Table of Contents

For Tim

ACCLAIM FOR JILL LEPORES

New York Burning

Winner of the Anisfield Wolf Book Awardand the New York City Book Award

Engaging.... [Lepore] has re-created a little-known but significant incident in Colonial history, skillfully unraveling the threads of conspiracies.

The Boston Globe

A reconstruction at once factually rigorous and brilliantly imaginative.

The New York Sun

Remarkable.... Lepore mixes in legal, political, religious and literary information.... A tour de force.

The Winston-Salem Journal

Riveting.... [Lepore] draws a splendid portrait of the struggles, prejudices and triumphs of a very young New York City in which fully one in five inhabitants was enslaved.... First-rate social history.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Lepore... has chosen an exquisite puzzle for a historian. There is a load of colorful material detailing the events of 1741, but all of it is from one side.... The challenge is to tease out what isnt here, to give voice to those whom history has rendered mute. She does this with great skill.

The Nation

[Lepore] brings this terrifying period vividly to life.... A gripping read that shows how quickly fear spread through a city resting upon a terrible imbalance.

The Star-Ledger (Newark)

A work of rigorous scholarship, but... also a pleasure to read, delivering the thrills of a complex historical mystery novel.... A fascinating take on a dark chapter in U.S. colonial history.

Time Out New York

Meticulous but accessible work of historical scholarship.... A stellar performance.

Booklist (starred review)

Remarkable... intriguing.... Lepore is truly a master of her art and I sincerely look forward to her next efforts, for our understanding of complex issues will be all the clearer because she knows her field so well.

John Davis, The Decatur Daily

Liberty is to live upon ones own Terms; Slavery is to live at the meer Mercy of another; and a Life of Slavery is to those who can bear it, a continual State of Uncertainty and Wretchedness, often an Apprehension of Violence, and often the lingering Dread of a violent Death.

John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon,

Catos Letters, reprinted in Zengers New-York

Weekly Journal, September 15, 1735

Let by My specious Name no Tyrants rise, And cry, while they enslave, they civilize! Know LIBERTY and I are still the same, Congenial!ever mingling Flame with Flame!

Richard Savage, Of Public Spirit in Regard

to Public Works, 1737

I know not which is the more astonishing, the extreme Folly, or the Wickedness of so base and shocking a Conspiracy; for as to any View of Liberty or Government you could propose to yourselves, upon the Success of burning the City, robbing, butchering, and destroying the Inhabitants; what could it be expected to end in... but your own Destruction?

Daniel Horsmanden, sentencing Quack and Cuffee

to be burned at the stake, May 29, 1741

I am a dead man.

Adam, from his jail cell, June 27, 1741

Preface

"LIBEERTY and SLAVERY! how amiable is one! how odious and abominable the other! wrote James Alexander in the pages of the New-York Weekly Journal in 1733. When Alexander championed liberty and condemned slavery, he meant the liberty of the press and the slavery of tyranny. No Nation Antient or Modern ever lost the Liberty of freely Speaking, Writing, or Publishing their Sentiments, he warned, but forthwith lost their Liberty in general and became Slaves.1 By slaves, Alexander meant a nation ruled by a despot; he did not mean the two thousand men, women, and children who toiled as human chattel in the bustling city of eighteenth-century Manhattan, a number that included not only the five people who lived in Alexanders own elegant house but also the one black man who had escaped from its attic, carrying a pass he had penned himself, in an act of forgery that defined, better than anything Alexander could put to paper, the liberty of freely writing.

Political liberty was the most cherished blessing in the British realm, and political slavery its most dreaded specter. Rule, Britannia, rule the waves; / Britons never will be slaves, wrote an English poet in 1740, in lines that became the empires anthem. But throughout that empire, and especially in its American colonies, dark-skinned people lived under worse than the slavery of tyranny; they lived in the slavery of human bondage. In the colonies, liberty and slavery tripped off tongues, and nearly slipped into meaninglessness. Though Liberty and Slavery are words which incessantly vibrate on the ears of the Public, wrote one colonist, yet we have few terms in the English Vocabulary so generally misunderstood.2 Everywhere, liberty was passionately celebrated, and slavery just as passionately condemned, by men like James Alexander, Americans who owned Africans.

That calls for liberty came from a world of slavery has been named the central paradox of American history. Eighteenth-century observers did not fail to remark upon it. How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes? Samuel Johnson famously complained in 1775, in a reply to American revolutionaries protest of parliamentary taxation. Nor have historians quieted their astonishment, and rightly so. The paradox is American, and it behooves Americans to understand it if they would understand themselves, wrote Edmund Morgan in 1975.3 Three decades and Thomas Jeffersons twenty-three chromosomes later, Americans are now quite aware of the American paradox, but it remains, somehow, impossible to understand. That abject bondage contributed to the creation of the worlds first modern democracy, however true and even self-evident, is, finally, so painful a truth as to be nearly unfathomable.

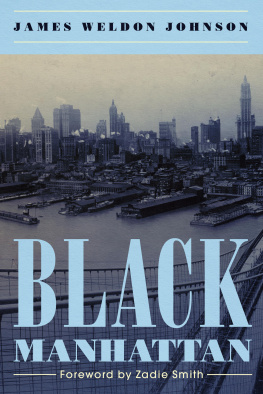

This book tells the story of how one kind of slavery made another kind of liberty possible in eighteenth-century New York, a place whose slave past has long been buried. It was a beautiful city, a crisscross of crooked cobblestone streets boasting both grand and petty charms: a grassy park at the Bowling Green, the stone arches at City Hall, beech trees shading Broadway like so many parasols, and, off rocky beaches, the best oysters anywhere. I found it extremely pleasant to walk the town, one visitor wrote in 1748, for it seemed like a garden.4 But on this granite island poking out like a sharp tooth between the Hudson and the East rivers, one in five inhabitants was enslaved, making Manhattan second only to Charleston, South Carolina, in a wretched calculus of urban unfreedom.

New York was a slave city. Its most infamous episode is hardly known today: over a few short weeks in 1741, ten fires blazed across the city. Nearly two hundred slaves were suspected of conspiring to burn every building and murder every white. Tried and convicted before the colonys Supreme Court, thirteen black men were burned at the stake. Seventeen more were hanged, two of their dead bodies chained to posts not far from the Negroes Burial Ground, left to bloat and rot. One jailed man cut his own throat. Another eighty-four men and women were sold into yet more miserable, bone-crushing slavery in the Caribbean. Two white men and two white women, the alleged ringleaders, were hanged, one of them in chains; seven more white men were pardoned on condition that they never set foot in New York again.

Next page