Contents

Guide

Also by Olivia Laing

To the River

The Trip to Echo Spring

The Lonely City

Crudo

Funny Weather

OLIVIA LAING

Everybody

A Book About Freedom

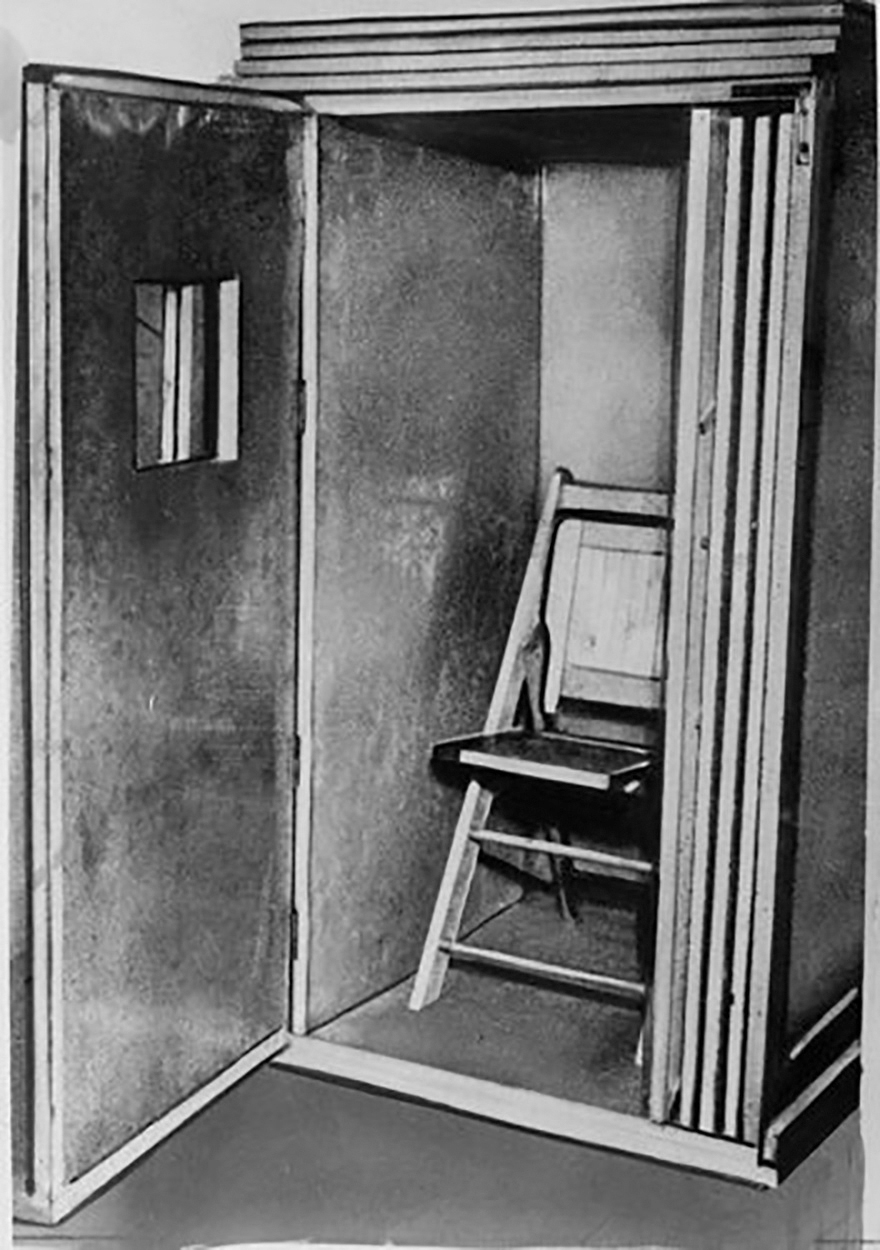

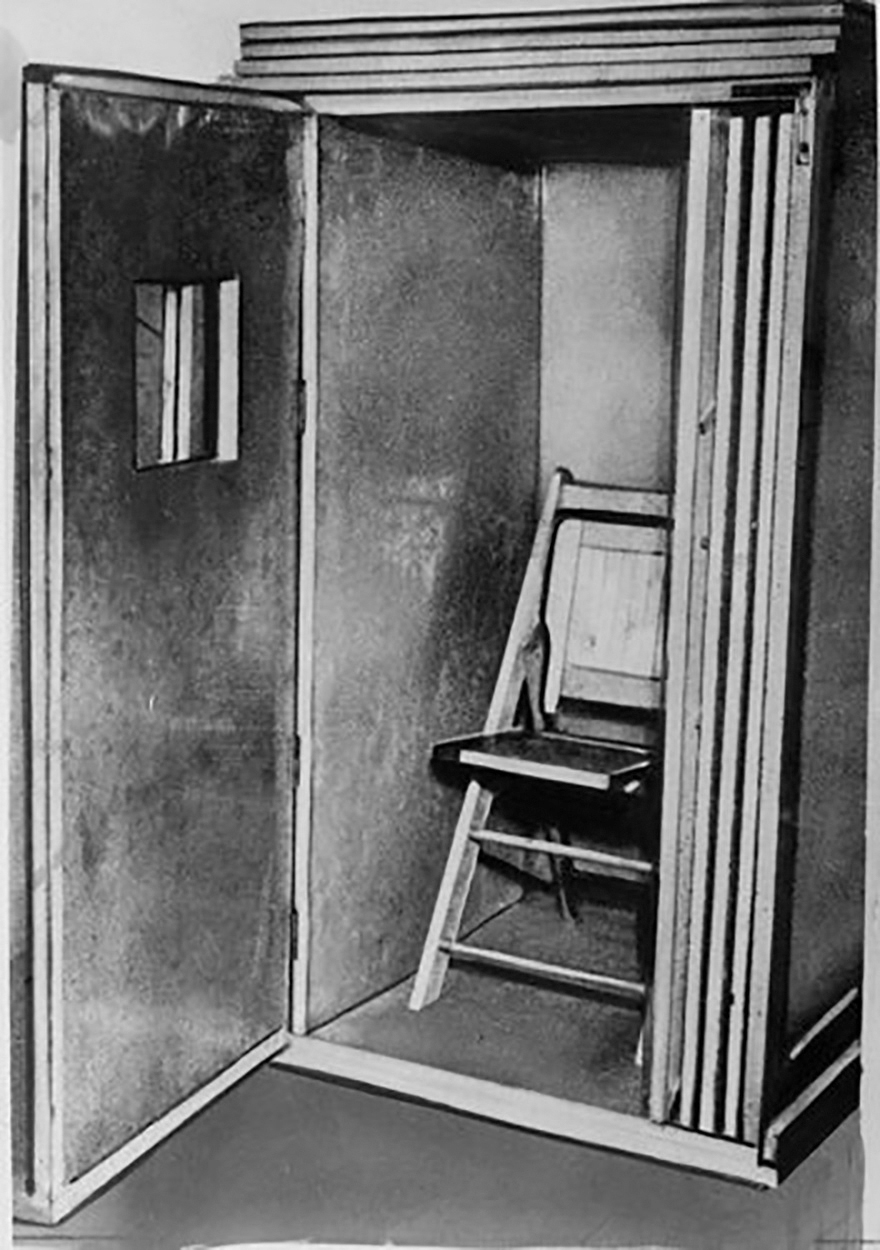

Image credit: Orgone accumulator (Topfoto)

Copyright 2021 by Olivia Laing

First American Edition 2021

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at or 800-233-4830

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Laing, Olivia, author.

Title: Everybody : a book about freedom / Olivia Laing.

Description: First American edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021000768 | ISBN 9780393608779 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780393608786 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Human bodySocial aspects. | Body image. | Human rights movements. | Freedom.

Classification: LCC HM636 .L44 2021 | DDC 323dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021000768

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

For Rebecca and PJ,

with love and gratitude

I dont want a body anymore. Fuck the body.

Ryan Trecartin, Sibling Topics

In my life politics dont disappear but take place in my body.

Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School

May we not say there is probably some sort of Transmutation of essences continually effected and effectible in the human frame?

Edward Carpenter, Loves Coming of Age

My life held precariously in the seeing/hands of others

Frank OHara, Poem

Contents

This is a book about bodies in peril and bodies as a force for change. I started it during the refugee crisis of 2015, and finished it just as the first cases of Covid-19 were being reported. The new plague has revealed the frightening extent of our physical vulnerability, but the global Black Lives Matter uprisings of the past year prove that the long struggle for freedom isnt over yet.

I N THE FINAL YEAR of the twentieth century, I saw an advert in a herbal pharmacy in Brighton. It was pink, with a hand-drawn border of looping hearts, and it made the bold claim that all symptoms, from headaches and colds to anger and depression, were caused by stuck energy from past traumas, which could be loosened and induced to move again by way of body psychotherapy. I knew this was a controversial statement, to say the least, but the idea of the body as a storage unit for emotional distress excited me. Id had a strong sense since childhood that I was holding something, that Id locked myself around a mysterious unhappiness, the precise cause of which I didnt understand. I was so rigid and stiff I flinched when anyone touched me, like a mousetrap going off. Something was stuck and I wanted, nervously, to work it free.

The therapist, Anna, practised in a small, soupy room at the top of her house. There was a professional-looking massage bed in the corner, but the overwhelming impression was of slightly grimy domesticity. Frilly cushions proliferated. My chair faced a bookcase crammed with charity-shop dolls and toys, awaiting their casting into Gestalt pantomimes. Sometimes Anna would take a grinning monkey and clutch it to her chest, talking about herself in the third person, in a high-pitched, lisping voice. I didnt want to play along, to pretend an empty chair contained a family member or to wallop a cushion with a baseball bat. I was too self-conscious, painfully alert to my own ridiculousness, and even though I found Annas antics mortifying I was aware she was inhabiting a kind of freedom to which I did not have access.

Whenever I could, Id suggest we ditch talking in favour of a massage. I didnt have to undress completely. Anna would don a stethoscope and lightly work at odd places on my body, not kneading but seeming instead to directly command muscles to unclench. Periodically shed lean over and listen, the bell of her stethoscope pressed against my stomach. More often than not, I experienced a sense of energy streaming through my body, moving through my abdomen and down my legs, where it tingled like jellyfish tentacles. It was a nice feeling, not sexual exactly, but as if an obstinate blockage had been dislodged. I never talked about it and she never asked, but it was part of why I kept coming back: to experience this newly lively, quivering body.

I was twenty-two when I began seeing Anna, and the body was at the centre of my interests. When bodies are discussed, especially in popular culture, it has often meant a very circumscribed set of themes, largely to do with what the body looks like or how to maintain it at a pinnacle of health. The body as a set of surfaces, of more or less pleasing aspect. The perfect, unattainable body, so smooth and gleaming it is practically alien. What to feed it, how to groom it, the multiple dismaying ways in which it might fail to fit in or measure up. But the element of the body that interested me was the experience of living inside it, inhabiting a vehicle that was so cataclysmically vulnerable, so unreliably subject to pleasure and pain, hatred and desire.

Id grown up in a gay family in the 1980s, under the malign rule of Section 28, a homophobic law that forbade schools from teaching the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship. To know that this was how the state regarded your own family was to receive a powerful education in how bodies are positioned in a hierarchy of value, their freedoms privileged or curtailed according to more or less inescapable attributes, from skin colour to sexuality. Each time I went to therapy I could feel the legacy of that period in my own body, as knots of shame and fear and rage that were difficult to express, let alone dissolve.

But if my childhood taught me about the body as an object whose freedom is limited by the world, it also gave me a sense of the body as a force for freedom in its own right. I went to my first Gay Pride at nine, and the feeling of all those marching bodies on Westminster Bridge lodged inside me too, a somatic sensation unlike anything Id previously experienced. It seemed obvious to me that bodies on the streets were how you changed the world. As a teenager terrified by the oncoming apocalypse of climate change, I started attending protests, becoming so immersed in the environmental direct action movement that I dropped out of university in favour of a treehouse in a Dorset woodland scheduled to be destroyed for a new road.

I loved living in the woods, but using my own body as a tool of resistance was gruelling as well as intoxicating. The laws kept changing. Policing had become more aggressive and several people I knew were facing long prison sentences for the new crime of aggravated trespass. Freedom came at a cost, and it seemed that the cost was bodily too, the loss of physical liberty an omnipresent threat. Like many activists, I burned out. In the summer of 1998, I sat down in a graveyard in Penzance and filled out an application for a degree in herbal medicine. By the time I started seeing Anna, I was in my second year of training.