A BLOODY

WEEK

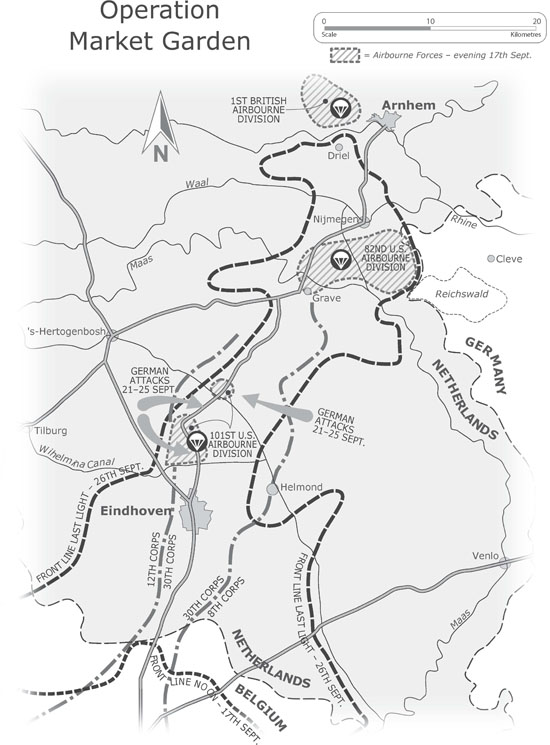

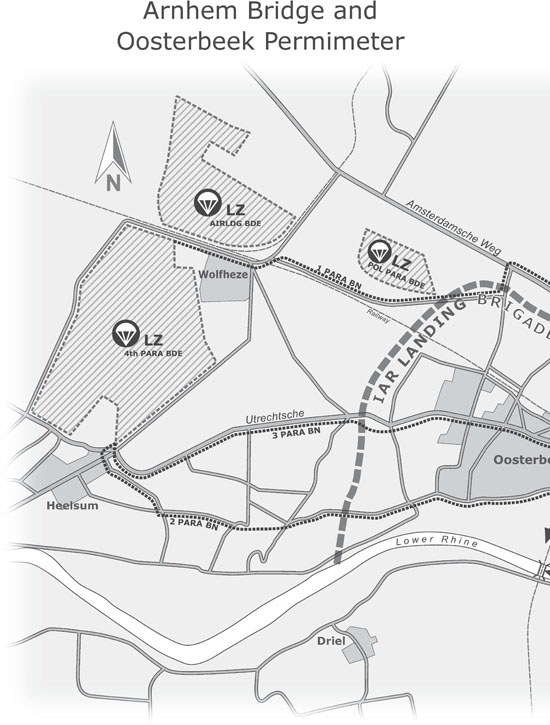

To the Arnhem Irish, both native-born and of Irish descent, whose involvement in Operation Market Garden (1726 September 1944), the largest airborne operation in history, must be acknowledged and never forgotten, and that for which they fought must not be lost.

Lieutenant Colonel Dan Harvey , now retired, served on operations at home and abroad for forty years, including tours of duty in the Middle East, Africa, the Balkans and South Caucasus, with the UN, EU, NATO PfP and OSCE. He is the author of A Bloody Dawn: The Irish At D-Day (2019); Soldiering against Subversion: The Irish Defence Forces and Internal Security During the Troubles, 19691998 (2018); Into Action: Irish Peacekeepers Under Fire, 19602014 (2017); A Bloody Day: The Irish at Waterloo and A Bloody Night: The Irish at Rorkes Drift (both reissued 2017); and Soldiers of the Short Grass: A History of the Curragh Camp (2016).

IN THIS SERIES

A Bloody Day: The Irish at Waterloo (2017)

A Bloody Night: The Irish at Rorkes Drift (2017)

A Bloody Dawn: The Irish at D-Day (2019)

A BLOODY

WEEK

THE IRISH AT ARNHEM

D AN H ARVEY

First published in 2019 by

Merrion Press

An imprint of Irish Academic Press

10 Georges Street

Newbridge

Co. Kildare

Ireland

www.merrionpress.ie

Dan Harvey, 2019

9781785372735 (Paper)

9781785372742 (Kindle)

9781785372759 (Epub)

9781785372766 (PDF)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved alone, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Typeset in Bembo MT Std 11/15 pt

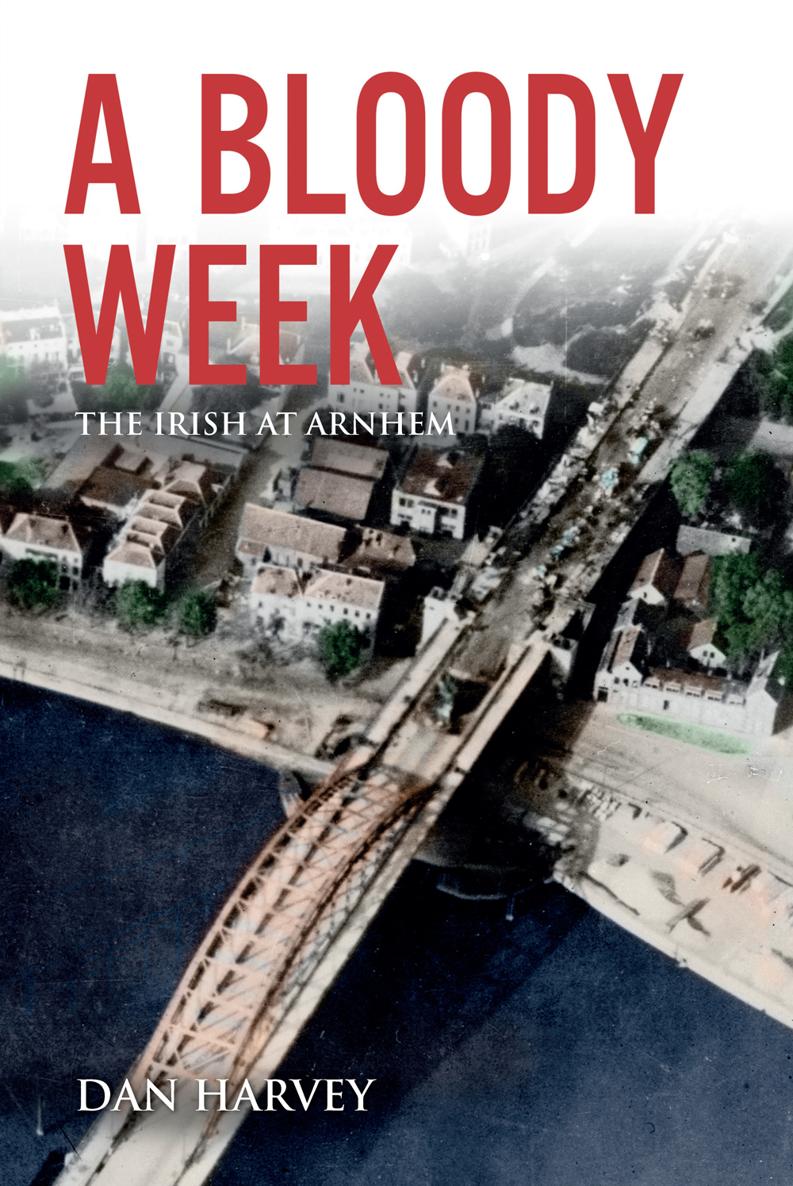

Cover front: The Allied campaign in North-West Europe, June 1944May 1945: the British Airborne Division at Arnhem and Oosterbeek in Holland Imperial War Museum.

Cover back: INTERFOTO/Alamy Stock Photo.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Death is always a difficult and distressing experience, but there is a sense of added sadness and loneliness when someone dies far away from home and loved ones. In wartime this tragedy is compounded when the victim of hostilities has no known grave. After the Second World War, great efforts were made to recover, identify and reinter the remains of the dead in Commonwealth War plots. Unfortunately, it was not always possible to find the bodies in order to retrieve them; perhaps the section of the battlefield on which they fell was subject to aerial bombing, artillery barrage or fire and building collapse, leaving families and loved ones wondering and the army helpless, unable to reassure them, the soldiers passing somehow lacking finality and remaining a cause of upset beyond grief a kind of suspended isolation.

Not for these families the comfort of a named cemetery and precise references of plot, row and grave number, and of course an individual headstone. Yet, memorials, monuments, statues and other objects commemorations, customs and remembrances all salute, honour and pay tribute to the wartime dead, marking their contribution and sacrifice. The occasioning of anniversaries in particular give a precise focus to our recollection of their dedication, determination, deeds and the manner of their death. To remember them evokes bittersweet emotions of both pride and pathos. Beyond the sadness, however, we value, respect and hold dear the worth of their contribution, effort and sacrifice.

In writing this book, I wish to thank the generosity of spirit of David Truesdale, whose original research he so graciously and willingly shared and whose 2002 book, Brotherhood of the Cauldron: Irishmen with the 1st Airborne Division from North Africa to Arnhem , is an important telling of the story of the Irish in Operation Market Garden. I also wish to thank Richard Doherty, whose encouragement was hugely significant, both in the early stages and throughout the writing of this book. To Conor Graham, Fiona Dunne, Keith Devereux and Maeve Convery at Irish Academic Press/Merrion Press. To Deirdre Maxwell, for the typing of the handwritten manuscript, and Paul OFlynn, for his technical assistance, I wish to express my sincere and heartfelt thanks.

PREFACE

Coming in over Arnhem in his stricken Dakota aircraft, Cork-born David Lummy Lord wondered how much longer he could keep the plane in the air. His C-47 Dakota was one of a number of Douglas aircraft of 271 Squadron, 46 Group RAF that had been hit by German ground fire, and Lords plane was forced to descend to about 500 feet, the starboard wing ablaze. An experienced pilot, Lord was able to maintain lift and keep the nose of the Dakota above the artificial horizon on his instrument panel, thus sustaining level flight. However, he and his crew were all too aware this could cease to be the case at any second, the wing might crumple under pressure and suddenly collapse, and with its disintegration flight would be impossible and they would immediately fall to earth.

Born in Cork in 1913, his father was a warrant officer in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers posted to Ireland who had married Mary Ellen, a local Cork girl. Their son, David Samuel Anthony Lord, had joined the RAF in August 1936 as an airman, rising quickly through the ranks. On becoming a Sergeant Pilot he was sent to India, and commissioned as pilot officer in May 1942 he flew over Burma in support of Operation Longcloth, Orde Wingates first Chindit expedition. During his time there he was awarded an Air Officer Commandings Commendation and a Mention in Dispatches (MID) receiving a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in July 1943. By January 1944 he had returned to the UK for service with 271 Squadron based at RAF Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, where he trained to drop paratroopers, supplies and to tow military gliders. Six months later, on the night of 56 June as part of Operation Overlord, he had dropped British airborne soldiers over Normandy to secure the flanks of the seaborne invaders on D-Day, the beginning of the great campaign to open the Second Front in the liberation of Europe, to restore freedom from Nazi fascism and make the world safe once again. Flying then as now through intense anti-aircraft fire, his Dakota was left with a hole in the rudder and damage to its elevator and hydraulics system. Over the next few weeks, he flew a series of missions to drop supplies to the Allied troops in the expanding Normandy beachhead.