Contents

For Penny, who makes it all possible

Tonight the sun goes down on more suffering than ever before in the world.

Winston Churchill, 6 February 1945

We were living an existence in which peoples lives had absolutely no value. All that seemed important was to stay alive oneself.

Lieutenant Gennady Ivanov, Red Army

INTRODUCTION

A dictionary defines Armageddon: The site of the decisive battle on the Day of Judgement; hence, a final contest on a grand scale. The last campaigns of the Second World War in Europe locked in bloody embrace more than a hundred million people within and without the frontiers of Hitlers Greater Reich. Their outcome drastically influenced the lives of many more. The Second World War was the most disastrous human experience in history. Its closing months provided an appropriately terrible climax.

Armageddon has its origins in my earlier book Overlord, which described the 1944 D-Day invasion of Europe and the campaign in Normandy. The narrative ended with the American and British breakthrough in August, followed by a triumphant dash across France. Many Allied soldiers believed that the collapse of Hitlers empire must swiftly follow. I concluded Overlord:

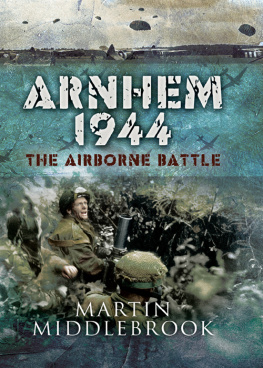

The battles in Holland and along the German border so often seem to belong to a different age from those of Normandy that it is startling to reflect that Arnhem was fought less than a month after Falaise; that within weeks of suffering one of the greatest catastrophes of modern history, the Germans found the strength... to prolong the war until May 1945. If this phenomenon reveals the same staggering qualities in Hitlers armies which had caused the Allies such grief in Normandy, it is also another story.

The early part of this book is that story. The starting point was a desire to satisfy my own curiosity about why the German war did not end in 1944, given the Allies overwhelming superiority. It is often asserted that in the west they had to overcome a succession of great rivers and difficult natural features to break into Hitlers heartland. Yet the Germans 1940 blitzkrieg easily surmounted such obstacles. In 194445, the Allies were masters of armoured and air forces greater than the Nazis ever possessed.

Most works on the last months of the war address either the Eastern or Western Fronts. This one aspires to view the story as a whole. The Soviets were separated from the Anglo-Americans not only by Hitlers armies, but by a political, military and moral abyss. I have attempted to explore each side of this, to set in context the battles of Patton and Zhukov, Montgomery and Rokossovsky. I have, however, omitted the Italian campaign. It exercised a significant indirect influence upon the struggle for Germany, absorbing a tenth of the Wehrmachts strength in 194445, but its inclusion would have overwhelmed my narrative. Beyond archival research, I have met some 170 contemporary witnesses in Russia, Germany, Britain, the United States and Holland. This is the last decade in which it will be possible usefully to conduct such interviews. Many people recall their experiences vividly, but they are growing very old. Those fresh, fit, vital, often brave and handsome young men, whose deeds decided the fate of Europe sixty years ago, are today stooped and frail, the destiny of us all.

It was helpful to me that a generation ago, when researching earlier books, I met American and British generals and airmen who held senior posts such as Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Generals Pete Quesada, James Gavin, J. Lawton Collins, and Pip Roberts. Todays surviving military witnesses rarely held ranks beyond that of major. For the perspective of senior officers, in this book I have drawn extensively upon unpublished manuscripts and oral-history interviews, of which rich collections exist in the United States, Britain and Germany. All historians are grateful for the recent flood of privately published veterans memoirs. Because this book portrays a human tragedy, rather than a mere battlefield saga, I have also interviewed Russian and German women. Their wartime experiences deserve more attention than they have so far received, other than as victims of rape.

In Overlord, I argued that Hitlers army was the outstanding fighting force of the Second World War. There has since been a revisionist movement against such a view. Several writers, notably in the United States, have written books arguing that authors such as myself overrate the German performance. Some of the revisionists cannot be acquitted of nationalistic exuberance. An American military historian of my acquaintance observed justly, and without envy, that a best-selling colleague had taken to raising monuments rather than writing history, by producing a series of volumes which pay homage to the American fighting man.

A U.S. veteran of the north-west Europe campaign praises the works of Stephen Ambrose, saying: They make me and my kind feel really good about ourselves. There is absolutely nothing wrong with the creation of romantic records of military experience, which bring a glow to the hearts of many readers, as long as their limitations as history are understood. This book, too, tries to bring alive the experience of those who fought. Its chief purpose, however, is objective analysis. The defence of Germany against overwhelming odds reflected far more remarkable military skills than those displayed by the attackers, especially when all German operations had to be conducted under the dead hand of Hitler. Since I wrote Overlord, however, my own thinking has changednot about the battlefield performance of the combatants, but about its significance. Moral and social issues are at stake, more important than any narrow military judgement.

A cultural collision took place in Germany in 1945, between societies whose experience of the Second World War was light years apart. What the Soviet and German peoples did, as well as what was done to them, bore scant resemblance to the war the American and British knew. There was a chasm between the world of the Western allies, populated by men still striving to act temperately, and the Eastern universe in which, on both sides, elemental passions dominated. Although some individuals in Eisenhowers armies suffered severely, the experience of most falls within a recognizable compass of what happens to people in wars. The battle of Arnhem, for instance, is perceived as an epic. Yet the entire combat experience of many British participants was compressed into a few days. Barely three thousand men died on the Allied side. Among British veterans of north-west Europe, Captain Lord Carrington remembers with considerable affection his service with the Grenadier Guards tank regiment: Wed been together a long time. It may sound an odd thing to say, but it was a very happy period. We were young and adventurous. We were winning. One had all ones friends with one. We were a happy family. I do not extrapolate from this that British or American soldiers enjoyed themselves. Few sane people like war. But many found 194445 not unbearable, if they were fortunate enough to escape mutilation or death. Hardly any Americans felt the hatred for the Germans which Pearl Harbor, together with the Japanese cultural ethic expressed in the Bataan Death March, engendered towards the soldiers of Nippon.

It is a sombre experience, by contrast, to interview Russian and German veterans. They endured horrors of a different order of magnitude. It was not uncommon for them to serve with a fighting formation for years on end, wounds prompting the only interruptions. The lives of Stalins subjects embraced unspeakable miseries, even before the Nazis entered the story. I have met many people whose families perished in the famines and purges of the pre-1941 era. One man described to me how his parents, illiterate peasants, were anonymously denounced by neighbours as counter-revolutionaries, and shot in 1938 at a prison outside Leningradthe modern St. Petersburg. A woman listening to our conversation interjected: My parents were shot at that prison too! She employed the commonplace tones one might use in New York or London on discovering that an acquaintance had attended the same school.

Next page