John Nichol and Tony Renell

ARNHEM

The Battle for Survival

This book is dedicated to all those Arnhem veterans, military and civilian, who fought with such incredible courage and selfless dedication. Their fortitude in the face of overwhelming odds is an inspiration to us all.

I will not say that Arnhem was a defeat. Such men as they can never be defeated. They fought till they had nothing left to fight with and then fought on.

Dick Ennis, glider pilot

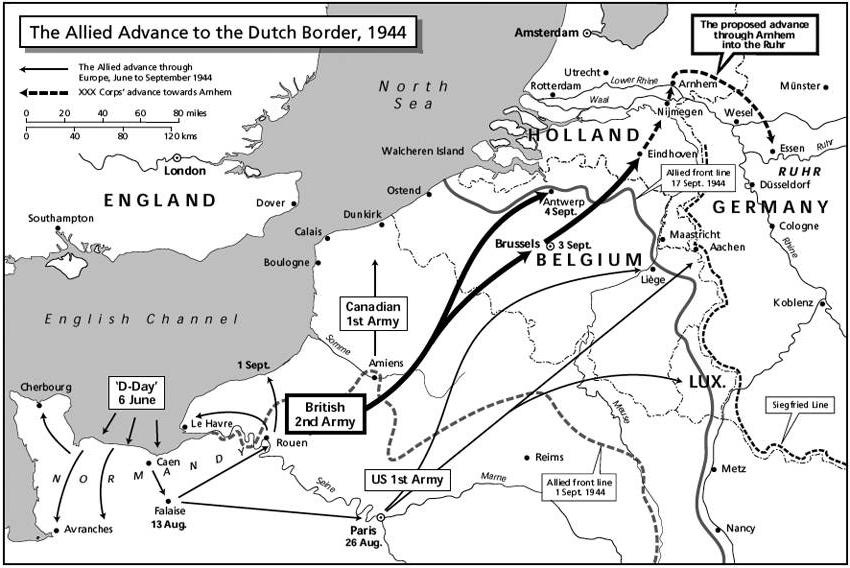

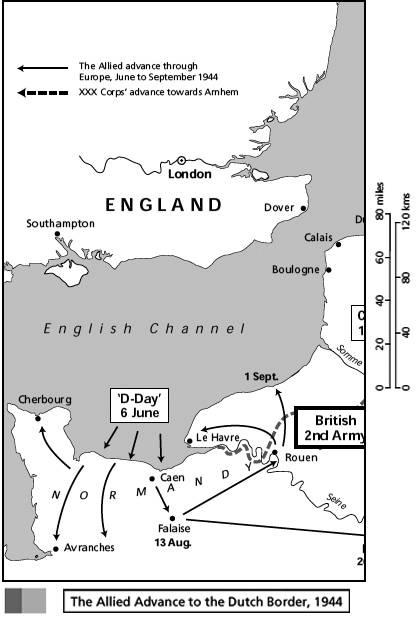

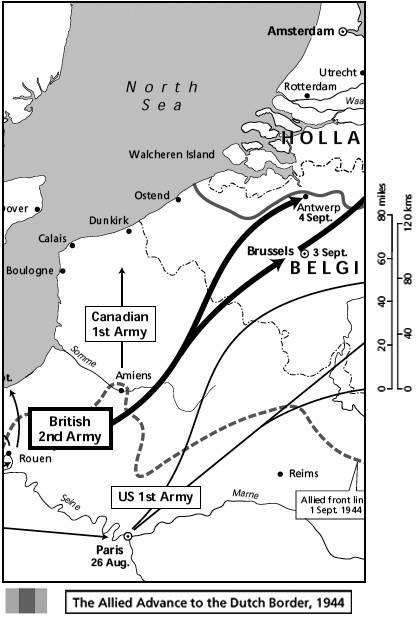

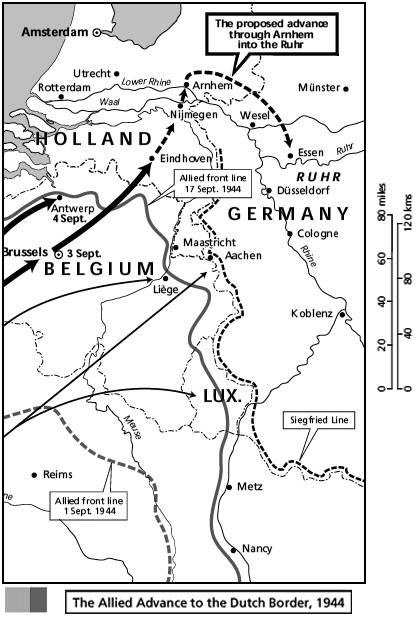

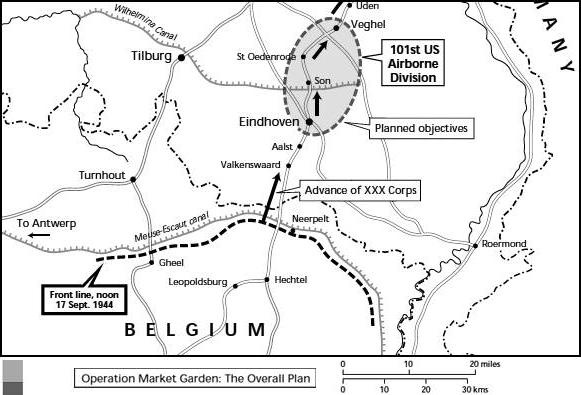

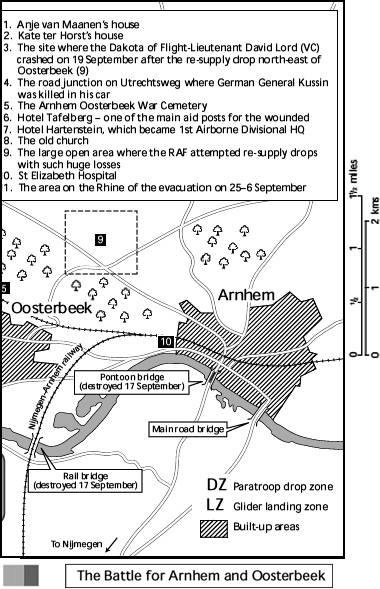

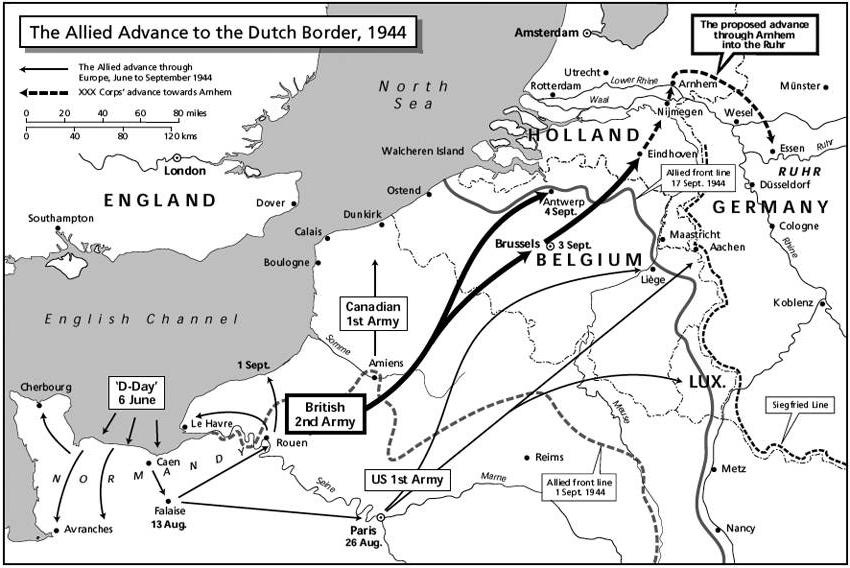

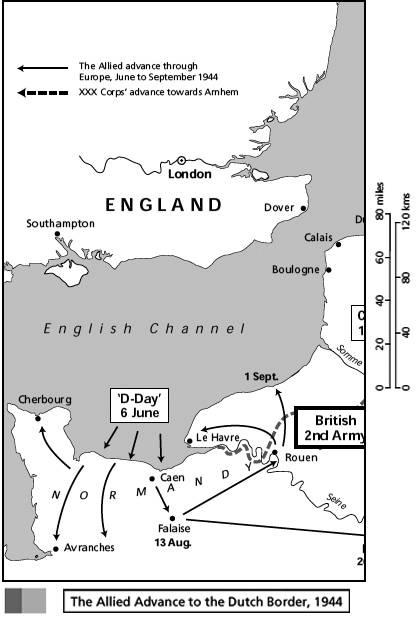

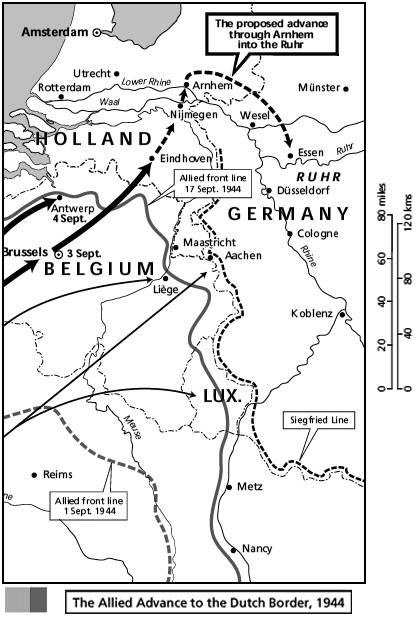

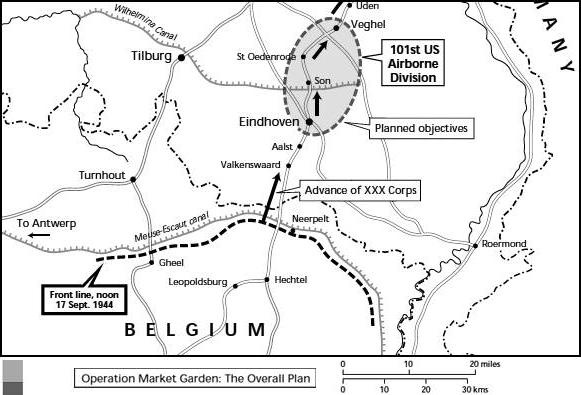

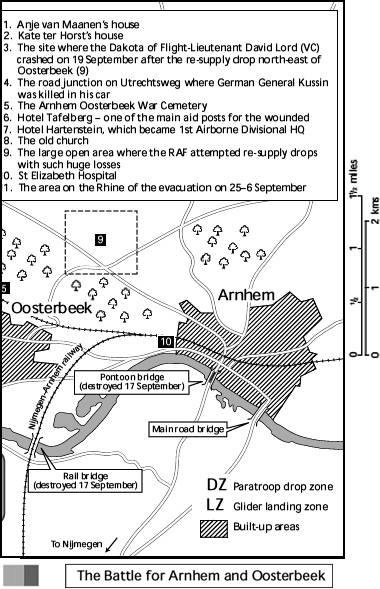

MAP 1

The Allied Advance to the Dutch Border, 1944

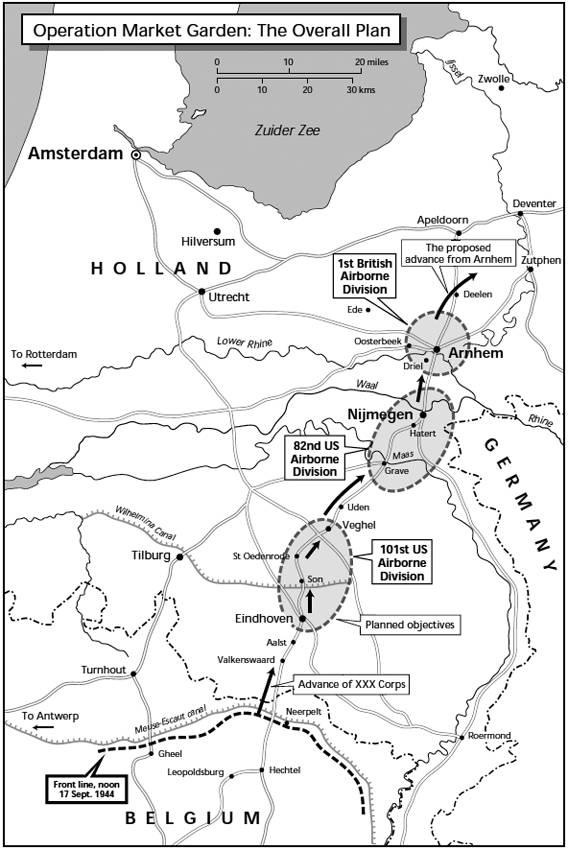

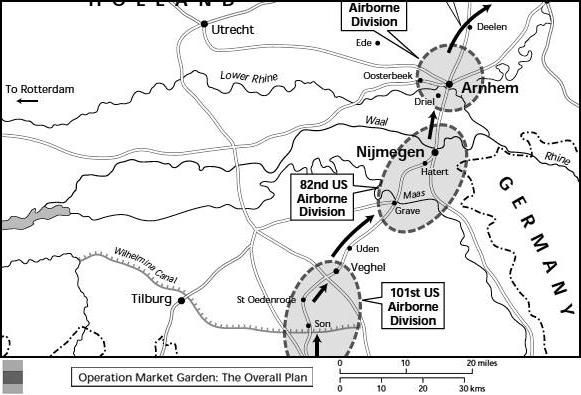

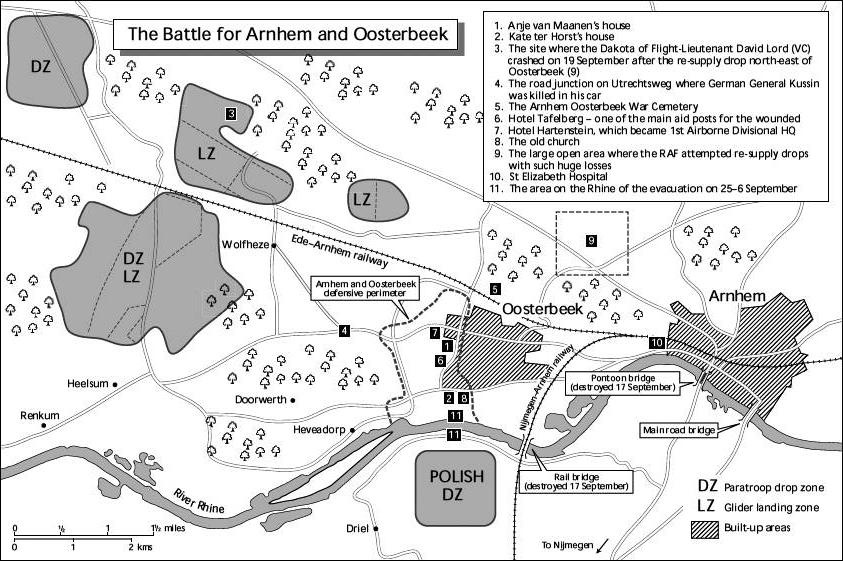

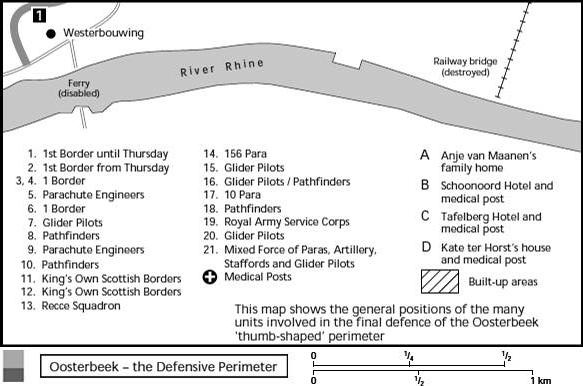

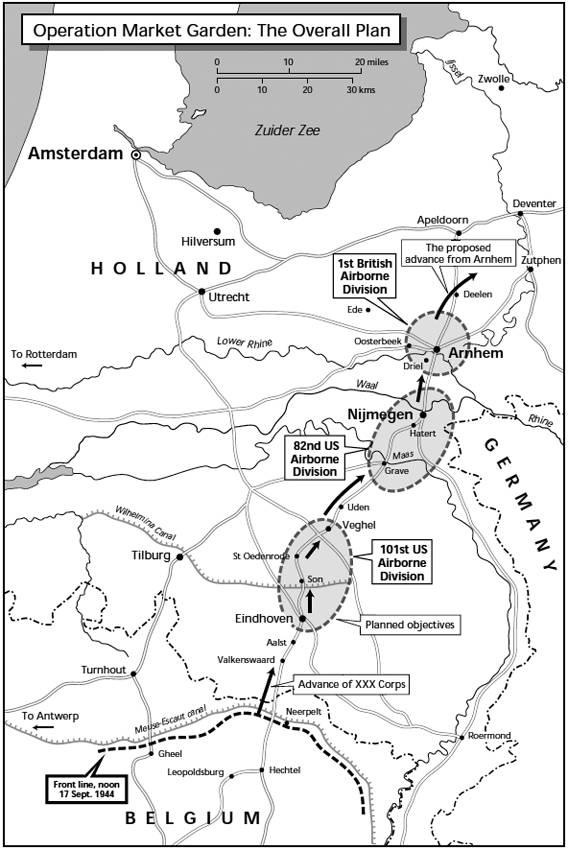

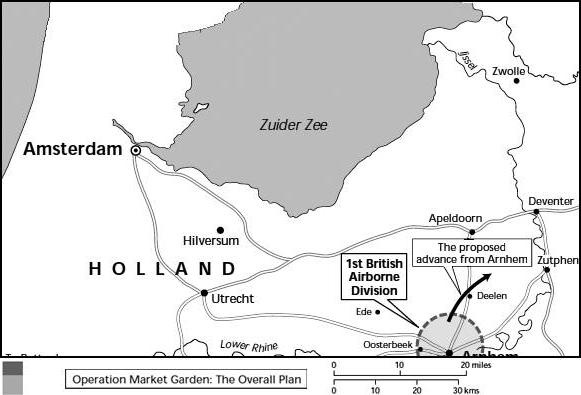

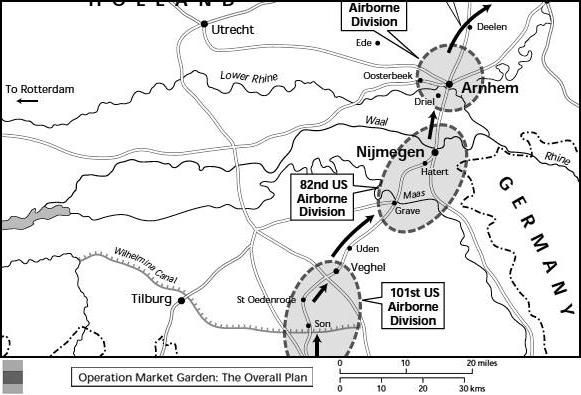

MAP 2

Operation Market Garden: The Overall Plan

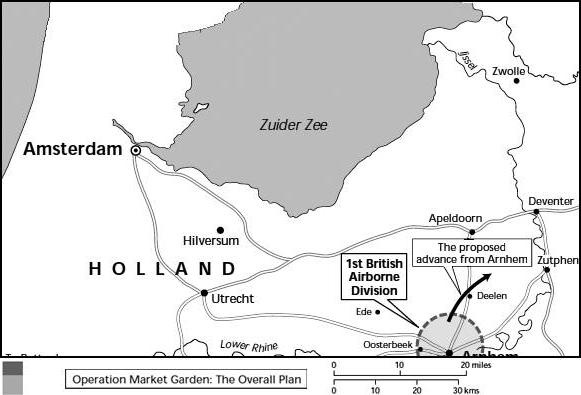

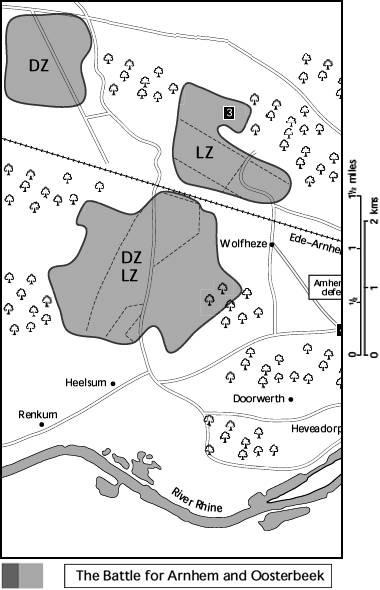

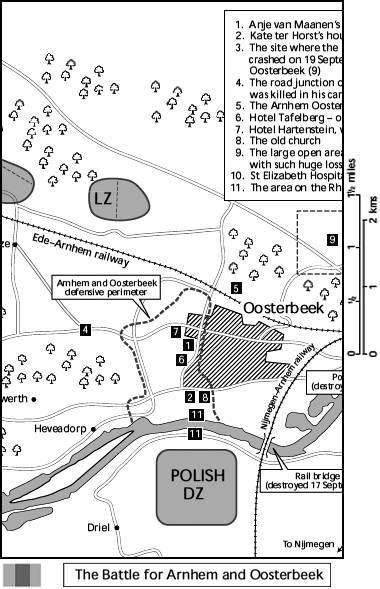

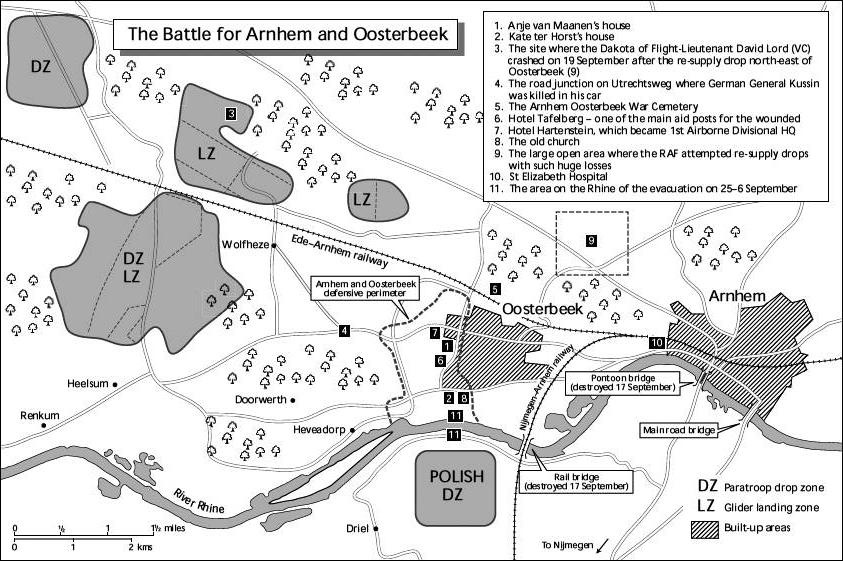

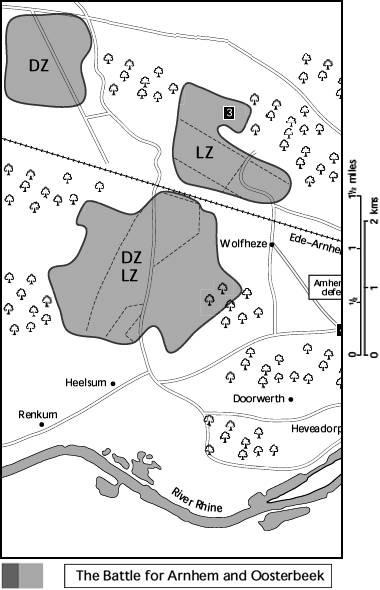

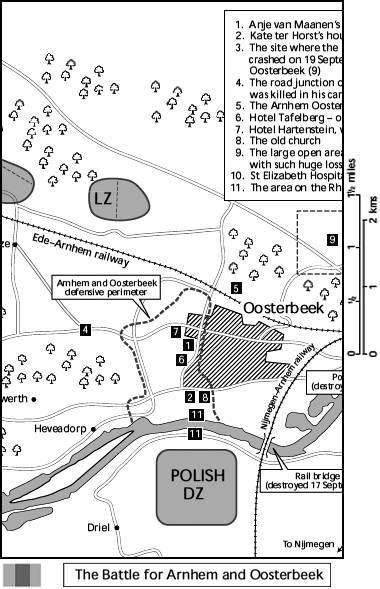

MAP 3

The Battle for Arnhem and Oosterbeek

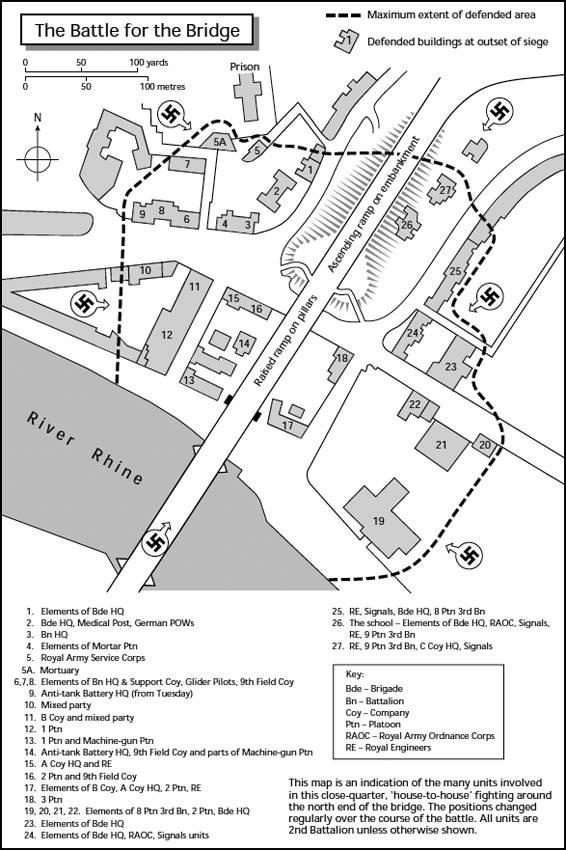

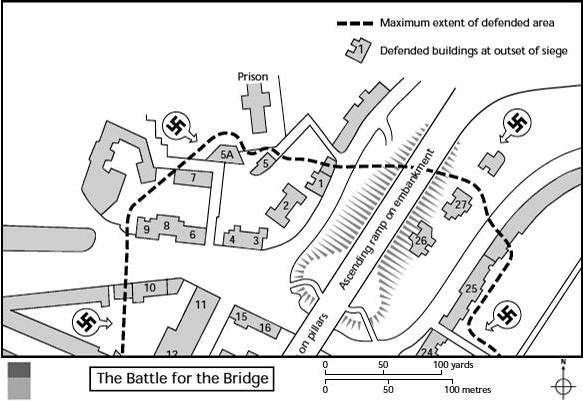

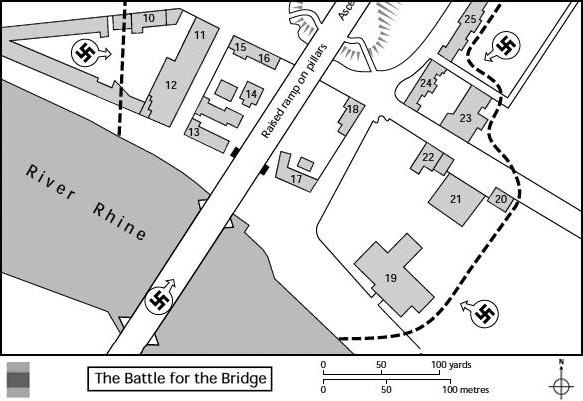

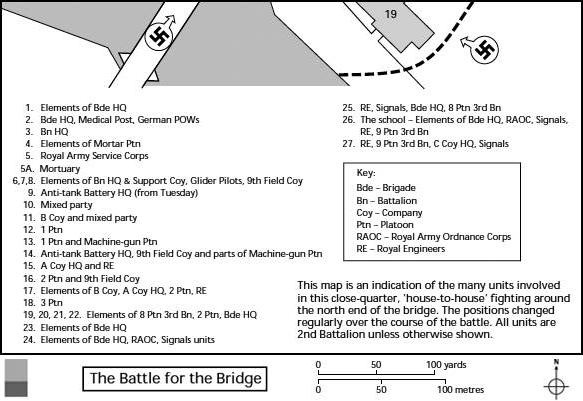

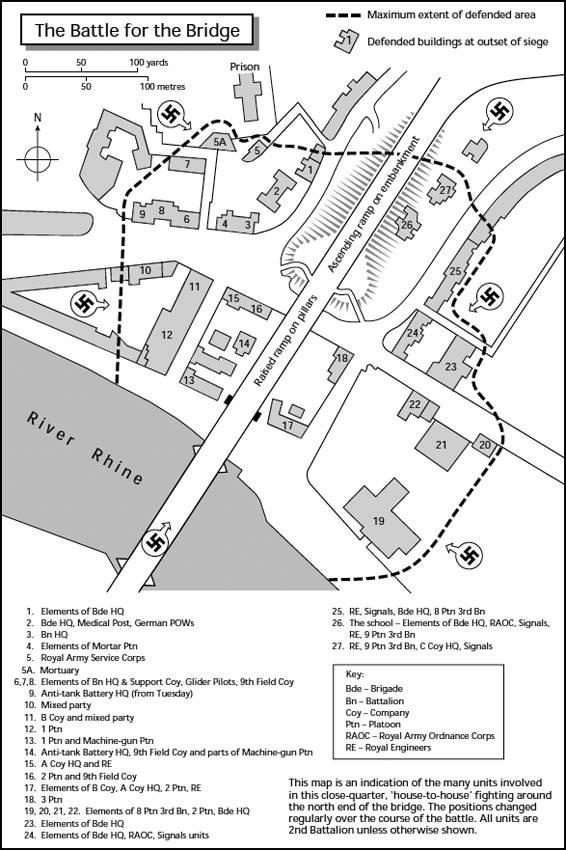

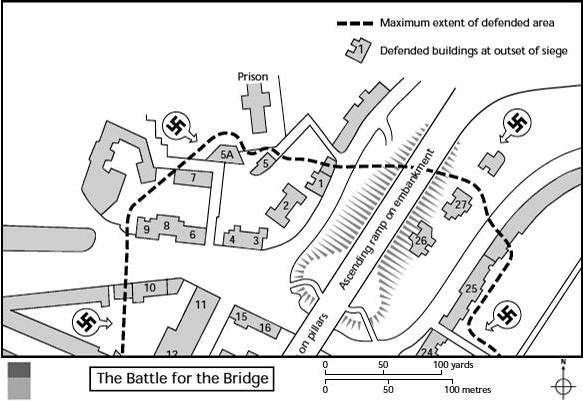

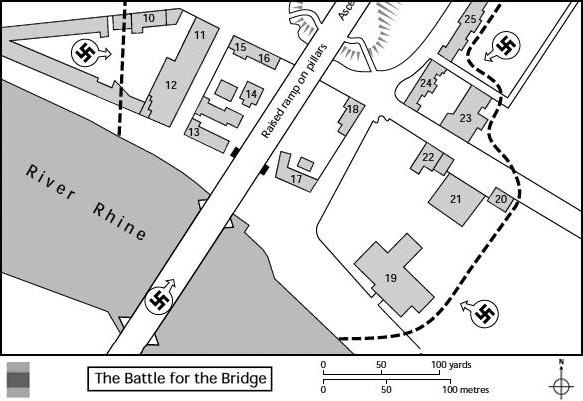

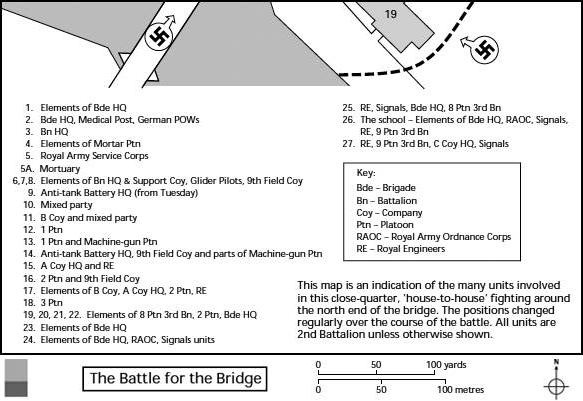

MAP 4

The Battle for the Bridge

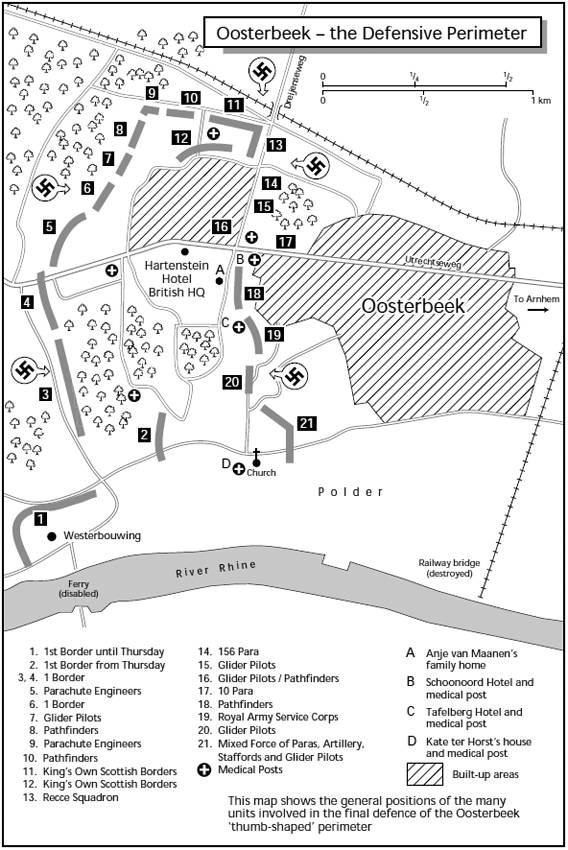

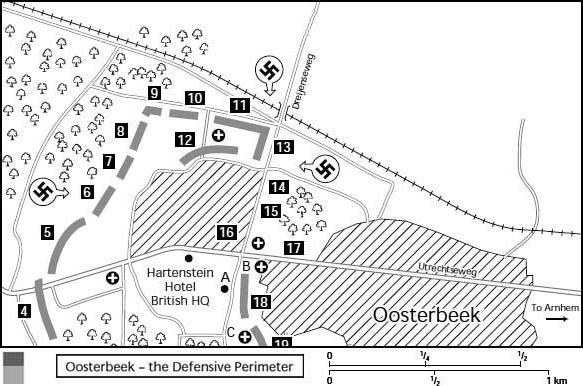

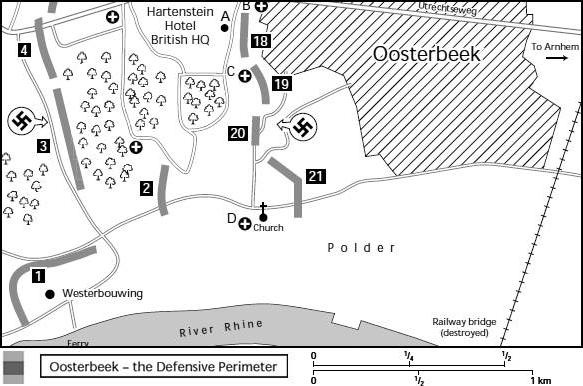

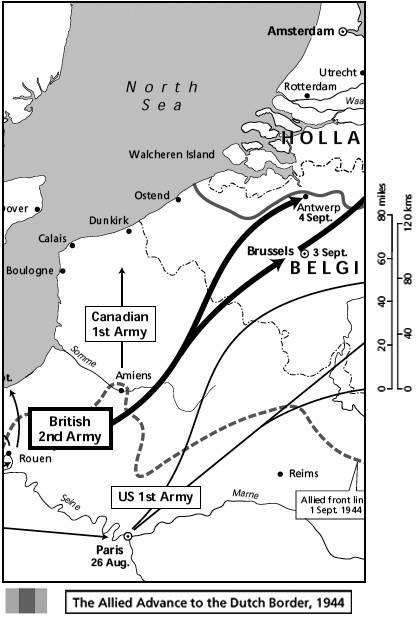

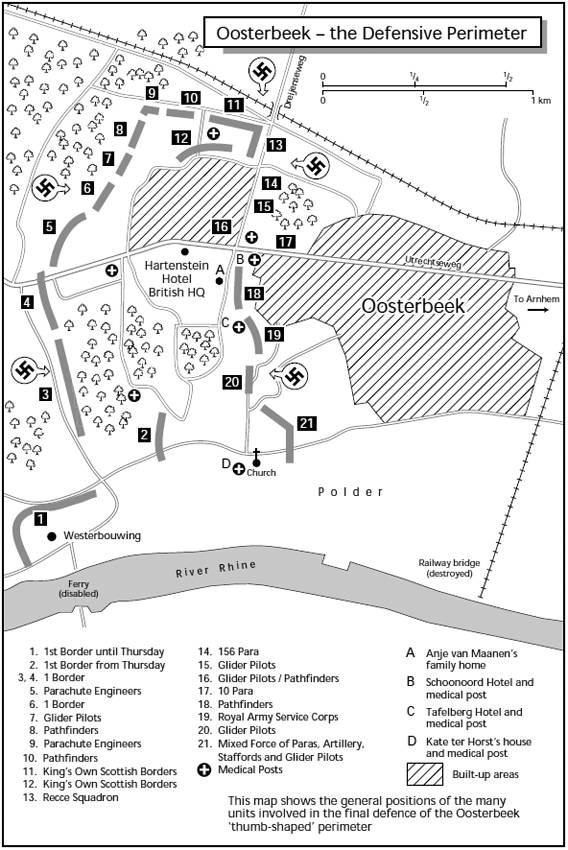

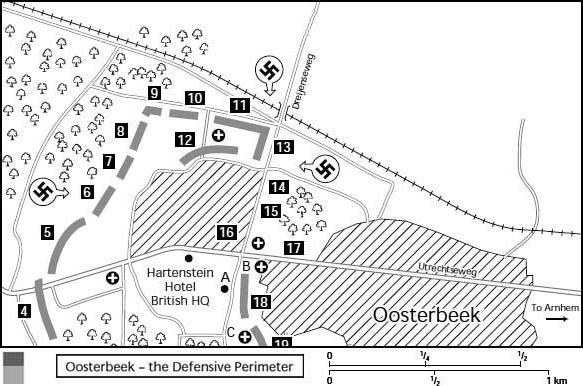

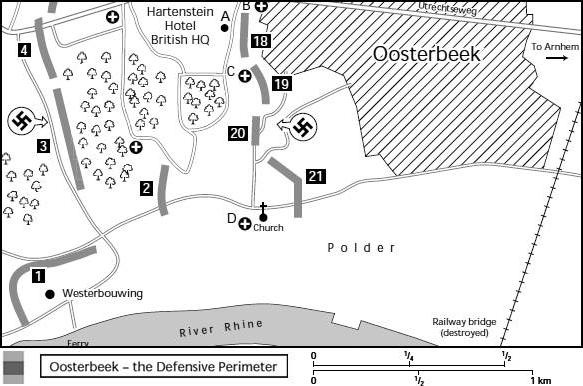

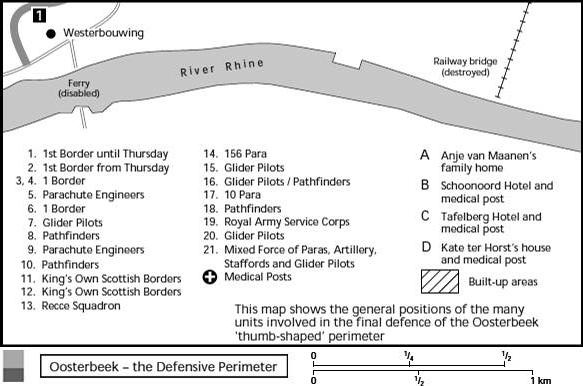

MAP 5

Oosterbeek the Defensive Perimeter

The well-manicured lawn runs down to the Thames near Abingdon. Pleasure boats cruise by and families are out enjoying the sunshine on this glorious midsummer day in tranquil southern England. But the thoughts of 89-year-old Peter Clarke whose home this is are of a different river and a different, troubled time. As he remembers faces and places, his eyes mist and he is on the banks of the Lower Rhine in the Netherlands, two thirds of a century ago. He is back among the brave and the bellicose, the wounded and the weary, the dead and the dying, in Arnhem. It was here that in September 1944 a shock force of British troops dropped from the skies into enemy-occupied Holland in what was hoped would be the decisive final battle of the Second World War. It was the most daring of raids behind German lines. If all went well, the war would be over by Christmas.

The strategy was simple enough. In an effort to speed up the defeat of Hitlers already retreating armies, twelve thousand British and Polish airborne troops flew many miles into Nazi-held Europe and descended from planes and gliders on the Dutch city of Arnhem, close to the German border, to capture and defend its vital bridge over the Rhine. Within forty-eight hours, a fast-moving column of armour from the British Second Army would arrive overland along a corridor it carved through the German lines, sweep over that bridge and on into Germany through what was in effect the open back door. That was the plan. But the mission went wrong, the reinforcements never arrived and the airborne forces were left isolated. What began as an audacious masterstroke to end the war became a desperate struggle for survival itself. Surrounded, outgunned and running out of supplies, these brave men fought for a week and more in Arnhem and in Oosterbeek, a pretty village in wooded countryside nearby.

Every street was a war zone, every stand of trees a fortress. Every inch was contested; casualties were enormous, on both sides. But in this furnace a legend was forged of bravery and endurance far beyond the simple call of duty. Even the remorseless enemy admired what the Red Devils of the Airborne Division did at Arnhem. You fought well, Tommy, many a German soldier told the six and a half thousand who were finally forced to capitulate, long past the point when they could have honourably surrendered and only when they could fight no more.

Here, in the company of the thoughtful and gentle Peter Clarke, a retired solicitor, it is a leap of the imagination to see him as a young staff sergeant fighting for his life and for those of his comrades as they huddled inside their diminishing redoubts. He is uneasy as we gently tap his memories. I remember very little of that time, nothing almost, he says at first. But its impossible to hold back the past, especially events that were so brutal and so intense, so grand in scale and yet so deeply personal that they can never be erased. There are long pauses in our conversation as if he is reloading the tape, revisiting the horrors and finding himself as affected now as he was sixty-six years ago. Everything melded into one, he says. There are no separate days, no separate nights. I dont remember morning or afternoon or evening.

The images come tumbling out. I recall a haystack that caught fire, throwing light all around the darkness and giving our position away. I was in a slit trench on the edge of a wood. There were trees behind and to the sides but in front it was wide open. I felt completely vulnerable. And then the German mortars were screaming in and all you can do is crouch down in your dug-out and hope and pray. Oh, I was scared when they were mortaring us. I remember my knees knocking. Youre under constant attack. I dont remember any times of respite. But we just got on with it. There were no orders, there was nobody running from trench to trench saying do this, look in this direction. You were out there on your own, you made your own rules, you made your own decisions. And yet, for all he had to endure, he feels privileged to have played a part and to have given so much of himself for a cause he passionately believed in the defeat of Hitler and Nazism.

Time is taking its toll on his unique generation of fighting men. Ron Brooker, the same age as Peter Clarke, was a sharp-shooter in his Arnhem days. Now his eyes are dimming. I used to be quite a marksman, he laments, but I cant see a bloody thing these days. Hes a cheery soul, neighbours pop in all the time, and, as with Peter Clarke, we have to remind ourselves that this is a man who stood toe to toe with SS soldiers. This was close-quarter killing with bullet and bayonet, he says. It was brutal. I think I had every six-foot soldier in the German army coming through the windows! He draws a map of Arnhem on a scrap of paper to illustrate where he was at this moment or that. He has precious mementoes to share the letters his mother sent to him and the ones he wrote to her from a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, the War Office telegram his parents received telling them he was missing in action. As he shoves them back into a battered brown envelope, his eyes look damp with emotion.