinated to discover just how richly it has rewarded me for my effort.

As a first step I saw some illuminating parallels and contrasts with the American Civil War, which was a conflict that I had studied in the past (see Appendix 2). Beyond those, it came as something of a surprise to find that much Great War historiography tended to be dismissive of the many technical achievements of the infantry, as opposed to its awesome and oft-repeated ability to suffer and endure. It is therefore around this subject that I have tried to construct the present volume. While I must certainly apologise that it does not look in very great detail into the actions of the artillery, the tanks or the air forces on the Western Front, I would respectfully point out that each of these branches has received many excellent modern treatments, and each even still maintains its own active network of propagandists. I hasten to add that I have not yet met or read a single unfair modern propagandist for any of them; but I suspect that there does nevertheless remain a deep structural unfairness in the literature, insofar as many of the other branches that were essential to the Great War fighting have now apparently fallen completely silent. The Machine Gun Corps is the most obvious example, since it was disbanded immediately after the armistice and has left no successor apart from a fading Old Comrades association. By the same token there is no longer an identifiable trench-mortar lobby or a hand-grenade lobby and both the gas debate and the signals debate have long ago moved forward to very much higher manifestations of their respective black arts. But above all it seems to be the infantry itself, which so horrifically bore so much more than the lions share of the war, that has most seriously been denied a proper account of its tactical methods in modern times. In the present book I therefore hope to offer something of a corrective to this trend.

Next page