Contents

i ioo Turning Points in American History ii

iii ioo Turning Points in American History

Alan Axelrod

Guilford, Connecticut

iv

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2019 by Alan Axelrod

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-3743-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-3744-5 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

v Contents

Introduction

Arnold J. Toynbee, the twentieth centurys most famous professional historian, is widely quoted as having declared, History is just one damn thing after another. Well, the fact is that what he really did was to repeat another saying: Life is just one damn thing after another. But inasmuch as history may be interpreted as an accounting for any number of lives in the aggregate, we accept the two statements as at least roughly equivalent to one another. The point is, did Toynbee, who dedicated his own life to making sense of history, really believe either of these formulations?

It is impossible to say. What we do know is that Toynbee, like all narrative historians (as opposed to historical statisticians), translated history into stories. This is to say, he endeavored to identify and select out of the restless stream of one damn thing after another, only the very most important things.

Yet this leaves us with another question: What is a historical thing ? Is it an event? If so, what, precisely, constitutes an event ? A sequence starting with causes and ending with effects? But how to identify the causes ? And how to judge the effects ?

In the end, the narratives we call history are fictions, and the very best histories, the most compelling and revelatory histories, are the most plausible fictions. We must not mistake even the best of these narratives for objective reality.

So, is there a way of understanding the past that gets us beyond having to make up stories about things, events, causes, and effects ?

When we read a long, complex novelTolstoys War and Peace, sayor see a richly plotted movieDavid Leans classic Lawrence of Arabia comes to mindwe can struggle to remember all the names, characters, and scenes and find ourselves missing the entire experience, coming away bored and exhausted instead of stimulated and enlightened. Or we can focus on what drives the story, which is called plot, and what propels the plot, which are any number of turning points.

In history, as in a big novel or a big movie, what most compels us in the long run are not the things, events, and causes but the turning points: the decisions, acts, innovations, errors, ideas, successes, and failures on which the contours of the nations life our livesdepend. Turning points create what we call destiny or direction. They spin off our values and ideals as well as our flaws, foibles, and faults. Turning points are like the peaks of an electrocardiograman EKG. They mark the very pulse of the nations history.

This book, then, does not claim to present American History, let alone the Most Important Things, Events, and Causes in American History. Instead, it identifies one hundred points at which the national path we share turned on its way to where we find ourselves more or less in the present. If you prefer, think of these turnings as fulcrums on which the levers of national belief, effort, and endeavor lift us or let us down. In either case, they are the features of our shared story that keep us glued to the narrative, that keep us from slamming the book cover shut or taking our popcorn and walking out of the theater. They are the points, the moments, at which those who came before us could have gone this way or that. And so, we are better off knowing about them and recalling them and thinking about them than remaining unaware of them, forgetting them, or ignoring them.

Columbus Arrives in the New World (1492)

Over the past three decades or more, a laudable evolution toward increased respect for human rights has created a growing backlash against Christopher Columbus, who, upon discovering America, tried to promote to his patrons, Spains King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, the enormous value of Native American slave labor. The Spanish monarchs had authorized Columbuss voyage on April 29, 1492, the very day on which they issued their Edict of Expulsion, banishing all Jews from their kingdom. Yet, even the demonstrably intolerant Ferdinand and Isabella rejected as immoral Columbuss views on slavery. As if the modern condemnation of Columbus as a racist conquistador is not criticism enough, many commentators have long pointed out that he did not discover America at all. Nearly five hundred years before him, around 1000, Norse captain Leif Ericson, out of Greenland, struck land in present-day Newfoundland, establishing a village he called Vinland, the first European colony in North America. A few years before this, in 986, another Norseman, Bjarni Herjlfsson, became the first European to set eyes on the Americas. For that matter, geographers believe that people from Asia had entered North America as early as 10,000 bc via a land bridge that existed where the Bering Strait is now.

These criticisms and corrections matter. Yet, whether Columbus was a good man or deeply flawed and whether he discovered anything or not, he unquestionably created the first great American turning point. When, on October 12, 1492, after seventy perilous days at sea, one of his sailors sighted land, the New World began to open to the Old. The earlier migrations, sightings, and even settlements made no impact on the empires of Europe. But the impact of Columbuss first and subsequent three voyages (1492, 1493, 1498, and 1502) was profound. They began the Spanish colonization of the Americas, which was followed by the colonial projects of Portugal, England, and other European states. America rapidly entered the economic, cultural, political, and military realm of Western Civilization.

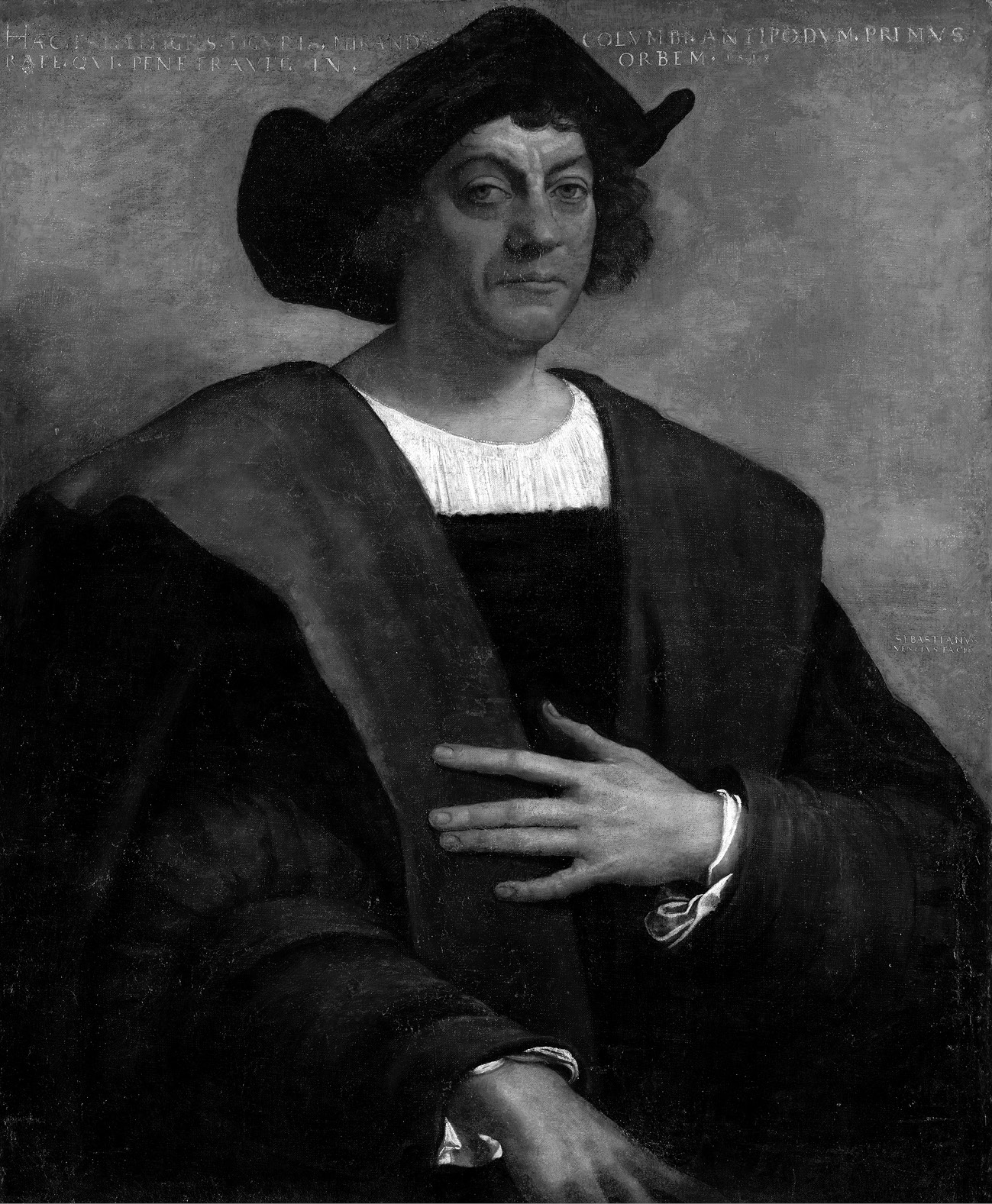

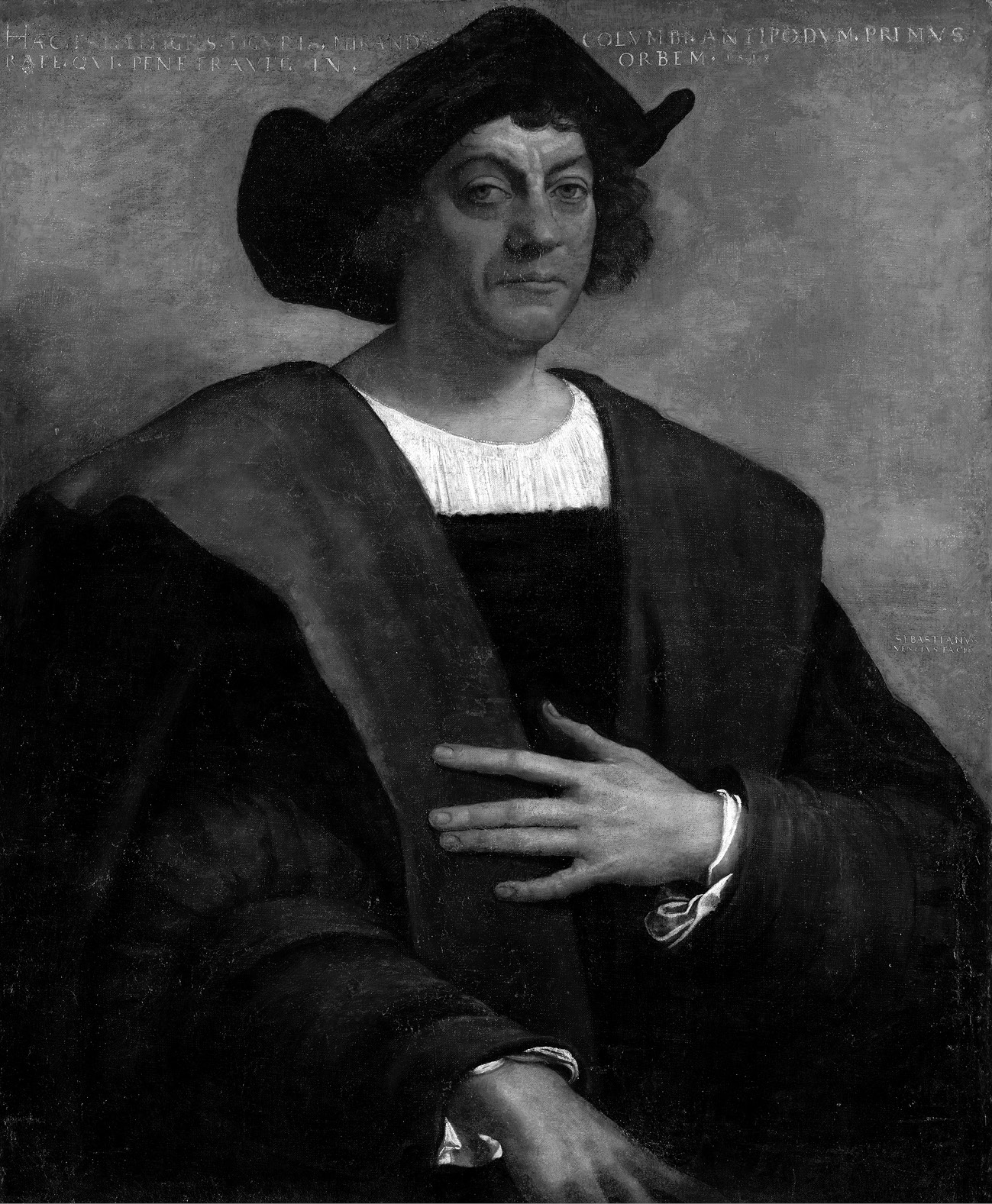

Portrait of a Man, Said to Be Christopher Columbus was painted by Sebastiano del Piombo in 1519 and today hangs in New Yorks Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Columbus was born into a family of weavers in or near Genoa about August 25, 1451. Disdaining entry into the family business, he instead went to sea some time before the 1470s. By the close of that decade, he was living in Portugal, and in 1484, he appealed to Joo II, king of his adopted country, to fund a western voyage to the island the thirteenth-century merchant-explorer Marco Polo called Cipangu (Japan). Joo was not interested.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.