Contents

Guide

Page List

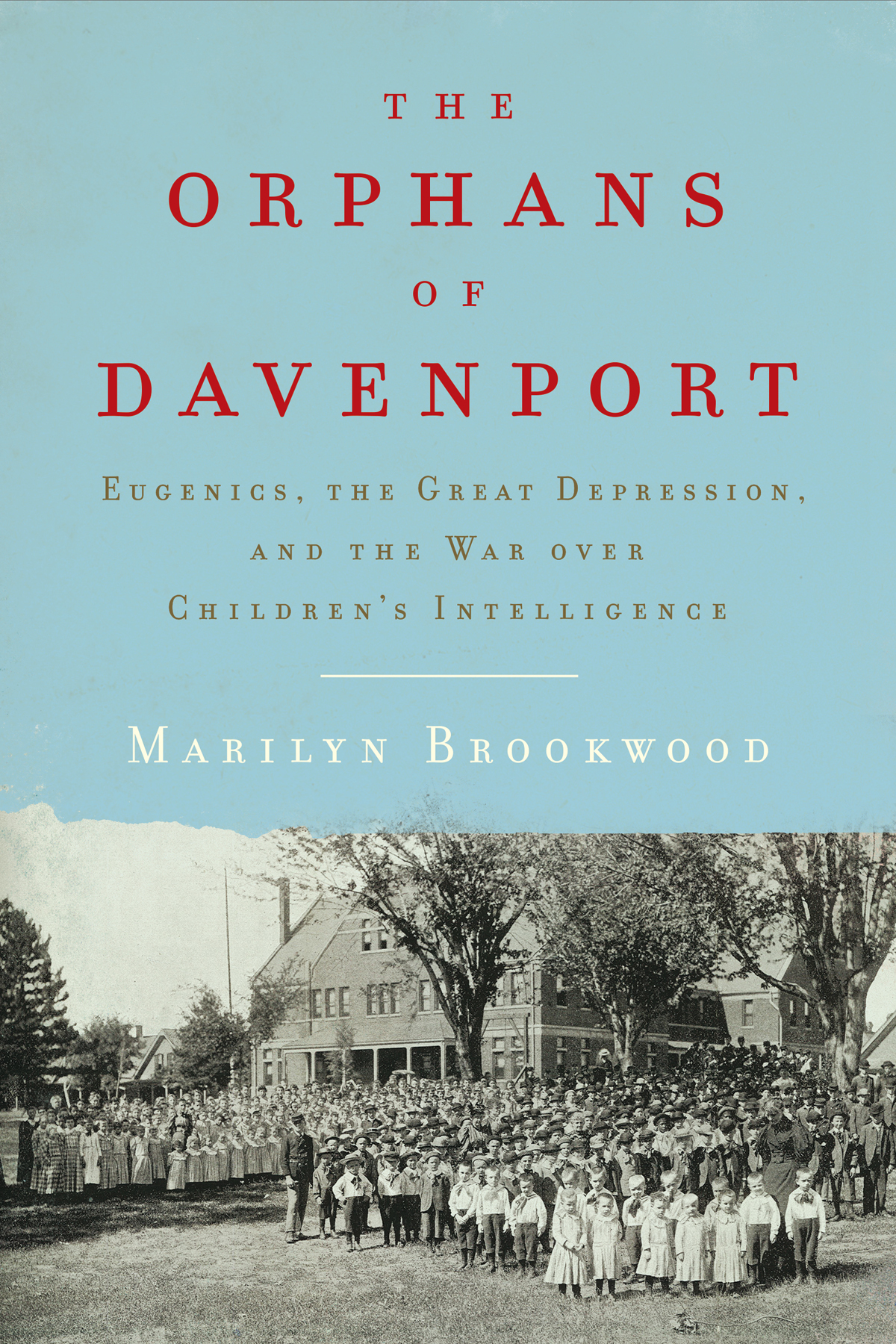

THE ORPHANS

OF DAVENPORT

Eugenics,

the Great Depression,

and the

War over Childrens Intelligence

MARILYN BROOKWOOD

The Orphans of Davenport is dedicated to the women with intellectual challenges living at the Woodward State Hospital for Epileptics and Home for the Feebleminded and the Glenwood Institution for Feebleminded Children, who without thought for themselves gave caring attention to Davenports orphans and radically changed the lives of so many, even today.

CONTENTS

A mericas eugenics era began at the start of the twentieth century and persisted into the early 1940s. During that period, intelligence tests were used to assess schoolchildren, as well as children and adults committed to institutions, immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, patients confined in mental hospitals, prisoners, those considered to be intellectually challenged, and army recruits. Intelligence test results, known as IQ scores, were reported on a scale in which the average range was between 90 and 109. A score from 110 to 119 was labeled superior, from 120 to 139, very superior, and a score of 140 and above was considered in the genius range. At the lower gradient, scores from 80 to 89 indicated low average or dull intelligence, and scores from 70 to 79 indicated borderline ability. But the IQ designations expressed something more particular for those in the lower IQ ranges when they slid from neutral descriptions to labels that stigmatized persons with those test scores. Those who scored from 50 to 69 were called morons, from 20 to 49, imbeciles, and those with scores below 20 were known as idiots. The umbrella term, feebleminded, identified those with scores of 70 or lower. From highest to lowest, the terminology was standard in medicine, psychology, education, and the law. These identifiers only began to be erased from professional usage in the 1960s, although by then they had entered the vernacular as repugnant slang. They are used in The Orphans of Davenport as they were used during the time the events in the narrative occurred.

THE ORPHANS OF DAVENPORT

T he young woman who presented herself for indigent maternity care at Iowa Citys University Hospital on May 7, 1934, appeared confused and gave the nurses two first names and four last names; because she would not or could not say which were really hers, hospital officials chose for her, and in Iowas public records she is Viola Hoffman. Hoffmans test result of 66 indicated that her IQ was well below the average range of 90109, and her diagnosis, moronism, became part of her official state of Iowa file. During this period, the terms moron, imbecile, and idiot were official identifiers for persons whose IQ test scores numerically fit categories of low intelligence.

Intelligence tests were first published in America between 1910 and 1916 and soon became tools in a mainstream public policy crusade called eugenics. Eugenicists believed that all human traits were biologically determined and inherited and that problematic traits, such as alcoholism, criminality, a tendency toward poverty, epilepsy, insanity, and promiscuity, among others, resulted from a persons low intelligence. Those who exhibited such traits could be institutionalized and sterilized, decisions often supported by IQ test score evidence. Designed to rid communities of the unfit, state governments and the educated class believed that the policies promoted a modern idealthe creation of a society of the ableto be achieved by improving the racial stock. A pioneer in the testing field, Lewis Terman, of Stanford University, called IQ tests a beacon of light for the eugenics movement. In addition, eugenicists promoted selective breeding, which encouraged the socially stable and well educated to have larger families.

In the service of eugenic goals, medical doctors diagnosed those who might have problematic conditions such as epilepsy or alcoholism, and court officials had responsibility for diagnoses of criminality and sexual perversions, including prostitution. Claiming that IQ tests were scientific, mental test psychologists became Americas acknowledged experts in the evaluation of the intelligence of persons accused of crimes, recruits in the United States Army, those confined to institutions, and hospital patients like Hoffman.

By the end of the 1920s, nearly all states had passed laws permitting the involuntary sterilization of those with low intelligence, most of them poor, most of them women. For some, sterilization may have been a choice freely made, but for othersparticularly women of low social statusthe power distance between those designated for the procedure and medical or court officials made refusal difficult.

Before her babys birth, doctors informed Hoffman that her delivery would be by cesarean section. Although the reasons for this are not included in her case history, when she learned of that decision she asked to be sterilized. Because she was now considered feebleminded, a state guardian was appointed to sign her sterilization consent. (Iowa was one of the few states that required consent.) It is impossible to know whether sterilization was coercively suggested to Hoffman or whether she directly requested it. Either way, for her doctor it would have been a routine procedure. From the perspective of most ordinary people, human ability and success were determined by genetics and not environment and accounted for the superiority of middle-class and upper-class whites. Therefore, Hoffmans sterilization would have been viewed as beneficial to society and to Hoffman herself: it would free her from the burden of raising a child whose dysgenic traits and unfortunate heredity would lead to a hopeless life. Better to prune the withering branch of the genetic tree.

In July, after Hoffman delivered a normal baby boy, whom she named Wendell, her mental status deteriorated further. Although she took care of her newborn son, she was unaware that she was his mother. Her hallucinations increased and she stopped keeping herself clean. Six weeks later doctors diagnosed her as insane and committed her to Clarinda, an Iowa state hospital for the mentally ill. Not considered by authorities who evaluated her were the traumatic events that occurred during her pregnancy when her husbandwho had already been married three timesdivorced and abandoned her. Hoffmans appearance of mental illness may have been related to antepartum depression, that is, depression that occurs during pregnancy. Along with postpartum depression, both conditions are recognized today as treatable with psychotherapeutic and medical interventions.

With his mother institutionalized, Wendell spent his first year in a Des Moines juvenile center. In the summer of 1935, when her son was 1 year old, Iowa declared Viola Hoffman cured of mental illness and released her to the care of a sister in Chicago. The state would have permitted Hoffman to resume custody of her son, but instead she chose to relinquish her parental rights. During the Great Depression, a divorced mother with a history of mental illness would have faced nearly insurmountable economic and social barriers to finding work and successfully caring for herself and a young child. Officials therefore transferred Wendell, now a ward of the state, 170 miles east, to the nursery at the Davenport Home, Iowas principal state-run orphanage.