Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Dedicated to the memory

of my brother

James Fairbanks Randall

United States Merchant Marine Academy

Class of 1978

The people of America had been educated in an habitual affection for England as their mother country, and while they thought her a kind and tender parent no affection could be more sincere. But when Americans discovered that the mother country was willing, like Lady Macbeth, to dash their brains out, it is no wonder if their filial affections ceased, and were changed into indignation and horror.

John Adams to Henry Niles, February 13, 1818

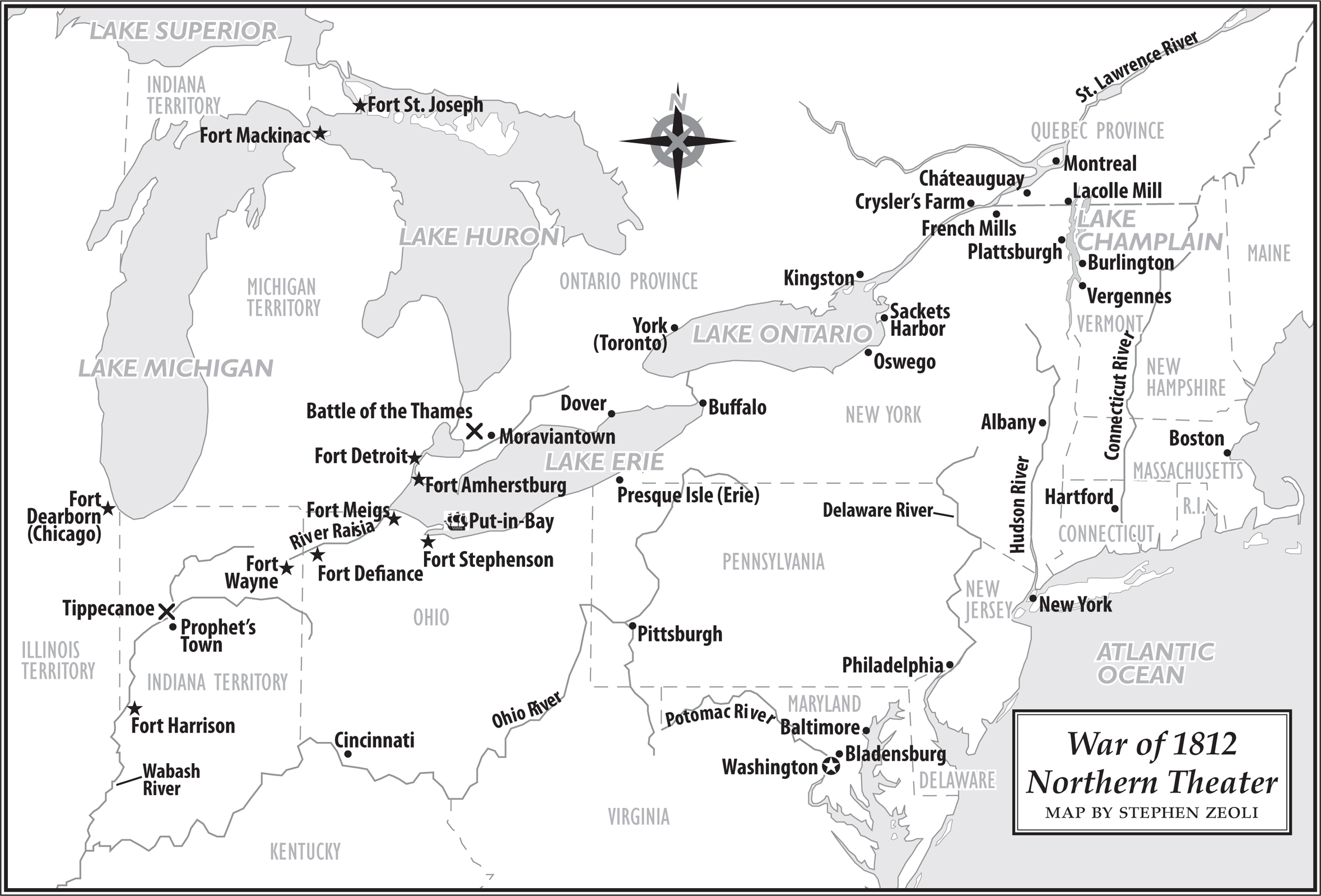

On April 25, 1806, three British men-of-war, Leander, Cambrian and Driver , were patrolling the entrance to New York harbor. All day, the sixty-gun frigate Leander had stopped every American ship, first lobbing a cannonball across its bow, the signal to heave to, be boarded and be searched for deserters from the Royal Navy and contraband from Britains enemy, France. Toward evening, the Delaware coastal schooner Richard, hauling produce to market, was only a quarter mile offshore. Two eighteen-pound cannonballs suddenly erupted from Leander , one cutting across Richard s bow, the other arcing overhead. Immediately Richard hove to, waiting for the British boarding party. But then a third projectile, skipping along the surface, crashed through the schooners taff rail, driving a large splinter through the neck of the helmsman John Pierce, decapitating him.

Pierces brother somehow managed to steer the schooner to the city docks in lower Manhattan. As he carried his brothers headless body through the streets, an angry crowd gathered. They had watched helplessly as British boarding parties, in an illegal peacetime blockade, seized American vessels before sailing them off to Halifax to be condemned by a British Admiralty court and auctioned off, the proceeds divided among Leander s captain and crew. A crowd of volunteers commandeered two British pilot vessels anchored at the wharf, overtook three British supply boats and forced them back to port, unloading their cargoes into carts for distribution among the citys poorhouses.

In front of the Tontine Coffee House, New Yorks incipient stock exchange, Pierces corpse remained on display during days of rioting. Britains consul-general hid in his house as a mob hurled stones through his windows. At Hardys waterfront tavern, merchants blamed President Thomas Jefferson for failing to resist years of British interference with Americas commerce. Like many Americans, they also blamed Jefferson for refusing to maintain a proper navy to protect Americas burgeoning maritime trade. Irate citizens also organized a city militia. The citys Common Council ordered Pierces burial at public expense and, as American ships in the harbor flew their flags at half mast, as a body led thousands to the interment to honor the seaman whose death had brought to a head years of fruitless protests against Britains attempts to stifle American trade.

When an express rider reached Washington City with Mayor DeWitt Clintons dispatches, Jefferson ordered the Leander and her sister ships to immediately & without any delay depart from the harbours & waters of the U.S. Even though the United States had won the Revolutionary War a generation earlier, Jefferson could do nothing now beyond issuing an empty decree that all British ships must leave American waters. After a hastily summoned New York grand jury indicted Leander s captain, Henry Whitby for murder, Jefferson decreed that if Whitby were ever found again in American territory, he was to be arrested and returned to New York to face the charge. If British ships ignored Jeffersons executive order and continued to come into American waters, Americans were forbidden to pilot them into ports, sell them provisions or provide them with fresh water or supplies of any kind. Jefferson called the stationing of British warships off Sandy Hook an atrocious violation of our territorial rights.

Jefferson must have known it was impossible to enforce his executive order. He had drastically downsized the navy, ordering its half dozen frigates into dry dock and replacing them with what naval officers called a mosquito navy of shallow-draft, poorly armed gunboats useful only close to shore.

Like fellow veterans of the Tripoli Wars, Navy commodore William Bainbridge fumed at this latest affront. How long must we bear these violations of our National honor, property, and loss of our fellow Citizens, he wrote to Captain Edward Preble. O Lord! Grant us a more honorable Peace or a sanguinary war!

All along the Atlantic seaboard, as news spread of the latest British provocation, newspaper editors trumpeted calls for war. DeWitt Clinton later wrote, I well remember the sensation excited by the murder of Pierce. It was a glow of patriotic fire that pervaded the whole community from Georgia to Maine it was felt like an electrical shock.

The Leander incident and the firestorm of anti-British resentment it ignited followed a quarter century of flare-ups in the struggle for the United States economic independence from Britain and its survival as a sovereign nation. What neither Jefferson nor any other of Americas founding generation could divine was that, even after the British imperial crisis that began with protests over illegal searches and seizures in Boston in 1761 and led to American military victory in 1783, what is commonly called the American Revolution constituted only the first phase of a far more protracted ordeal to achieve true independence. The Treaty of Paris of 1783 only halted the overt conflict of the Revolutionary War and granted political autonomy, but it did not guarantee American economic independence and agency. For fully three more contentious decades that led to another warthe War of 1812Britain continued to deny the United States sovereignty.

The second phase of the half-century-long struggle combined a domestic ideological crisis over American identity with unrelenting and ever-intensifying attempts by the British to stifle American trade and to starve her former colonies. From 1783 until combat resumed in 1812, the United States weak central government and a military enfeebled by Jeffersonian political purges rendered the young nations chance of survival dubious.

Ignoring their military failure in the Revolutionary War and the consequent treaty of peace, the British Parliament ratcheted up efforts to eliminate competition, first by re-invoking the colonial-era Navigation Act of 1756, requiring that all goods transported between British possessions or to and from England must be carried on British shipsEnglish goods in English bottoms. Banning long-existing trade between New England and its Canadian neighbor, the Navigation Act also barred long-flourishing commercial ties with British Caribbean colonies. Moreover, Britain insisted that its treaty allies, Spain and Portugal, embargo American trade and forbid trade with any of their three colonies. Britain also prohibited vital exports from England to the United States, including sheep, wool and woolens. All the while, in violation of the peace treaty, Britain refused to remove its troops from fortified trading posts around the Great Lakes and along the Canadian-American frontier. Throughout this perilous half century, the underlying cause of contention was Americas right to free trade.