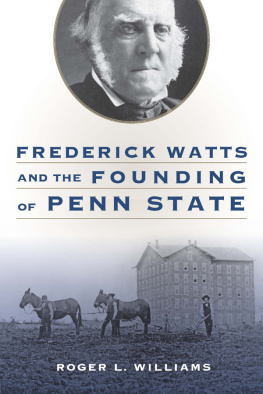

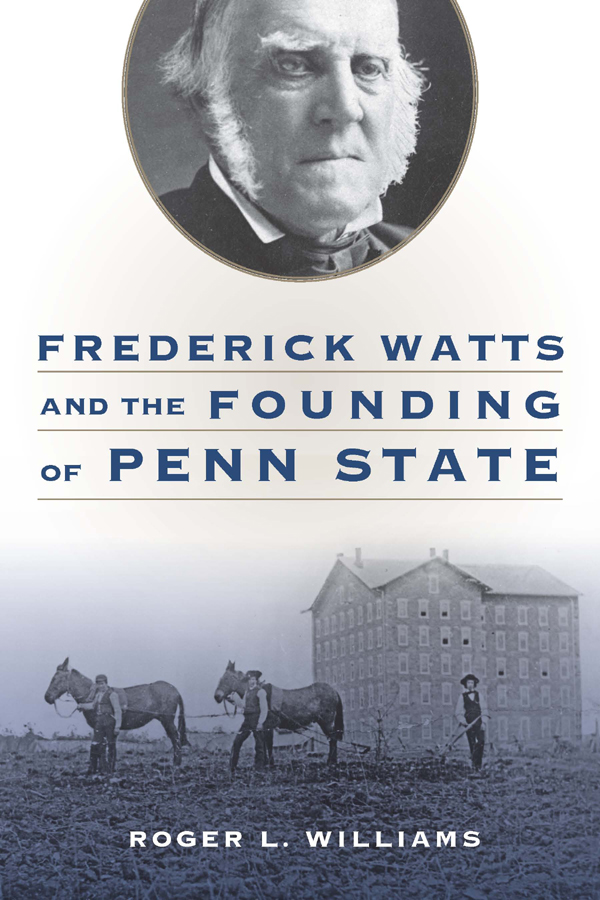

Frederick Watts and the Founding of Penn State

Frederick Watts and the Founding of Penn State

Roger L. Williams

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

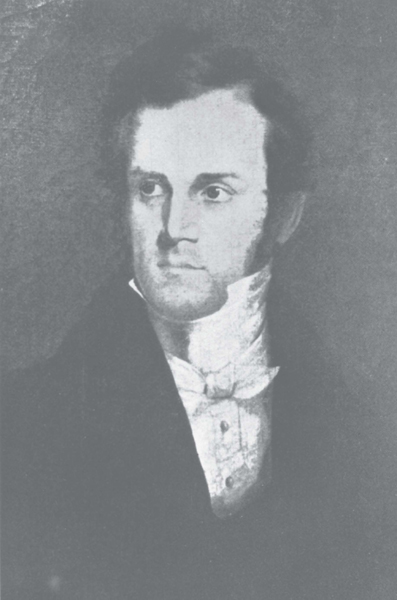

Frontispiece: Frederick Watts (180189), Carlisle, Pa., attorney and reporter for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania State University Archives.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Williams, Roger L. (Roger Lea), author.

Title: Frederick Watts and the founding of Penn State / Roger L. Williams.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Examines the life and accomplishments of Frederick Watts (18011889) in agricultural innovation and his role in the creation of the institution that would grow into Penn State UniversityProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012462 | ISBN 9780271089898 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Watts, Frederick, 18011889. | Agricultural College of PennsylvaniaHistory. | Farmers High School of PennsylvaniaHistory. | College trusteesPennsylvaniaBiography. | Agricultural innovationsPennsylvaniaHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC LD4481.P813 W378 2021 | DDC 378.1/011092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012462

Copyright 2021 Roger L. Williams

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z 39.481992.

CONTENTS

It promised to be quite a show: a crowd of five hundred to one thousand rural folk gathered in the late summer of 1840 to witness the first demonstration, in the state of Pennsylvania, of a newfangled farm machine. The impresario: Frederick Watts, age thirty-nine, prominent lawyer and reporter for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and innovative agriculturalist with an energetic drive for improving the lot of the hardworking farmer. The site: Wattss Creekside Farm, just outside of Carlisle, in the agriculturally rich Cumberland Valley of the states south-central region. The machine: the McCormick Reaper, designed by Virginian Cyrus McCormick in 1831 and patented in 1834.

Watts had publicized the event widely, but the crowd he attracted had gathered more for entertainment than edification. They had dubbed the new machine Watts Folly, and they expected an embarrassing failure. The horse-drawn McCormick Reaper had got off to a slow, uncertain start during the 1830s, because it could not handle varying conditions and was deemed unreliable. In fact, the first McCormick Reaper wasnt sold until 1840most likely to Frederick Watts.

On this day, the wheat was ripe and ready for harvest. Watts held the demonstration on a twelve-acre field that yielded about thirty-five bushels to the acrean expanse designed to put the reaper through its paces. The crowd chortled. Their moment of schadenfreude was at hand.

The demonstration began. The machine worked as intended, but the equally important human factor in the equation failed. The reaper contained a reel to tilt the wheat off the cutter bar and onto the machines platform. A man was to walk behind the reaper and rake the wheat off the platform and onto the ground, to be bound into bundles. The reaper cut the wheat quickly and perfectly, but it was blazingly apparent that the hapless raker could not keep up with the job. The crowd broke into laughter.

Then a well-dressed stranger came out of the crowd and gave some suggestions to improve the rakers performance. The reaper proceeded to move forward, but after fifty yards or so, the demonstration was halted again because the raker still could not keep up.

Finally, the third time around, the well-dressed gentleman stepped onto the machine and raked the wheat off the platform with perfect ease. This compelled the crowd to reverse its verdict and concede that the machine could work as intended. The well-dressed man then introduced himself as none other than Cyrus McCormick. The crowd not only had witnessed the first successful use of the McCormick Reaper in Pennsylvania but also, whether realizing it or not, had just witnessed a giant leap forward for American agriculture.

The demonstrations success established Wattss reputation not only as an agricultural reformer, but as a recognized leader among the independently-minded Scotch-Irish farmers of the valley.

Wattss purchase of the reaper and his inaugural demonstration were not his only contributions to Pennsylvania agriculture. The previous year, he introduced so-called Mediterranean wheat to Pennsylvania farmers. This was no small benefaction. From before the Revolution to about 1840, Pennsylvania was the largest wheat-producing state in the nation. In the years after the Revolution, however, the wheat crop was increasingly ravaged by the Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor), an invasive insect thought to have been inadvertently imported to the country via the livestock of Hessian soldiers. By 1790, the fly was causing widespread devastation, particularly in southeastern

A half century later, visiting the farm of a friend, Watts and his wife, Henrietta, learned of a new variety of wheat. As Watts told the story:

About the middle of June, 1839, near Trenton, New Jersey, I was met by a former resident of the Carlisle Barracks, Lieut. Wm. Inman, of the United States Navy, who invited us to spend the night at his home on the farm. The next day he showed me a field of beautiful wheat which was ripening for harvest. He told me that two years prior to that time he had procured three bushels of the seed near Leghorn, Italy, and was now raising the second crop. I obtained from him six barrels of the same kind and sowed it on my farm near Carlisle. That was the introduction into the United States of the beautiful variety of wheat which for a long time was very popular and was known as Mediterranean. From the six barrels which I sowed it was spread through the Cumberland Valley and into other parts of the state.

The advantage of Mediterranean wheat was that it matured early, such that it could be harvested before the hatching season of the Hessian fly. Mediterranean wheat quickly began to produce increased yields, ultimately saving the day for farmers across Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

A decade later, in the early 1850s, Frederick Watts would use his talents to save the day for Pennsylvania farmers in even more profound ways. With like-minded colleagues, he would organize the Pennsylvania farming community into the powerful Pennsylvania State Agricultural Society and serve as its founding president (1851). He wanted to bring farmers together as a self-conscious community to better their social, economic, and political lot in life. Then he would use his presidential platform to advocate urgently for the establishment of an agricultural college (1854 and 1855) that would provide a scientifically based education for farmers sons. Watts would serve as president of the board of trustees of the new Farmers High School, later renamed the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania, for nineteen years. Finally, he would cap his career by serving as U.S. commissioner of agriculture (187177), appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant.