The Social History of Agriculture

The Social History of Agriculture

From the Origins to the Current Crisis

Christopher Isett and Stephen Miller

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of

The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

https://rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB,

United Kingdom

Copyright 2017 by Rowman & Littlefield

All maps created by Grace Johnson and Jeff Kropelnicki

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Isett, Christopher Mills, author. | Miller, Stephen, 1968 author.

Title: The social history of agriculture : from the origins to the current crisis / Christopher Isett and Stephen Miller.

Description: Lanham, Maryland : Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031934 (print) | LCCN 2016034390 (ebook) | ISBN 9781442209664 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781442209671 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781442209688 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: AgricultureHistoryCase studies. | AgricultureSocial aspectsHistoryCase studies.

Classification: LCC S419 .I78 2016 (print) | LCC S419 (ebook) | DDC 630dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031934

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For our children: Joaquim, Sebastian, and Isabella

Maps

Africa

Eurasia

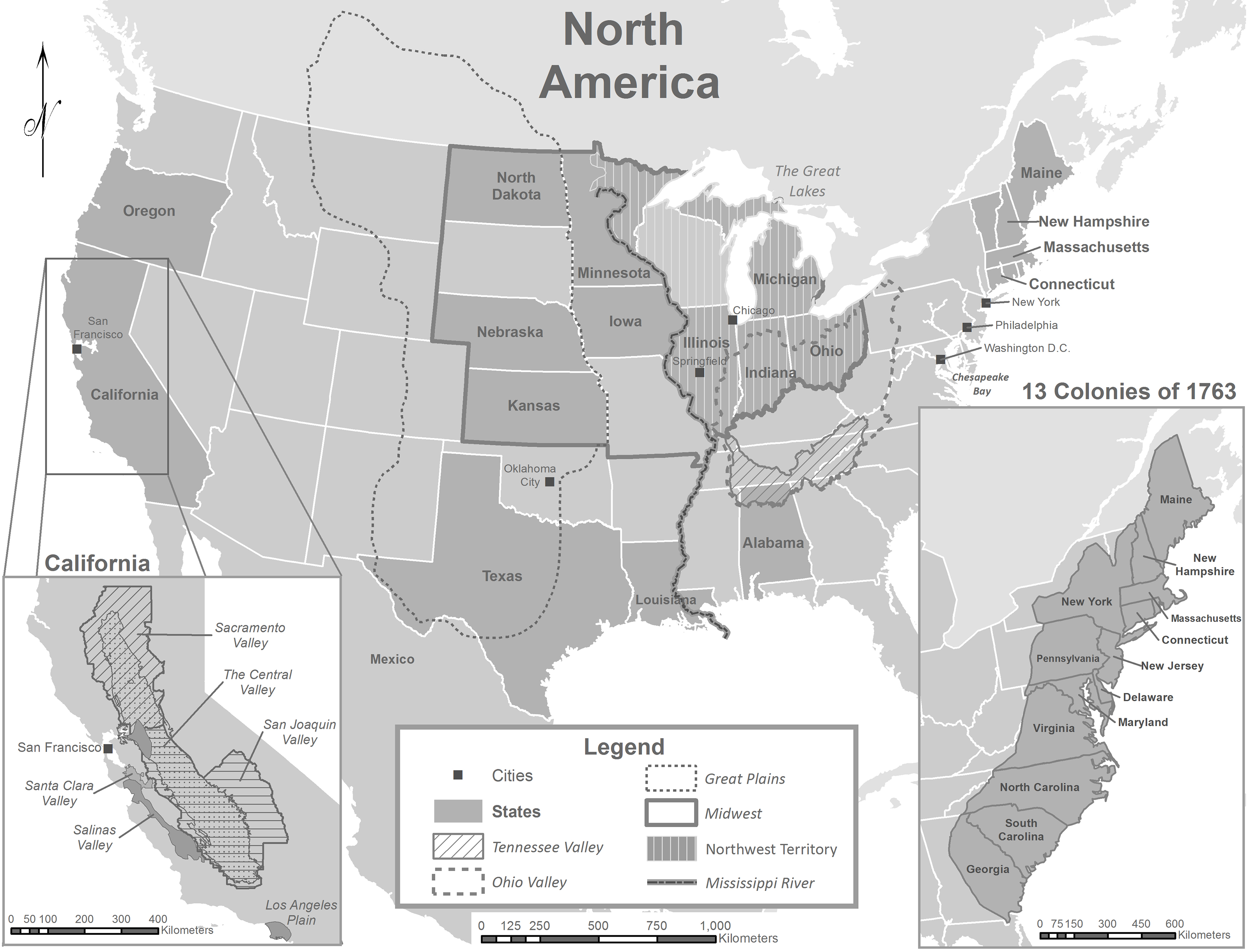

North America

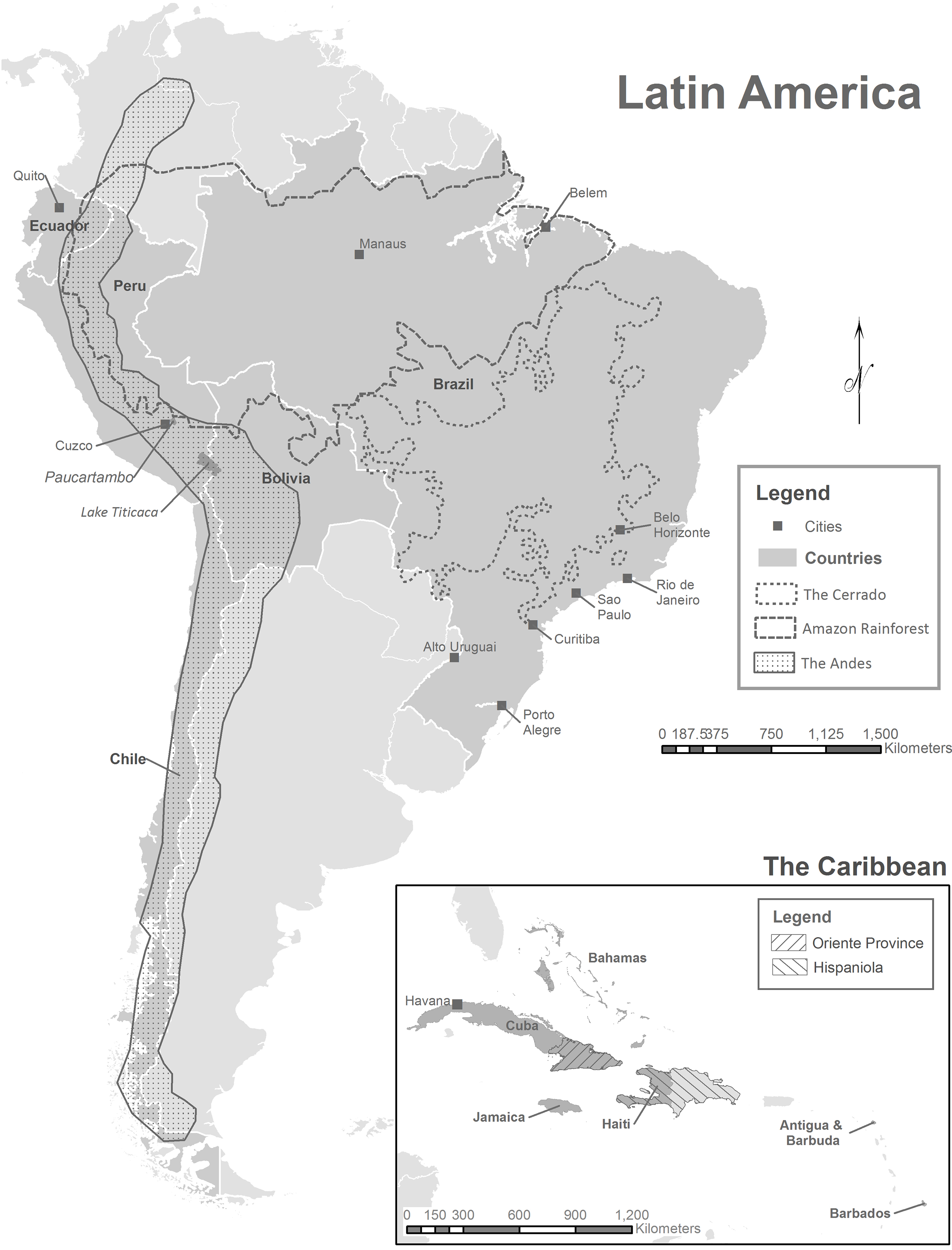

Latin America and the Caribbean

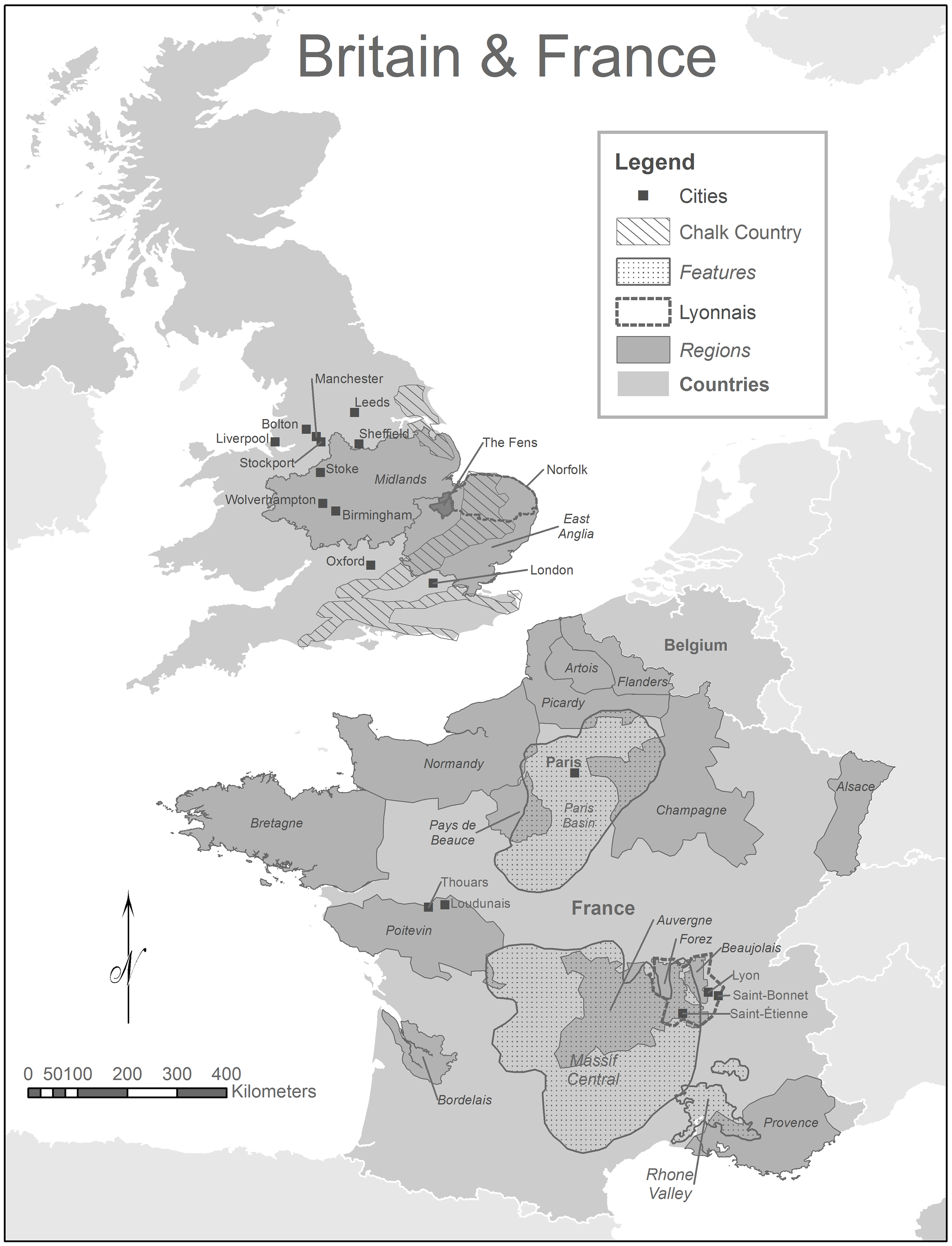

Britain and France

Acknowledgments

We have accumulated many debts along the way and are gratified to acknowledge those here. We begin by thanking and recognizing the importance of Robert Brenner and his work. We both took his graduate seminar at UCLA in the 1990s and our historical understanding has been shaped by his theoretical interventions ever since. Numerous experts have read and provided helpful comments. We thank the three anonymous reviewers for Rowman & Littlefield, each of whom made the book better. In addition, David Roediger read and provided feedback on early drafts of chapters 5 and 6 and Katharine Gerbner did the same for chapter 5. Spencer Dimmock gave crucial advice on chapters 1 and 3. Matthew Sommer read and discussed chapter 4. Charles Post provided excellent advice on many aspects of the book and did an expert critical reading of chapter 6.

Colleagues at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of Minnesota, and other universities and colleges pointed us in the direction of texts in translation and scholarly works outside our own expertise, and some met to discuss elements of the book. These include Ellen Amster, Venus Bivar, Sarah Chambers, Michael Vann, Vinayak Chaturvedi, Vivek Chibber, Mark Overton, Adam Guerin, Eva von Dassow, Preston Perluss, Brian Steele, Adam Hochschild, Andrew Keitt, John Van Sant, George Liber, Douglas Frey, Chris Kyle, Robert Jefferson, Zephyr Frank, Bruce Campbell, Andrew Gallia, David Miller, and Rus Menard.

We would like to thank Paul Cheney for providing the opportunity to present ideas for central parts of the book to faculty and graduate students at the Modern France and Social History Workshop of the University of Chicago and Patrick OBrien and Kent Deng for the chance to present the discussion of Tokugawa Japan in the Department of History at the London School of Economics.

Students in graduate seminars at the University of Minnesota and the University of Alabama at Birmingham read and discussed with us crucial books and articles that shaped our interpretations of agricultural societies in different regions and epochs. The staff at Sterne Library of the University of Alabama at Birmingham provided expert assistance in locating contemporary accounts (primary sources) of farming. We would also like to thank our students Tyler Boesch and Samuel Jane-Akson, who read and gave us invaluable feedback on the clarity of our argument.

Finally, we would like to express our appreciation for Susan McEachern, Alden Perkins, and Rebeccah Shumaker. Rebeccah and Alden guided the manuscript to print with great patience and even greater speed. Susan, as a longtime champion of the book, provided advice and sound criticism that markedly improved its quality. Of course, all errors of fact or omission remain our own.

Introduction

The association of civilization with settled agriculture is old. It exists in our history books but also in our language. Our word culture comes to us from the Latin colere, meaning to tend, to cultivate, or to husband. The agricultural sense is materialized in the cognate coulter, which is the blade of a plowshare. As the literary critic Terry Eagleton notes, We derive our word for the finest human activities from labour and agriculture. We believe that the etymological link between cultureand the society that produces itand farming is apposite.

We have titled this book The Social History of Agriculture because of our conviction that farmingindeed, all economically productive activityis a reflection of the society in which it is conducted, not the other way around. To put it another way, we argue that peoples choices of what to grow, the technologies to use, and the labor regime to employ are shaped by their societies.

Going further, we maintain that some social arrangements are more important than others in shaping economic means and goals. We emphasize the political and legal arrangements that emerge from the negotiations and conflicts between those who toil and those who receive the surplus, profit, or interest. These arrangements are necessarily the outcome of the history of a place and people and of the antagonisms between the major classes.

In this regard, we maintain that people are born into a world of already formed class relationships and that their capacity to achieve the social solidarities needed to reshape those relationships is continuously undermined insofar as they continue to live and work as disaggregated individuals, families, or communities. It follows that rather than change these relationships people on the whole make their way in the world as it is given to them, pursuing avenues that best allow them to get ahead within limits imposed by their societys class arrangements.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.