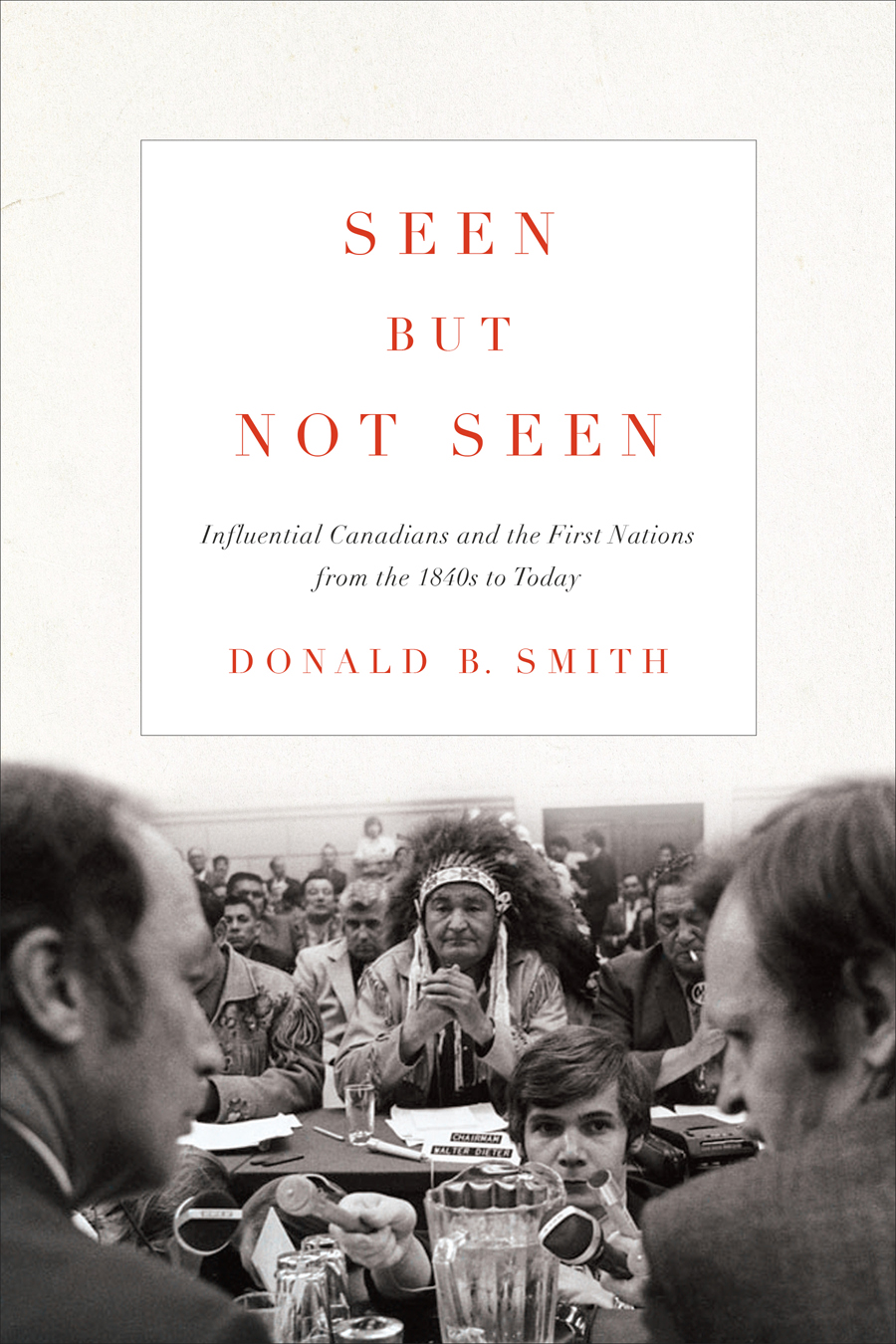

On 25 June 1969 the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau tabled in the House of Commons the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian policy, popularly called The White Paper (in government, the term white paper is applied to policy proposals). If passed by Parliament, the new legislation would end the unique legal rights of status Indians. Reserves and the historic Indian treaties, as well as the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development itself, would disappear. Indigenous protest against the policy initiative arose immediately. Provincial and territorial First Nations political associations across Canada joined the National Indian Brotherhood (NIB; founded in 1968 and reorganized in 1982 as the Assembly of First Nations) to oppose it. Walter Deiter, a former chief of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians and the NIBs founding president, led the fight against the attempt to end the special status of the First Nations.

On 4 June 1970 a phalanx of western chiefs, some dressed in traditional regalia, stood face to face with the prime minister and his full cabinet in the cavernous Railway Committee Room of the Parliament Buildings. Indian Association of Alberta (IAA) members Chiefs John Snow and Adam Soloway handed the position paper originally prepared by the IAA entitled Citizens Plus but popularly known as The Red Paper to the prime minister. Then Harold Cardinal, IAA President, spoke on the significance of treaty and Aboriginal rights. In response to strong First Nations protests against the assimilationist White Paper, the federal government formally retracted it in 1971.

Rudy Platiel, a retired Toronto Globe and Mail reporter, witnessed the Red Papers submission. Half a century later, he recalled: In 1970 I was assigned by The Globe and Mail to travel for a year across Canada to write about the situation of Indigenous people then called Indians. Despite the now continued existence of systemic racism, the march of Indigenous rights and their reality today is light years beyond anything I actually thought possible back then. This progress gives hope that despite our human flaws and occasional cruelty, as a nation we may one day yet reach a new dawn of acceptance and cooperation between two societies that at times seems so tantalizingly far beyond us today. There is indeed hope.

SEEN BUT NOT SEEN

Influential Canadians and the First Nations from the 1840s to Today

DONALD B. SMITH

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS

Toronto Buffalo London

University of Toronto Press 2021

Toronto Buffalo London

utorontopress.com

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-4426-4998-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-4426-2212-8 (ePUB)

ISBN 978-1-4426-2770-3 (paper) ISBN 978-1-4426-2211-1 (PDF)

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Seen but not seen : influential Canadians and the First Nations from

the 1840s to today / Donald B. Smith.

Names: Smith, Donald B., author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 2020034644X | Canadiana (ebook)

20200346539 | ISBN 9781442649989 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781442627703

(softcover) | ISBN 9781442622128 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781442622111 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Indigenous peoples Canada Public opinion. | LCSH:

Canada Ethnic relations. | LCSH: Canada Race relations. | LCSH:

Indigenous peoples Canada Social conditions.

Classification: LCC E98.P99 S65 2021 | DDC 305.897/071 dc23

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario.

Dedicated to the memory of John F. Leslie (19452017), historian, former manager of the Claims and Historical Research Centre at Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, and good friend for over thirty years.

Prologue

Before reading a book it is desirable and quickens interest to know something with regard to the author.

A.C. Rutherford, foreword to The Law Marches West (1939)

In the mid-1960s, as Canada approached its memorable Centennial year, most non-Indigenous Canadians harboured a long-established blindness to the Indigenous peoples in this country. I was one of them. Their history and contemporary living conditions remained unknown, a closed book. Yet, in these same years, the Indigenous peoples were on the verge of returning to the top of the public agenda for the first time since the North-West Resistance of 1885. Although I did not know it at the time, of course, two experiences in 1966 directed me towards a lifelong study of how non-Indigenous Canadians viewed Indians, as the First Nations used to be known. A January student conference at the University of Toronto, and a summer job on a railway gang in Western Canada, awakened me to Indigenous Canada. My journey visiting archives, reading constantly about Indigenous Canada, and travelling to First Nations communities seriously began half a century ago in my year at the Universit Laval in Quebec City.

I was born in Toronto in 1946 and grew up in Oakville, located halfway between the cities of Hamilton and Toronto. During my boyhood I cannot recall a single reference in public or high school to the Mississauga First Nations, Ojibwe-speakers who call themselves, Anishinabe (meaning in English, human being), or in its plural form, Anishinabeg. I do not remember meeting anyone in Oakville who self-identified as Indian. Indigenous people did not enter into the conversation. First Nations were not mentioned in the newspapers.

Cowboy movies and adventure films, such as those based on the American Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, frequently appeared in our two local movie theatres. One film on a North American Indian theme made a lasting impression because it portrayed the First Nations positively, without negative stereotyping. The Light in the Forest came out in 1958, the year before I entered high school. I read the 1953 historical novel by Conrad Richler, on which the film is based, some years later: After a 1764 peace treaty between the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) and the British, the First Nations promised to return all the settlers children taken in border skirmishes. A young man, adopted and renamed by the Delaware at the age of four, and raised by them for over a decade in the Ohio country, must now return against his will to his settler family in Pennsylvania, despite his wish to retain the language and rich culture of the Delaware that he now called his own.