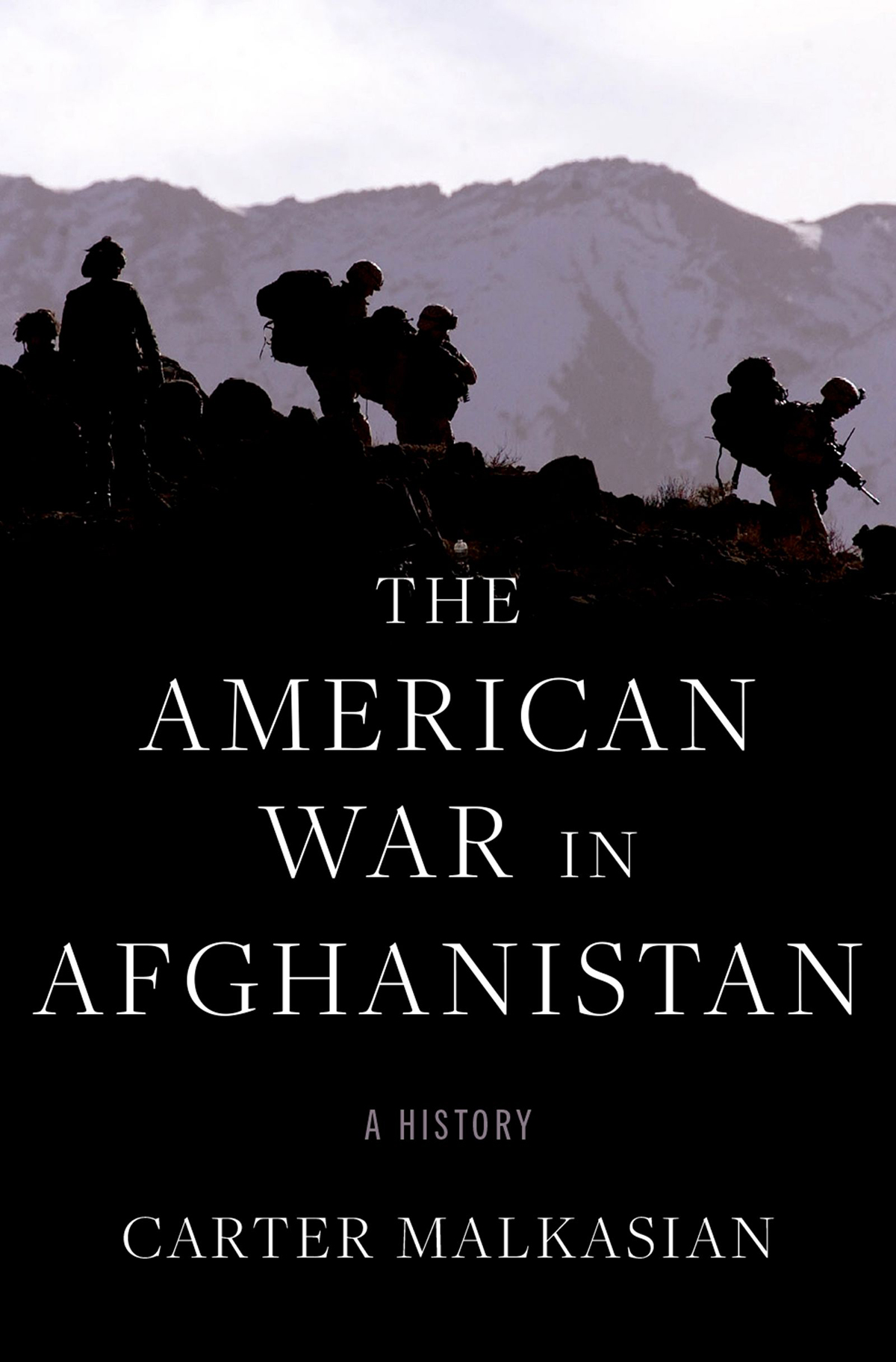

The American War in Afghanistan

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Malkasian, Carter, 1975 author.

Title: The American war in Afghanistan: A History / Carter Malkasian.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] |

Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020056939 (print) | LCCN 2020056940 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780197550779 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197550793 (epub) | ISBN 9780197550809

Subjects: LCSH: Afghan War, 2001United States. | Afghan War, 2001

Classification: LCC DS371.412 .M327 2021 (print) | LCC DS371.412 (ebook) |

DDC 958.104/7373dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056939

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056940

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197550779.001.0001

Table of Contents

The heart of Afghanistan was the countryside, the atraf. There in small villages of mud-walled homes, surrounded by fields of wheat, corn, or poppy, most Afghans lived. Bearded men with worn hands worked the fields. Barefoot boys and girls played on dirt paths. Women toiled unseen within the walls, bounded in shroud. Every village had a simple, single-room mosque where men gathered to pray. Other than cell phones, cars, and assault rifles, the 21st century was invisible.

From 2001 to 2021, Americans passed through the countryside and its villages. Patrolling in green or tan camouflage, loaded with body armor, a helmet, ammunition, and water, with an M-4 or M-16 assault rifle or maybe a belt-fed machine gun cradled in their arms, they wound their way through fields and around the villages. Sometimes they staked a post out of brown dirt-filled HESCO barriers and squatted for a year or two. Sometimes with glowing green night vision they burst in during the small hours on a raid, and then disappeared. And sometimes rifles hammered, explosions cracked, and a brother was carried away. Jang peh atraf kay die, say the Afghans. War is in the countryside.

On the outskirts of any village were mounds of gray rocks. They rested on a barren patch, or on high ground overlooking the fields, or shaded amid pine trees, or honored by a rickety wooden fence. A flaga strip of cloth tied to a long bamboo polewas planted in each. From afar, the whole plot was a fluttering multi-colored mass. It was the graveyard. For 40 years the graveyards grew. The tale of loss could be heard in Hamid Karzais deep flowing Pashto when he sat face to face with the Taliban in 2019:

You have all seen, since three, four, five, six years, nay longer, that upon our dear soil across Afghanistan... from Kunduz, to Khost, to Herat, to Badakhshan, to Faryab, to the environs of Kabul, that... two graves lie side by sidedwa kabira tsang peh tsang prot dee. On one is a black,

Americans and Afghans fought in Afghanistan, against each other and side by side, for more than 19 years. It was Americas longest war. Through 2021, it crossed four presidentsGeorge W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, Joseph Biden. Fifteen US generals commanded there. Hundreds of thousands of US troops and diplomats were deployed. Thousands were killed or wounded. For a time it was the good war. In the wake of the attacks of September 11, Americans thought intervention just. In its latter years the war ceased to be good. It became only long and futile.

I decided to write a book about the whole Afghan War in 2013 after reading William Dalrymples majestic Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, about Britains first catastrophic foray into Afghanistan. His storytelling, thick with Dari poems and Afghan viewpoints, captured my admiration. Though I knew I could never match his skill, I wanted to follow his example and write a full history of Americas war in Afghanistan. Such a history, that drew on wide-ranging sources, had yet to be written.

I had just become the political advisor to General Joseph Dunford, the commander of US and allied forces for all Afghanistan. I had already spent several months in Kunar province and nearly two years in Garmser, Helmand province, where I learned Pashto. I had written a book on the latter, War Comes to Garmser: Thirty Years of War on the Afghan Frontier. General Dunford asked me to talk to Afghan leaders and visit the various regions to understand the local situation. The new job would allow me to see much of Afghanistan and meet with Afghans from different backgrounds and allegiances. I had that job until the end of August 2014 when General Dunford returned to the United States. A book on the whole war seemed possible from this vista.

My problem was that the war did not end. In fact, I was actually witnessing the beginning of a whole new phase. After 2014, I remained with General Dunford as he became chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, senior officer for the entire US Armed Forces. Serving as his advisor, I saw the war from an even higher viewpoint. I continued to visit Afghanistan regularly. In 2018 and 2019, I found myself spending months helping General Scott Miller, commander of US forces, in Afghanistan, and participating in peace talks in Qatar with Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, US special envoy for peace talks with the Taliban. The war escalated and evolvedyet did not end. For years, I thought waiting for the end was going to turn out to be unrealistic. Then, on April 14, 2021, President Joseph Biden declared the final US military withdrawal would be completed by September 11 of that year. That denouement is still fresh, too close for reasonable perspective. But the events leading up to it can be understood and reflected upon. In that sense, the book ended up being a full history of Americas Afghan War from 2001 to 2021.

The Afghan War has a rich literature.. Steve Colls tome, Directorate S: The C.I.A. and Americas Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, is an authoritative text on what happened behind closed doors in the halls of power and is essential reading for the details of Pakistani policy and US peace efforts.

This book synthesizes earlier works into a single history while incorporating my own new research. The time in Kunar and Helmand and the 17 months with General Dunford and various visits since are sources of discussions, interviews, and firsthand observation of events. I have been to 15 provinces, with the most time spent in Helmand and Kunar, and Kandahar as a distant third. I have thoroughly reviewed Pashto written sources, including newspapers, books, and magazines. Friends have gone to Pakistan to bring me Taliban histories, documents, propaganda, and poems. I have mined key Pashto texts written by Taliban, hitherto unreferenced by Western scholars. These include the biography of Mullah Omar by his former spokesman, Abdul Hai Mutmain; the memoir of former Taliban foreign minister, Wakil Ahmed Mutawakil; and the history of the Taliban movement by Abdul Salam Zaeef, former ambassador to Pakistan and one of the most respected figures in Afghanistan. Additionally, I have conducted indirect surveys in which contacts interviewed dozens of Taliban fighters and commanders. And I have spoken directly to Taliban in Doha, in Kabul, and in the provinces.