Matthew Gabriele - The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe

Here you can read online Matthew Gabriele - The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2022, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- City:New York

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The beauty and levity that Perry and Gabriele have captured in this book are what I think will help it to become a standard text for general audiences for years to come.The Bright Ages is a rare thinga nuanced historical work that almost anyone can enjoy reading.Eleanor Janega, Slate

Its sweeping, its contextual, its just very light on its feet....This book is perfect for people who are interested in the period but dont know where to start. Because the scale is sweeping but so well organized....Most importantly, its really entertaining. Brandon Taylor, author of Filthy Animals and Real Life

Traveling easily through a thousand years of history, The Bright Ages reminds us society never collapsed when the Roman Empire fell, nor did the modern world did wake civilization from a thousand year hibernation. Thoroughly enjoyable, thoughtful and accessible; a fresh look on an age full of light, color, and illumination. Mike Duncan, author of Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution

A lively and magisterial popular history that refutes common misperceptions of the European Middle Ages, showing the beauty and communion that flourished alongside the dark brutalitya brilliant reflection of humanity itself.

The word medieval conjures images of the Dark Agescenturies of ignorance, superstition, stasis, savagery, and poor hygiene. But the myth of darkness obscures the truth; this was a remarkable period in human history. The Bright Ages recasts the European Middle Ages for what it was, capturing this 1,000-year era in all its complexity and fundamental humanity, bringing to light both its beauty and its horrors.

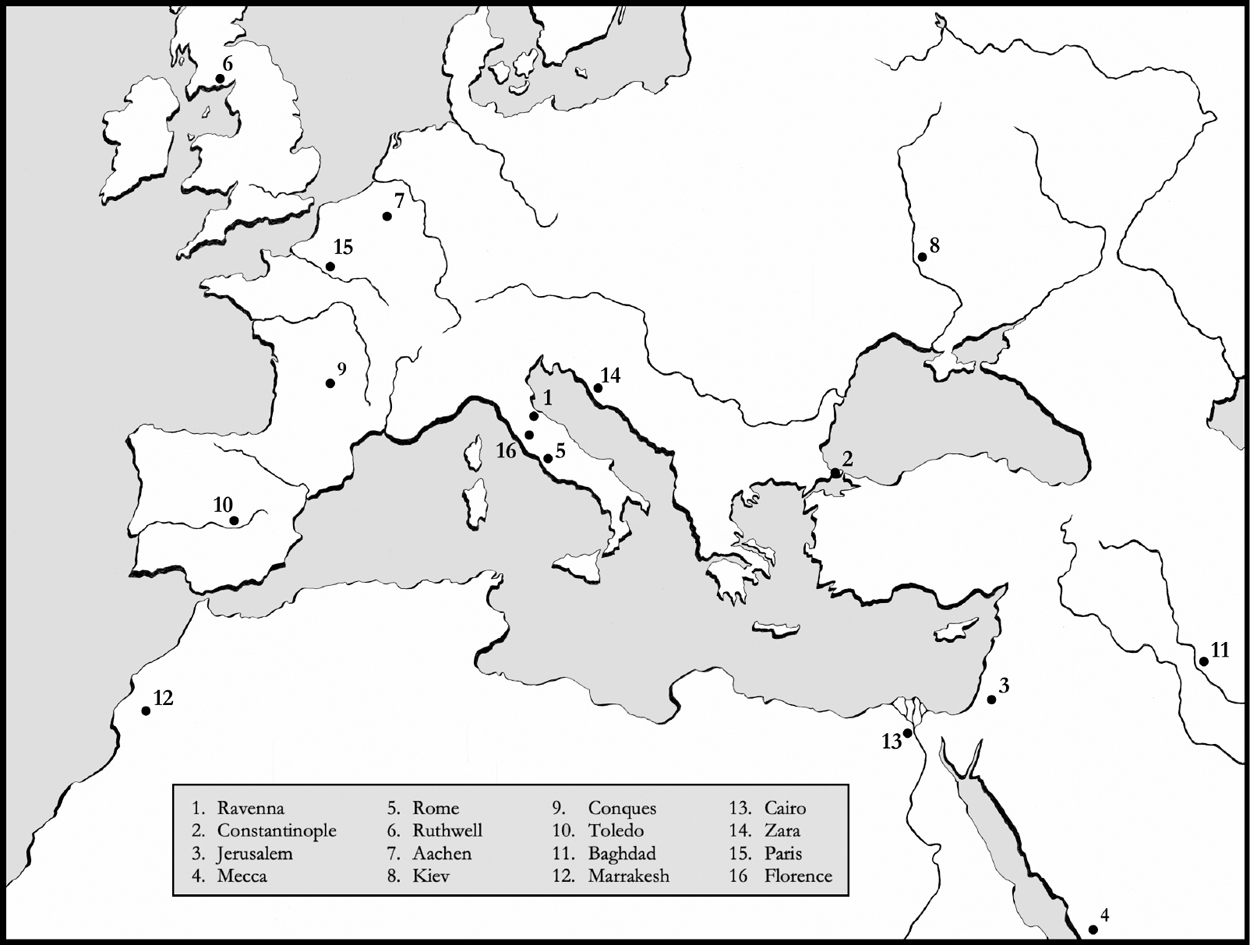

The Bright Ages takes us through ten centuries and crisscrosses Europe and the Mediterranean, Asia and Africa, revisiting familiar people and events with new light cast upon them. We look with fresh eyes on the Fall of Rome, Charlemagne, the Vikings, the Crusades, and the Black Death, but also to the multi-religious experience of Iberia, the rise of Byzantium, and the genius of Hildegard and the power of queens. We begin under a blanket of golden stars constructed by an empress with Germanic, Roman, Spanish, Byzantine, and Christian bloodlines and end nearly 1,000 years later with the poet Danteinspired by that same twinkling celestial canopywriting an epic saga of heaven and hell that endures as a masterpiece of literature today.

The Bright Ages reminds us just how permeable our manmade borders have always been and of what possible worlds the past has always made available to us. The Middle Ages may have been a world lit only by fire but it was one whose torches illuminated the magnificent rose windows of cathedrals, even as they stoked the pyres of accused heretics.

The Bright Ages contains an 8-page color insert.

Matthew Gabriele: author's other books

Who wrote The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.