Copyright

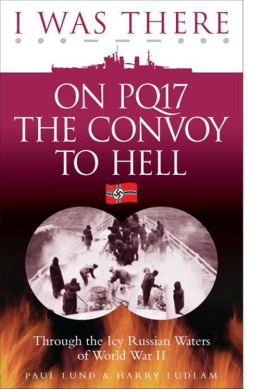

First published in Great Britain in 1978 by W. Foulsham & Co. Ltd

Copyright 1978 Paul Lund and Harry Ludlam

The moral right of the authors has been asserted

All rights reserved

Epub ISBN 9780572041045

Kindle ISBN 9780572041038

The Copyright Act prohibits (subject to certain very limited exceptions) the making of copies of any copyright work or of a substantial part of such a work, including the making of copies by photocopying or similar process. Written permission to make a copy or copies must therefore normally be obtained from the publisher in advance. It is advisable also to consult the publisher if in any doubt as to the legality of any copyright which is to be undertaken.

W. Foulsham & Co. Ltd

Capital Point, 33 Bath Road

Slough, Berkshire

SL1 3UF, England

www.foulsham.com

Table of Contents

Introduction

'Harry Tate's Navy'

The Royal Naval Patrol Service was a very special service indeed. It was, in fact, a navy within the Royal Navy, down to the unique distinction of having its own exclusive silver badge, worn by seagoing officers and ratings. Its unlikely headquarters was a municipal pleasure gardens by the sea at Lowestoft with the odd name of Sparrow's Nest. Its fighting fleet consisted of hundreds of coal-burning trawlers, drifters and whalers brought in from the fishing grounds and dressed for war with ancient guns, most of which had been used to fight World War I and some the war before that.

Fish holds became messdecks, and trawls were swapped for mine-sweeping gear; asdic sounding equipment was fitted for antisubmarine patrol. Then off went the fishermen to the bitter waters of the Northern Patrol, to the Channel and 'E-boat Alley', to the Atlantic and Arctic convoys, to the U-boat ridden U.S. east coast, Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East.

Vessels, many of them as old or older than their outdated guns, made astonishing journeys of thousands of miles, fighting in strange waters and braving heavy odds. Other Patrol Service men helped to crew the small nucleus of Admiralty-built trawlers which existed at the beginning of the war, and others as they left the shipyards, besides a variety of requisitioned craft including armed yachts, boarding vessels, and paddle-steamers converted for minesweeping.

To start with, the ships of the Patrol Service were manned almost exclusively by skippers, mates and men of the Royal Naval Reserve, except for communications ratings, who came from a white-collar world. The crews were fishermen, tugmen and lightermen, and their officers were skippers from the fishing fleets, with a leavening of senior ranks from the Royal Navy and rnr to ensure that a modicum of naval discipline was observed.

But as the war dragged on, the huge expansion in Patrol Service shipping had to be matched in its crews, and so there poured into Sparrow's Nest an ever-increasing flood of ordinary civilians from all walks of life, many of whom had not been to sea even on a seaside pier. As they went off to join their ships, their ignorance of nautical matters was a source of wonder to the fishermen, who also found it hard to understand what these men were doing in their navy, while the outlook, customs and language of the seamen produced no less wonder among the white-collar brigade. Yet somehow, with tolerance and good humour on both sides, the mixing process worked.

However, in spite of all the efforts of the naval men in charge and the great influx of newcomers, including rnvr officers, the casual, haphazard atmosphere of the fishermen's navy persisted, as did its fiercely stubborn independence, if not downright cussed-ness. The fleet of rust-stained, weather-beaten fishing craft 'minor war vessels', in the official language of the Admiralty earned the nickname of 'Harry Tate's Navy', after the famous comedian of the 1920s and 30s who was eternally confounded by modern gadgets and contraptions, the embodiment of the ordinary man struggling with irritations he could not control.

So the 'sparrows in the Nest', as Lord Haw-Haw called them, went forth from the efficient madhouse of their central depot to fight the war in many parts of the world, facing enemy planes and warships, U-boats, E-boats, mines and terrible weathers with a courage, skill, endurance and determination which won the admiration of their comrades in the big ships.

Grim statistics tell the measure of the contribution by the Patrol Service in World War II, for at the final count it had lost more vessels than any other branch of the Royal Navy.

Starting with 6,000 men and 600 vessels, 'Harry Tate's Navy' grew to 66,000 men and 6,000 vessels of all descriptions. One very green Ordinary Seaman who joined it was a bank clerk named Paul Lund, and it is from his experiences, together with those of more than a hundred officers and men who generously contributed their diaries, letters, papers and fresh personal testimony, that this book has been written.

It hopes to tell for the first time the eventful story of His Majesty's other navy, just how it was.

The Death of 'Cocker'

Anything less like a British warship it would have been hard to imagine. She lay in Tobruk harbour, H.M.S. Cocker, an unlikely ship in unnatural waters, far, far from home.

Even her saucy name was unreal. She had been launched in the 1930s, all 300 tons of her, as the more prosaic Kos 19; for she was a sturdy Antarctic whaler, and had served her peacetime masters well in the most relentless of oceans, doing one of the toughest and bloodiest of jobs, that of killing whales. Now here she was, on a June day in 1942, lolling in warm waters, renamed and fitted out with guns, asdic and depth-charges, all the paraphernalia of war.

Requisitioned only the year before, Cocker, like others of her kin had been brought up from the bottom of the world for service in the Mediterranean as an anti-submarine vessel; but call her what you will, try to hide her under Admiralty grey paint, dress her crew in the rig of the day, still at sea doing a punishing fourteen knots, with her midship deck awash, she was an ugly duckling.

In her brief year of war so far she had been a maid of all work, escorting, towing, 'arse-end Charlieing', and had earned several commendations escorting supply ships along the North African coast on the Tobruk run.

On this day, as on many previous occasions, Cocker slipped out of Tobruk harbour just before dusk to carry out the necessary asdic sweep of the harbour approaches prior to the arrival of her charge, a single-funnelled freighter. Once the freighter appeared, Cocker and her infinitely more imposing companion ship, the naval corvette H.M.S. Gloxinia nearly three times her size would take up escort stations, and as fast as Cocker's tired reciprocating engines would allow, they would steam down to Alexandria and the 'big eats' at the Fleet Club which all the naval crews dreamed about.

On this night, however, there were snags. The wayward freighter did not appear at the appointed time, so Cocker swept and re-swept, probing with her asdic for any sign of the underwater enemy, whose habit it was to sit quietly outside harbours for just such situations as this. Her crew, still at 'leaving harbour stations', began to get irritable when the skipper showed no sign of setting the watch, which would have allowed most of the men to have gone below.

By now it was quite dark, and tiring of the constant pressure, with the added danger of crossing courses with her sister escort in the blackness, Cocker hove-to and carried out a 360 deg. sweep. The air was like velvet, the ship blacked out, yet all men were aware of the intense urgency. Didn't the crazy, laggardly merchantman realize that by dawn they ought to be well beyond the German dive-bomber range? Apparently not, so they cursed her, the slab-sided bastard, for the longer they waited for her to appear, the more certain they were to have Stukas with their breakfast.