1943

Days of Peril, Year of Victory

V ICTOR B ROOKS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2021 by Victor Brooks

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brooks, Victor, author.

Title: 1943 : days of peril, year of victory / Victor Brooks.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Lyons Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Military historian Victor Brooks argues that the year 1943 marked a significant shift in the World War II balance of power from the Axis to Allied forces Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020052621 (print) | LCCN 2020052622 (ebook) | ISBN 9781493045082 (cloth) | ISBN 9781493045099 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: World War, 1939-1945. | United StatesArmed ForcesHistoryWorld War, 1939-1945.

Classification: LCC D755.5 .B76 2021 (print) | LCC D755.5 (ebook) | DDC 940.54/1273dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052621

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052622

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

C ONTENTS

Guide

Correspondents related stories of hand-to-hand bayonet duels and extremely close quarters combat that taught them that jungle fighting differs radically from any other kind: one American soldier pitted against one enemy soldier. Americans must become independent, self sufficient fighters experienced with a rifle, grenade and bayonet, capable always of personally killing his enemy and saving himself.

As American casualties mounted, a single chaplain often rotated among Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish funeral services, while wary armed bodyguards eyed the treetops and bushes for potential enemy snip-ers. Sgt. Herman Bottcher, a German immigrant to the United States, led an assault force that finally opened a passable corridor between already captured Buna village and the still contested Buna Mission and was given a spot promotion to captain for his bravery. General Eichelberger, with MacArthurs win or die exhortation still ringing in his ears, was frequently photographed with a tommy gun, and as he stepped over a long line of enemy bodies was quoted as exclaiming, What! Another 100 Japs killed; isnt it beautiful!

Eichelbergers assault force for what would eventually become the Battle of Buna was the 32nd Infantry Division, composed primarily of National Guard enlistees from Wisconsin and Michigan and the 41st Division, another National Guard unit centered around personnel from Oregon and Washington. As the Americans and allied Australian units set off on their long march across the Kokoda Trail, MacArthur, never a person to miss an opportunity for a dramatic gesture, wished Eichelberger good luck and then insisted, Take Buna, Bob, or dont come back alive!

However, Douglas MacArthur also quickly appreciated the strategic value of a port town that could become a jumping-off point for a Japanese invasion of Australia, and reinforcements were funneled into the area at a rapid pace. These included the Australian 14th Infantry Brigade, the largely African-American 96th Engineer Battalion, an American antiaircraft battalion, and other assorted units that turned the sleepy town into a major military base that could most likely repulse the enemy assault forces.

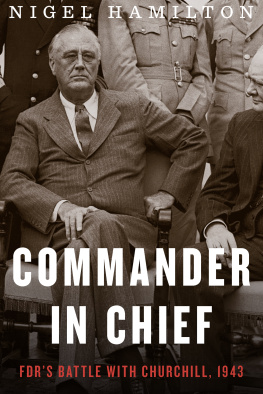

MacArthur, along with his wife and young son, underwent excruciating bouts of seasickness after boarding Lt. John Bulkeleys PT-41 in a meandering odyssey from Corregidor down to the Mindanao city of Cagayan, where the small party was expected to board B-17 bombers for the flight to Australia. Seasickness was quickly exchanged for airsickness on a fifteen-hundred-mile flight in the cramped bombers, never designed to carry passengers. When MacArthur reached Darwin on St. Patricks Day morning, the general received a new shock that the Army that he was told he would command in an early attempt to relieve Bataan simply did not exist and, in fact, a Japanese invasion of Australia was expected shortly. The general had commanded over seventy-five thousand men on Bataan. Now, with most of the Australian army fighting abroad, MacArthur discovered that the Allied garrison in Australia was closer to twenty-five thousand men. Despite the initial shock, the general held a press conference that proved to be a turning point, as he told the press, I have come to Australia to organize an offensive against Japan I came through, and I shall return. Bataan and then Corregidor would soon surrender, and the proud tradition of the Japanese honor code would become a mockery in the Bataan Death March and subsequent prison camp mistreatment of American prisoners that may very well have cost the life of every captured solder if their escaped commander did not return. For the next two and a half years, Douglas MacArthurs eyes were always on the emaciated American soldiers and the mistreated Filipino civilians who were unwilling protagonists in the Imperial fraud of Asia for Asians. However, the defeat in the jungle of Bataan could only be eventually redeemed by an initial American victory in the equally challenging jungles of New Guinea, and the first step on the trip back to Bataan began at a small village in another jungle.

CHAPTER 12 The Battle for Salerno

As nurses and doctors in open-air hospitals near the tip of Bataan heard the enemy guns get a bit closer with each food-scarce day, Franklin Roosevelt and Gen. George Marshall realized that while there was no way that the garrison could be relieved with much of the Pacific Fleet sitting on the bottom of Pearl Harbor, there was little sense in providing the enemy with the propaganda coup of capturing the most senior American commander in the Pacific Theater. While MacArthur insisted that he would not be taken alive, rumors that the enemy might exhibit the captured general in a cage throughout the Empire helped to expedite the presidential order that the American commander was expected to leave the Philippines and transfer his headquarters to theoretically organize a rapid return to the Philippines with substantial reinforcements.

As the competing battle plans for the Axis defense of the Italian mainland were debated in the dusk to dawn Fhrer Meetings, punctuated by Hitlers seemingly endless supply of reminiscences about his activities in World War I, a reality check came storming from the east. Hitler and his closest advisors had concocted a daring counteroffensive against an increasingly powerful Red Army. Operation Citadel was planned as an attack on a huge Soviet assault force in the vicinity of Kursk, with more than a sprinkling of unwarranted optimism that a major victory on those plains would at least temporarily force the Russians to regroup in a time-demanding process that would allow a concentration of German forces that might achieve enough Axis victories to entice some portion of the Allied high command to propose a compromise settlement.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.