For my mother and father

In Memory Of: Americas service members killed in action during the Iraq War, especially the men of 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment/2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division deployed to Mahmudiyah, Yusufiyah, and Lutufiyah, Iraq, 20052006. First Lieutenant Garrison Avery, 23, Lincoln, Nebraska

Specialist David Babineau, 25, Springfield, Massachusetts

Specialist Ethan Biggers, 22, Beavercreek, Ohio

First Lieutenant Benjamin Britt, 24, Wheeler, Texas

Specialist Marlon Bustamante, 25, Corona, New York

Sergeant Kenith Casica, 32, Virginia Beach, Virginia

Staff Sergeant Jason Fegler, 24, Virginia Beach, Virginia

Sergeant Matthew Hunter, 31, Valley Grove, West Virginia

Private First Class Brian Kubik, 20, Harker Heights, Texas

Specialist William Lopez-Feliciano, 33, Quebradillas, Puerto Rico

Private First Class Tyler MacKenzie, 20, Evans, Colorado

Staff Sergeant Johnnie Mason, 32, Rio Vista, Texas

Private First Class Kristian Menchaca, 23, San Marcos, Texas

Specialist Joshua Munger, 22, Maysville, Missouri

Staff Sergeant Travis Nelson, 41, Anniston, Alabama

Specialist Anthony Chad Owens, 21, Conway, South Carolina

Captain Blake Russell, 35, Fort Worth, Texas

Specialist Benjamin Smith, 21, Hudson, Wisconsin

Private First Class Thomas Tucker, 25, Madras, Oregon

Private First Class Caesar Viglienzone, 21, Santa Rosa, California

Specialist Andrew Waits, 23, Waterford, Michigan The innocent victims of the Iraq War, especially the Rashid al-Janabi family, Yusufiyah, Iraq. March 12, 2006. Qassim Hamzah Rashid al-Janabi

Fakhriah Taha Mahsin Moussa al-Janabi

Abeer Qassim Hamzah Rashid al-Janabi

Hadeel Qassim Hamzah Rashid al-Janabi

Compassion is of value and enriches our life only when compassion is severe, which is to say when we can perceive everything that is good and bad about a character but are still able to feel that the sum of us as human beings is probably a little more good than awful. In any case, good or bad, it reminds us that life is like a gladiators arena for the soul and so we can feel strengthened by those who endure, and feel awe and pity for those who do not. Norman Mailer

CONTENTS

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

15:

16:

17:

18:

19:

20:

21:

22:

23:

24:

25:

26:

27:

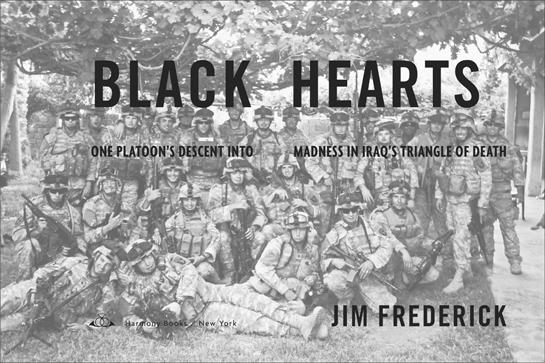

FOREWORD I N LATE S EPTEMBER 2008, CBSs 60 Minutes aired a profile of U.S. Army general Ray Odierno, who, along with General David Petraeus, is credited with spearheading a new strategy that helped bring a dramatic decrease in violence to Iraq in 2007 and 2008. During that segment, he and correspondent Lesley Stahl walked around the marketplace of a town south of Baghdad called Mahmudiyah, one of the three corners of an area known as the Triangle of Death. As they walked and talkedneither, conspicuously, was wearing a helmetOdierno told Stahl that the area was once occupied by just 1,000 U.S. soldiers, who coped with more than a hundred attacks against them and Iraqi civilians each week. Today, including Iraqi security forces, Odierno said, the region is patrolled by 30,000 men and experiences only two attacks per week. (That comparatively low level of violence held well into late 2009.)This book is about the soldiers deployed to that area back when the Triangle of Death lived up to its name, when it was arguably the countrys most dangerous region, at arguably its most dangerous time.I first became interested in 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division just after June 16, 2006. Working as Time magazines Tokyo bureau chief, I read a news report about three soldiers who had been overrun by insurgents at a remote checkpoint just southwest of Mahmudiyah. One trooper was dead on the scene and two were missing, presumed taken hostage. It was a gut-wrenching story, inviting horrible thoughts about what torture and desecration terrorists could inflict on captive soldiers. News of the search played out over the next few days, and on the 19th, the bodies were found, indeed mutilated, beheaded, burned, and booby-trapped with explosives.About two weeks after that, another story from Iraq caught my eye. Four U.S. soldiers had been implicated in the March 2006 rape of a fourteen-year-old Iraqi girl, killing her, her parents, and her six-year-old sister. The crime was horrific and cold-blooded. The fourteen-year-old had been triply defiled: raped, murdered, and burned to a blackened char. The soldiers unit: 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. Because I followed both stories somewhat distractedly at first, it took a while for me to piece together that the accused were not just from the same company as the soldiers whod been ambushed several weeks prior but from the very same platoon: 1st Platoon, Bravo Company.Two of the most notorious events from the war had flooded the headlines within days of each other, and they had happened within the same circle of approximately thirty-five men. What could possibly have been going on in that platoon? Were the two events related? As I was ruminating about such things, I got a call from Captain James Culp, a former infantry sergeant turned lawyer who was the Armys senior defense counsel at Camp Victory in Baghdad. He was a source for a story I had worked on a couple years back and he had since become a friend.He phoned to tell me that he had been assigned to defend one of the soldiers accused of the rape-murders, and he implored me to look into Bravo Company, if not for the sake of my client, he said, then for the sake of the other guys in Bravo. He told me that he had been down to Mahmudiyah several times examining the crime scene and interviewing dozens of members of the company. He finished that first call with a chilling assessment. America has no idea what is going on with this war, he said. Im only twenty miles away, and most of the people on Victory have no idea how bloody the fight is down there. What that company is going through, it would turn your hair white.Intrigued by what Culp told me, I tracked the trials of the accused soldiers as they wended their way to court over the next three years, either attending in person or reading the court transcripts. I contacted several men from 1st Platoon, to see if they were willing to talk. Surprisingly, they were. Despondent over being judged for the actions of a criminal few in their midst, they were eager to share their stories. The tales they told were raw and harrowing. They described for me the devastating losses they had suffered (seven dead in their platoon alone), the nearly daily roadside bombs called IEDs (improvised explosive devices) they had experienced, the frequent firefights they had fought, their belief that the chain of command had abandoned them, and the medical and psychological problems they were coping with to this day.They were generous with their time, unvarnished in their honesty. They suggested I widen my scope, arguing that I could not properly understand the crime and the abduction if I did not understand their whole deployment, and I could not understand 1st Platoon if I did not understand 2nd and 3rd Platoons, who had labored under exactly the same conditions but who had come home with far fewer losses and their sense of brotherhood and accomplishment more intact. Check it out, they suggested, it might lead you someplace interesting about how the whole thing went down.I followed their advice, interviewing more soldiers from all of Bravo and requesting reams of documents through the Freedom of Information Act. Embedded with the Army in mid-2008, I traveled throughout 1st Battalions old area of operations in Iraq, speaking to as many locals as I could. I interviewed the immediate relatives of the murdered Iraqi family.Every opened door led to a new one. Most soldiers and officers I talked to offered to put me in touch with more. Some shared journals, letters and e-mails, photos, or classified reports and investigations. I interviewed scores more servicemen, crisscrossing the United States several times, and ultimately broadened my scope even further to encompass not just Bravo but, for context, the rest of 1st Battalion.The story of 1st Platoons 20052006 deployment to the Triangle of Death is both epic and tragic. It was an ill-starred tour, where nearly everything that could go wrong did, and a chain of events unfolded that seems inevitable and inexorable yet, in retrospect, also heartbreakingly preventable at literally dozens of junctures.To some degree, the travails of Bravo Company are a study of the tactical consequences that flow from a flawed strategy. Their tour was part of the final deployments before counterinsurgency theory and tactics took hold, before the surge of 2007, before the cease-fires initiated by Muqtada al-Sadrs Mahdi Army became more or less permanent, before the Sons of Iraq program that paid insurgents to stop fighting Americans and start taking responsibility for their own neighborhood safety.Virtually ignored by military planners before the summer of 2005, the 330-square-mile region south of Baghdad that encompassed the Triangle of Death had become one of the most restive hotbeds of insurgency in the country, a battleground of the incipient civil war between Sunnis and Shiites, as well as a way station for terrorists of every allegiance ferrying men, weapons, and money into the capital.With far fewer troops and resources than were necessary for the job, the 1-502nd Infantry Regiment was flung out there with orders, essentially, to save the day. A light infantry battalion of about 700 men, the 1-502nd was assigned to root out insurgent strongholds, promote social and municipal revival, and train the local Iraqi Army battalions into a competent fighting force.It was a mission easy to encapsulate, but depressingly difficult to achieve. There was no coherent strategy for how they were supposed to accomplish these feats. There was confusion about whether they should emphasize hunting and killing insurgents or winning the support of the people who were providing both passive and active assistance to the terrorists. This confusion flowed from the Pentagon, through the battalions chain of command, all the way down to the soldiers. The 1-502nd arrived when Americas prospects in the country were dim, and, despite some successes in certain areas, the situation was dispiritingly bleaker when they left, with insurgent attacks on the rise and the country threatening to come apart entirely.The Triangle of Death was a meat grinder, churning out daily doses of carnage. During their year-long deployment, soldiers from the battalion either found or got hit by nearly nine hundred roadside IEDs. They were shelled or mortared almost every day and took fire from rifles, machine guns, or rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) nearly every other day. Twenty-one men from the battalion were killed and scores more were wounded badly enough to be evacuated home.The gore was unrelenting, not just for soldiers but also for civilians. Including Iraqi locals, just one of the battalions three bases treated an average of three or four trauma cases each day. Every soldier has stories of getting hit by IEDs. Many could tell of getting hit by several IED explosions in one day. The unrelenting combat wore on their psychological health. More than 40 percent of the battalion were treated for mental or emotional anxiety while in country, and many have since been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder or traumatic brain injury, or both.Bravo was particularly hard-hit. Within Bravos first ninety days in theater, all three of its platoon leaders, its first sergeant, a squad leader, and a team leader (in addition to several riflemen) had been wiped from the battlefield by death or injury. For 1st Battalion executive officer Major Fred Wintrich, the challenge doesnt get any starker: How do you reseed a company with almost all of its top leadership while in a combat zone? That was the task. By the end of the deployment, 51 of Bravos approximately 135 soldiers had been killed, wounded, or moved to another unit.Human organizations are flawed because humans are flawed. Even with the best intentions, men make errors in judgment and initiate courses of action that are counterproductive to their self-interest or the completion of the mission. In a combat zone, ranks as low as staff sergeants make dozens of decisions every day, each with a direct impact on the potential safety and well-being of their men. A company commander or a battalion commander may make hundreds of such decisions a day. Fortunately, in complex environments, individual errors or even long chains of mistakes can often be corrected or they simply dissipate before they cause any adverse effect. Decisions from different people about the same goal either negate or reinforce each other, and, it is hoped, the preponderance of these heaped-together decisions pushes the task toward completion rather than failure. But sometimes, in the permutations of millions of decisions from thousands of actors converging on a battlefield over a period of weeks or even months, a singular combination comes together to unlock something abhorrent. These are what are known, in retrospect, as disasters waiting to happen.March 12, 2006, was one such disaster. Nothing can absolve James Barker, Paul Cortez, Steven Green, and Jesse Spielman from the personal responsibility that is theirs, and theirs alone, for the rape of Abeer Qassim Hamzah Rashid al-Janabi, her vicious murder, and the wanton destruction of her family. It is one of the most nefarious war crimes known to be perpetrated by U.S. soldiers in any erasingularly heinous not just for its savagery but also because it was so calculated, premeditated, and methodical. But leading up to that day, a litany of miscommunications, organizational snafus, lapses in leadership, and ignored warning signs up and down the chain of command all contributed to the creation of an environment where it was possible for such a crime to take place.I have sympathy for the many men of Bravo who simply want this episode to go away, who saw my inquiries as a continuation of a nightmare from which they have not been allowed to wake. Several times one or the other of them remarked to me, No matter how screwed up the chain of command was, how strung out the men were, and how many risks the unit was taking, it was not so different from what happens all the time in the Army, and if March 12 hadnt happened, you wouldnt be here now, years later, in my living room, dredging it all up again. This is undoubtedly true, but there is a circularity to this logic: If something exceptional hadnt taken place, you wouldnt find it exceptional. When the final variables clicked into placean unsupervised foursome of men drunk and in a murderous mood on the afternoon of March 12the unexceptional became exceptional, and the exceptional became history.On several levels, the story of Bravo is timeless and could emerge from any war. It is about the heroic and horrible things that men do under the extreme stresses of combat. It is about men who fight despite their fear, who violently extinguish other peoples lives, who watch the best friends they will ever have die before their eyes, who make decisions under conditions that most people can barely conceive of, who butt heads with their superiors and their subordinates, and who love some of their closest comrades in arms as intensely as they do any blood relative.But Bravos story is also inseparable from the buildup to March 12, the crimes committed that afternoon, and their aftermath, which still reverberate today. It is a story about how fragile the values that the U.S. military, and all Americans, consider bedrock really are, how easily morals can be defiled, integrity abandoned, character undone.Not surprisingly, this deployment has produced deep, irreconcilable rifts between many of the men who served together. Especially within Bravo Company, and especially within 1st Platoon, the anger and bitterness that many of the men feel is difficult to overstate. When the abduction and the rape-murders became public in such close succession, the unit descended into a frenzy of finger-pointing. Seemingly everyone tried to pin a single, unified blame on a select few (and who was blamed depended on who was doing the blaming) while scrambling to absolve himself completely.I had thought that the Army way was for everyone to accept a small piece of the responsibility for any debacle truly too big to be of any one persons making and spread the blame to all parties, which would not only make it easier for everyone to survive professionally but, perhaps more important, also make the fiasco something that the Army could study and learn from. But the ordeal generated so much bile and rancor for so many people that the Army seems more interested in forgetting about the tragedy entirely than in ensuring it never happens again.Careers were ruined. Reputations tarnished. Medals withheld. Friendships broken. Prodigious resentments have festered because many men feel that blame was unfairly pushed down to the lower ranks and not shared by a higher command they believe was also culpable.This is true. The events surrounding Bravo Company were so complex and intertwined that to lay all responsibility not for the crime, but for creating an atmosphere where the crime could occur, at the feet of the few and relatively powerless, is the very definition of scapegoating. And to assert that the battalion command climate was anything other than utterly dysfunctional, or to declare that the soldiers of 1st Platoon were, at any point in the deployment, being effectively managed and led, is simply a whitewash. The Army failed 1st Platoon time and time again.It bears emphasizing that given the strain inherent in the eight and a half straight years it has been at war, the United States Army today is among the most-tested and best-behaved fighting forces in history. Rape and murder have been by-products of warfare since the beginning of time. Soldiers today, however, suffer mightily under the burden of the Greatest Generation mythos and the sanitized Hollywood depictions of World War II. There is a persistent and unfortunate sentiment among modern warriors that they will never live up to the nobility and bravery of those who saw off fascism. But anyone with a better than glossed-over understanding of the Good War knows that even Allied troops committed war crimes such as killing prisoners and raping foreign women at a rate that could be charitably called not infrequent. (One expert estimates that U.S. forces alone may have committed more than 18,000 rapes in the European theater between 1942 and 1945.) It is thus a testament to the control and discipline now exercised by the Army how rarely crimes such as this are actually committed today, and how swiftly the Army moves to investigate them.The rules of conduct have changed remarkably rapidly, as has societys tolerance for military malfeasance. Although most Vietnam War movies are works of fiction, it is fascinating how often misconduct or outright felonies figure in them, sometimes just as subplots or secondary narrative devices. In contrast, todays soldiers are required to be nothing less than warrior monks. Frequenting whorehouses and drinking anytime not on duty (and sometimes when on duty) in a war zone used to be tolerated, if not condoned, by the Army until just a few decades ago. Today, young men are expected to fight for months on end with zero sexual release and almost no social recreation whatsoever. The two-cans-of-beer-a-day ration is long gone, and even the possession of pornography is expressly forbidden.This is as it must be, of course. The story of Steven Green proves that in todays media and propaganda environment, even one private with a rifle can affect the course of a war and dramatically harm Americas image abroad. Only one out-of-control platoon needs just one Steven Green and a handful of coconspirators to significantly damage the gains that a nearly thousand-strong battalion worked hard to achieve. That is why the manner that every last private is managed, every minute of every day, warrants scrutiny.Despite battalion commander Lieutenant Colonel Tom Kunks insistence that he and his chain of command practiced what he incessantly calls engaged leadership, facts demonstrate that he and his senior leaders were woefully out of touch with the realities on the ground. Despite numerous warnings, Kunk and his subordinates were either unable or unwilling to acknowledge how dire Steven Greens mental state was specifically, or how impaired 1st Platoon was generally. Kunk instead belittled 1st Platoons incapacity, told them they were wallowing in self-pity, and blamed them and their platoon-level leadership for all their problems, which, in turn, exacerbated their feelings of isolation and persecution and contributed to their downward spiral.Bravo Company commander Captain John Goodwin made several explicit requests for more troops in late 2005 and early 2006. Kunk denied them all, arguing alternately that the company had enough men but was using them inefficiently or that there were simply no troops available. Whether Kunk, or his boss, or his bosss boss could find combat power to spare is debatable. Many senior leaders say it was impossible, there were no surplus troops anywhere in theater, and they insist that an extra platoon or company cannot be generated out of thin air. Perhaps so, but when the three Bravo soldiers were captured on June 16, 2006, 8,000 soldiers were somehow mustered and flooded the area in less than seventy-two hours.As I have met and interviewed most of the soldiers and officers involved in the main arc of the events described in this book, they have become utterly, completely human in my eyes. As I have gotten to know them, it has been increasingly difficult to employ the comforting Hollywood dichotomies of good guys and bad guys, heroes and villains. I believe there were good leaders and bad leaders in this battalion, and I think the facts demonstrate who was who, but I also believe that bad leaders had good days and good leaders had bad days. While the story abounds in compelling personalities and colorful characters, they are, of course, not characters in any novelists sense. They are all, every last one of them, real people. And besides a few significant and felonious exceptions, they were all trying to do their best, making decisions on the fly and under fire, in unspeakably difficult and dangerous circumstances, for their men, their unit, and the mission.My greatest privilege of the past three years has been getting to know so many soldiers from Bravo and the rest of 1st Battalion. There are so many clichs about supporting our troops or calling every soldier who has ever donned a uniform a hero that it debases serious tribute to genuine warriors, and trivializes the terrible sacrifices that real frontline fighters make. It has been my solemn honor to have been allowed into these veterans lives and to hear their stories.They do not ask for anyones pity, but the troopers of 1st Platoon are not the same men they used to be. The majority of them are no longer in the Army. Some of them drink too much, some are in trouble with the law, some cannot hold a job, some get into frequent fistfights, some fly into storms of rage, some suffer from debilitating medical problems, and some are racked with depression, doubt, and despair. Most of them will cope and adjust, and work hard to make peace with what they have lived through, and ultimately they will be okay. But some of them will not.The trust these men have invested in me has been humbling, and in their trust I feel a massive responsibility. I believe they understood my goal when I described it to them, which is why they frequently sat with me for days on end going over every last detail, no matter how unsavory. The goal of this book is not to make soldiers look bad, but unlike many popular military histories, it does not attempt to gloss over the inherently brutal and dehumanizing institution of warfare, it does not edit out everything unflattering, let alone upsetting, and it does not seek to make soldiers or the Army look good as an unquestioned end unto itself. I have aimed, instead, to provide an unburnished look at how the soldiers of 1st Platoon and Bravo Company actually lived, fought, strived, and struggled during their 20052006 deployment to the Triangle of Death. This book is dedicated to them.

Next page