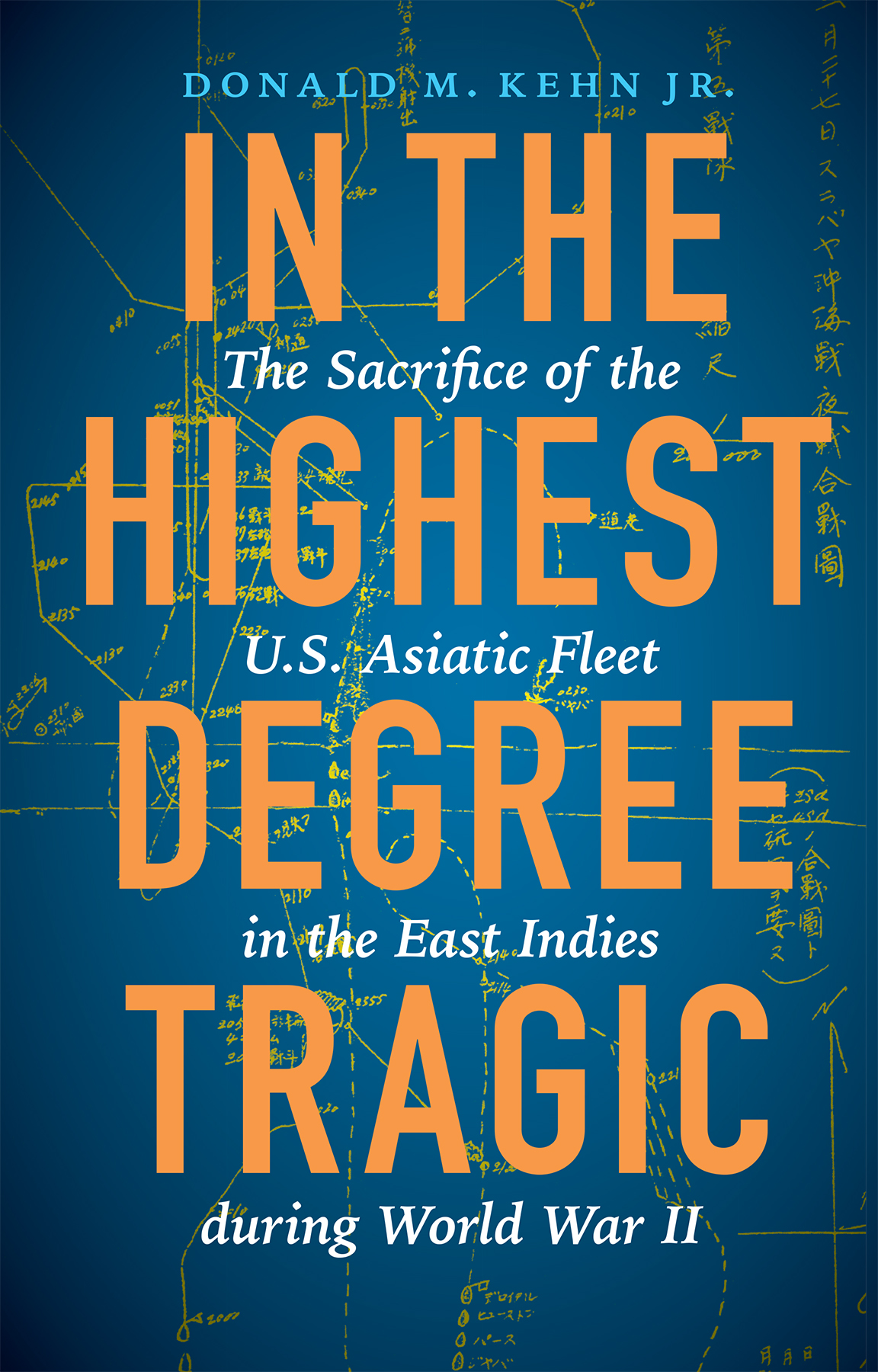

The Sacrifice of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet in the East Indies during World War II

Donald M. Kehn Jr.

2017 by Donald M. Kehn Jr.

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image is from the interior.

Parts of this book have previously appeared in different form in Donald M. Kehn Jr., with Anthony P. Tully, Drowned in Mystery, America in World War II, August 2013; and Donald M. Kehn Jr., Old Ships Turn the Tide, America in World War II, October 2014.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The story of the destruction of the old U.S. Asiatic Fleet in defense of the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) in early 1942 is one of multifaceted tragedy. Men and ships were squandered not only for questionable military purposes but, worse, as political gestures to uncertain allies. How and why this small, outdated American force should have been offered up as a sacrifice is the basis for this book.

The need for such a history is obvious enough. Although the campaign took place over seventy years ago, and a number of works have been published that purport to cover it entirely, not one has done a job of exceptional accuracy. The cause for this is twofold. First, few have had adequate access to primary Japanese military records or personal memoirs of the East Indies operations. Second, telling the truth about the backbiting within the joint command known as ABDA has been an undesirable endeavor. Our need for allies in Western Europe during the Cold War saw to that. Both of these inhibiting factors have been addressed and rectified in this work.

American history as written, published, and taught for over seven decades in the United States has also failed to properly comprehend the bravery and dedication to duty shown by its own fighting men in the Java campaign. Most histories of the Pacific Wareven nowleapfrog from the attacks on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 to the Doolittle Raid of April 1942 or the Battle of the Coral Sea that May, with no mention of the fight for the East Indies or the wasting of the Asiatic Fleet. As an Asiatic Fleet officer who was there observed later, the campaign was a peripheral affair and one in which we did not triumph. These factors were thought to explain official and unofficial willingness to overlook combat operations in the East Indies.

Be that as it may, ones patience is taxed by the nonrecognition and ignorance still persisting for those men and the lonely struggle in which they found themselves enmeshed at the beginning of the Pacific War. The narrative history that follows, then, will show the extent to which sailors and officers of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet carried out their challenging, often harrowing, tasks in the opening months of the war. It contains first-person accounts and anecdotes, from the highest command echelons down to the lowest enlisted personnel, never seen in any published books or Internet sources. And to make perfectly clear: this work does not detail the air war in the East Indies or Allied small craft or submarine operations. So while it utilizes many previously unused primary records, it is not a battle history of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the Royal Netherlands Navy, the Royal Australian Navy, or Britains Royal Navy. This narrative concentrates on the men and actions of the surface forces of the United States Asiatic Fleet.

It is therefore only fitting here to include a few comments from American participants. Adm. Thomas Hart, final head of the Asiatic Fleetand in effect its Fabius Maximuslater wrote: The men of the entire Asiatic command were splendid. They must have realized fairly early on what the outcome of the campaign would be. But, like their officers, they never faltered and kept their fighting edge to the end.

In his own Supplementary Narrative written some years after the war, Harts successor, Vice Adm. William Glassford Jr., observed:

It should also be recalled that the Force enjoyed no reinforcement, no replacement of ammunition or torpedoes and no replenishment of stores or supplies of any kind, until after the conclusion of the campaign for the defense of the Malay Barrier. We subsisted as best we could on what could be had locally. As ammunition, torpedoes, and even later, fuel, food supplies, and stores were expended, it became necessary to redistribute what remained on board the surviving ships in order to carry on. There was, however, no dearth of splendid personnel.... It should be noted here again, for the record, that this personnel, all of the regular service, acted and reacted in general magnificently throughout.

For final comments, here are remarks by two enlisted destroyermen, from USS Peary ( DD -226) and USS Whipple ( DD -217).

Peary had arguably the worst misfortune of any of the DesRon 29 destroyers. Badly damaged by bombs in the Cavite Navy Yard two days after Pearl Harbor, she and her crew underwent a miserable ordeal escaping the Philippines. The definition of a hard-luck ship, Peary was then sunk only a few weeks later at Darwin when that northern Australian port was devastated by a massive Japanese air raid. Whipple in contrast was a remarkably fortunate ship. She and her men escaped the campaign, although severely battered. And while these sailors remarks may be those of an earlier, less technologically advanced generation than ours, they are a generation over which we have no moral prerogatives. Quite the contrary.

Billy E. Green, S 1/c, operated Pearys sonar when not manning one of the destroyers .50 cal. machine guns. He was lost overboard during the ships run south when it was attacked and damaged by a trio of confused Australian bombers off Menado, Celebes (Sulawesi today)one more accidental encounter that the meager Allied forces could scarcely afford. Green would eventually become a POW on Celebes, and there he remained throughout the war.

Many years later he wrote: I realize most people relate to the cry Pearl but no one seems to ever remember the cry Manila or the forgotten (so-called) Asiatic Fleet of the U.S. Navy. I remember reading the story of David and Goliath in my pre-teens. I think I know how David must have felt when they pushed him out in front of Goliath. I would have settled for a good old fashioned Sling because our worn out old gear was not meant to fight a modern equipped invader