BLOOD

FEUD

Also by Lisa Alther:

Nonfiction

Kinfolks: Falling Off the Family Treethe Search for My Melungeon Ancestors

Fiction

Kinflicks

Original Sins

Other Women

Bedrock

Birdman and the Dancer

Five Minutes in Heaven

Washed in the Blood

Copyright 2012 by Lisa Alther

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Family trees designed by Sally Neale

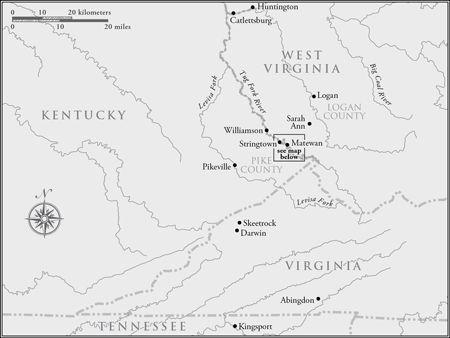

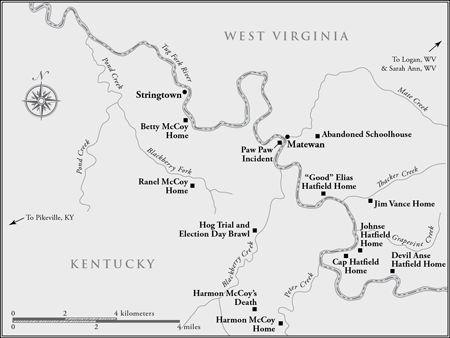

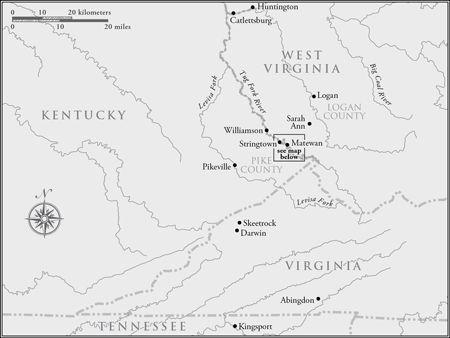

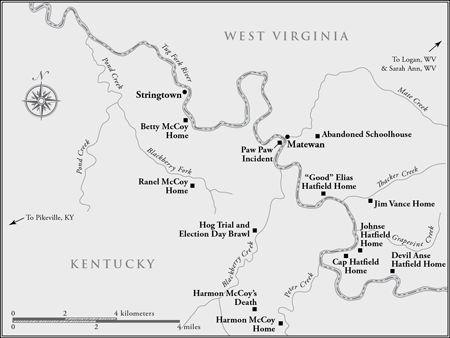

Maps by Melissa Baker Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Text design: Sheryl P. Kober

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Justin Marciano

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-7918-5

Printed in the United States of America

E-ISBN 978-0-7627-8534-6

For Ava, who inspired this project and enriches my life

The world is a stage, but the play is badly cast.

OSCAR WILDE

Murderland

I dont know when I first heard about the Hatfield-M cCoy feud; I cant recall ever not knowing about it. Nor can I remember ever being unaware of the stereotype of the hillbilly that the feud spawned: the dullard with bib overalls, messy beard, slouch hat, and bare feet, rifle in one hand and jug of moonshine in the other. This character appeared in the cartoon strips Snuffy Smith and Lil Abner, at which I chuckled every Sunday in the funny pages in my East Tennessee hometown of Kingsport. Later, once my family owned a television set, this same caricatured creature showed up on Hee Haw, The Beverly Hillbillies, The Real McCoys, and Petticoat Junction .

The Waltons and The Andy Griffith Show provided more sympathetic variations on the theme, portraying Southern mountain people as merely innocent and backward, rather than as stupid, lazy, drunk, and venalor, as one feud reporter described them: dull as death when sober and... when drunk... simply quarrelsome and murderous.

Although we lived in a river valley in the heart of the southern Appalachians, my family, friends, and I didnt think of ourselves as hillbillies. We, too, mocked the panting and the gospel music of the evangelical preachers on the radio. We worked hard to erase our accents and the dialect common to Appalachian people. We ridiculed the grammar mistakes (that I have since come to value as remnants of ancient speech patterns). Lil Abner, Snuffy Smith, John Boy, and Jed Clampett werent us. We were sophisticated, clean, well-dressed, intelligent, peace-loving, polite folks, more like Scarlett OHara and Ashley Wilkes than Daisy Mae Yokum and Jethro Bodine.

Hillbillies were the farmers who gathered downtown by the train station on Saturday mornings. They came into town in battered trucks, dressed in suit jackets, overalls, and starched white shirts. They chatted and spat tobacco juice on the sidewalk while their wives and children window-shopped at Woolworths Five and Dime. Hillbillies inhabited the shacks my family passed when we drove to our farm in the hills outside town on weekends. Hillbillies had chickens on their front porches, petunias growing in bald tires in their front yards, colored glass bottles stuck on the branches of their trees, and fighting cocks chained to blue plastic cages. Their children rolled naked in the dirt, while their menfolk, in tattered T-shirts, tinkered with the carcasses of junked cars.

But when I went to college in Massachusetts during the civil rights years and watched the racial convulsions of the Deep South, I began to realize that the mountain South differed somewhat from the plantation South. There had been slavery in the Southern mountains, but the terrain had been too rough for plantations, so those who had slaves had very few. When I was growing up, only about 7 percent of our town was black.

I began to suspect that I was not a fugitive from Tara after allI was a hillbilly. This harsh truth had been concealed from me because, according to the stereotypes in circulation, hillbillies were supposed to be quaint and impoverished rural folks. But our town was a booming industrial center where most citizens made living wages, and some did much better than that.

My grandfather and father were physicians, and my grandparents belonged to the local professional set that had sought, welcomed, and befriended industrial entrepreneurs from the North when the town was founded early in the twentieth century. Colonel Palmer from New Hampshire, who ran the Kingsport Press, lived just down the street from us, and his wife played bridge with my grandmother. So did the wife of Max Parker from Boston, who ran a textile mill. John B. Dennis, the Columbia graduate from Maine who had incorporated the town, lived just across the river from my grandparents in a mansion that had survived the Civil War. These Yankees lived large in Kingsport, like the British in India under the Raj, and my grandparents had tried to copy their example.

One summer afternoon in 2007, I attended a reunion of my fathers family, the Reeds, held at a Dunkard church in Kentucky some ten miles, as the crow flies, from the Tug Fork Valley, where the Hatfield-McCoy feud took place. After running away from his sisters farm in Virginia following the deaths of his parents when he was a boy, my grandfather Reed lived first with his older brother, Madison, on Johns Creek, just over a ridge from the Tug Fork, which separates Kentucky from West Virginia. Then he moved to his brother Roberts house, not far from this Dunkard church.

The matriarch of the Reed clan, who has organized our reunion for many years, is Ava Reed McCoy. She is the youngest daughter of my grandfathers brother Robert, a carpenter and a Dunkard preacher. Dunkard is a nickname for the Church of the Brethren, originally a German sect that based its beliefs and practices on the New Testament and especially on the Sermon on the Mount. One of the three historic peace churches, along with Quakers and Mennonites, Dunkards traditionally embrace simplicity, humility, and pacifism.

Ava is a tall, slender, handsome woman with silver hair and high cheekbones. Her father was said to have been seven feet tall, as was her uncle Madison. At just six feet four inches, my father and grandfather were the family shrimps. Ava also has the same distinctive long earlobes as my father and grandfather. My father and Ava, who hadnt known each other as children, became close friends in their later years. Each could talk to the other about long-dead relatives whom no one else still alive knew anything about.