ALSO BY MAX HASTINGS

REPORTAGE

America 1968: The Fire This Time

Ulster 1969: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland

The Battle for the Falklands (with Simon Jenkins)

BIOGRAPHY

Montrose: The Kings Champion

Yoni: Hero of Entebbe

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Going to the Wars

Editor

MILITARY HISTORY

Bomber Command

The Battle of Britain (with Len Deighton)

Das Reich

Overlord

Victory in Europe

The Korean War

Warriors: Extraordinary Tales from the Battlefield

Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 19441945

Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 194445

COUNTRYSIDE WRITING

Outside Days

Scattered Shots

Country Fair

ANTHOLOGY (Edited)

The Oxford Book of Military Anecdotes

In memory of Roy Jenkins,

and our Indian summer friendship

It may well be that the most glorious chapters of our history have yet to be written. Indeed, the very problems and dangers that encompass us and our country ought to make English men and women of this generation glad to be here at such a time. We ought to rejoice at the responsibilities with which destiny has honoured us, and be proud that we are guardians of our country in an age when her life is at stake.

Winston Spencer Churchill, April 1933

History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.

Winston Spencer Churchill, November 1940

Contents

21.

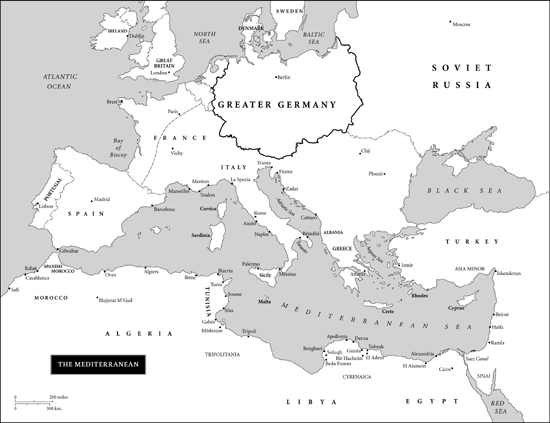

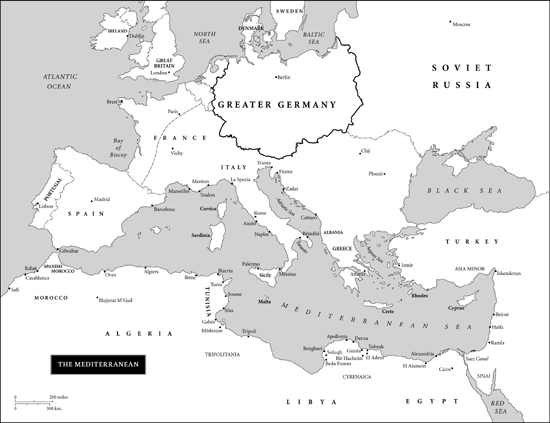

Maps

Introduction

C HURCHILL was the greatest Englishman and one of the greatest human beings of the twentieth century, indeed of all time. Yet, beyond that bald assertion, there are infinite nuances in considering his conduct of Britains war between 1940 and 1945, which is the theme of this book. It originated nine years ago, when Roy Jenkins was writing his biography of Churchill. Roy flattered me by inviting my comments on the typescript, chapter by chapter. Some of my suggestions he accepted; many he sensibly ignored. When we reached the Second World War, his patience expired. Exasperated by the profusion of my strictures, he said: Youre trying to get me to do something which you should write yourself, if you want to! By that time, his health was failing. He was impatient to finish his own book, which achieved triumphant success before his death.

In the years which followed, I thought much about Churchill and the war, mindful of some Boswellian lines about Samuel Johnson: He had once conceived of one soldier of Britains Eighth Army derived from a day in 1942 when he found the prime minister his neighbour in a North African desert latrine. Churchills speeches and writings fill many volumes.

Yet much remains opaque, because he wished it thus. Always mindful of his role as a stellar performer upon the stage of history, he became supremely so after May 10, 1940. He kept no diary because, he observed, to do so would be to expose his follies and inconsistencies to posterity. Within months of his ascent to the premiership, however, he told his staff that he had already schemed the chapters of the book which he would write as soon as the war was over. The outcome was a ruthlessly partial six-volume work which is poor history, if sometimes peerless prose. We shall never know with complete confidence what he thought about many personalitiesfor instance Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Brooke, King George VI, his Cabinet colleaguesbecause he took good care not to tell us.

Churchills wartime relationship with the British people was much more complex than is often acknowledged. Few denied his claims upon the premiership. But between the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940 and El Alamein in November 1942, not only many ordinary citizens, but also some of his closest colleagues wanted operational control of the war machine to be removed from his hands, and some other figure appointed to his role as minister of defence. It is hard to overstate the embarrassment and even shame of the British people, as they perceived the Russians playing a heroic part in the struggle against Nazism, while their own army seemed incapable of winning a battle. To understand Britains wartime experience, it appears essential to recognise, as some narratives do not, the sense of humiliation which afflicted Britain amid the failures of its soldiers, contrastedalbeit often on the basis of wildly false informationwith the achievements of Stalin.

Churchill was dismayed by the performance of the British Army, even after victories began to come at the end of 1942. Himself a hero, he expected others likewise to show themselves heroes. In 1940, the people of Britain, together with their navy and air force, wonderfully fulfilled his hopes. Thereafter, however, much of the story of Britains part in the war seems to me that of the prime minister seeking more from his nations warriors than they could deliver. The failure of the army to match the prime ministers aspirations is among the central themes of this book.

Much discussion of Britains military effort in World War II focuses upon Churchills relationship with his generals. In my view, this preoccupation is overdone. The difficulties of fighting the Germans and Japanese went much deeper than could be solved by changes of commanders. The British were beaten again and again between 1940 and 1942, and continued to suffer battlefield difficulties thereafter, in consequence of failures of tactics, weapons, equipment and culture even more significant than lack of mass or inspired leadership. The gulf between Churchillian aspiration and reality extended to the peoples of occupied Europe, hence his faith in setting Europe ablaze through the agency of Special Operations Executive, which had malign consequences that he failed to anticipate. SOE armed some occupied peoples to fight more energetically against one another in 194445 than they had done earlier against the Germans.

It is a common mistake to suppose that those who bestrode the stage during momentous times were giants, set apart from the personalities of our own humdrum society. I have argued in earlier books that we should instead see 193945 as a period when men and women not much different from ourselves strove to grapple with stresses and responsibilities which stretched their powers to the limit. Churchill was one of a tiny number of actors who proved worthy of the role in which destiny cast him. Those who worked for the prime minister, indeed the British people at war, served as a supporting cast, seeking honourably but sometimes inadequately to play their own parts in the wake of a titan.

Sir Edward Bridges, then cabinet secretary, wrote of Churchill between 1940 and 1942: Everything depended upon him

Such strictures seem otiose to those of us convinced that, in his absence, Britain would have made terms with Hitler after Dunkirk. Thereafter, beyond his domestic achievement as war leader, he performed a diplomatic role of which only he was capable: as suitor of the United States on behalf of the British nation. To fulfil this, he was obliged to overcome intense prejudices on both sides of the Atlantic. So extravagant was Churchillsand Rooseveltswartime rhetoric about the Anglo-American alliance that even today the extent of mutual suspicion and indeed dislike between the two peoples is often underestimated. The British ruling class, in particular, condescended amazingly towards Americans.