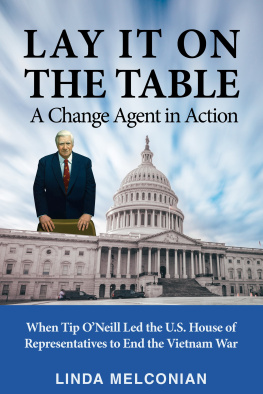

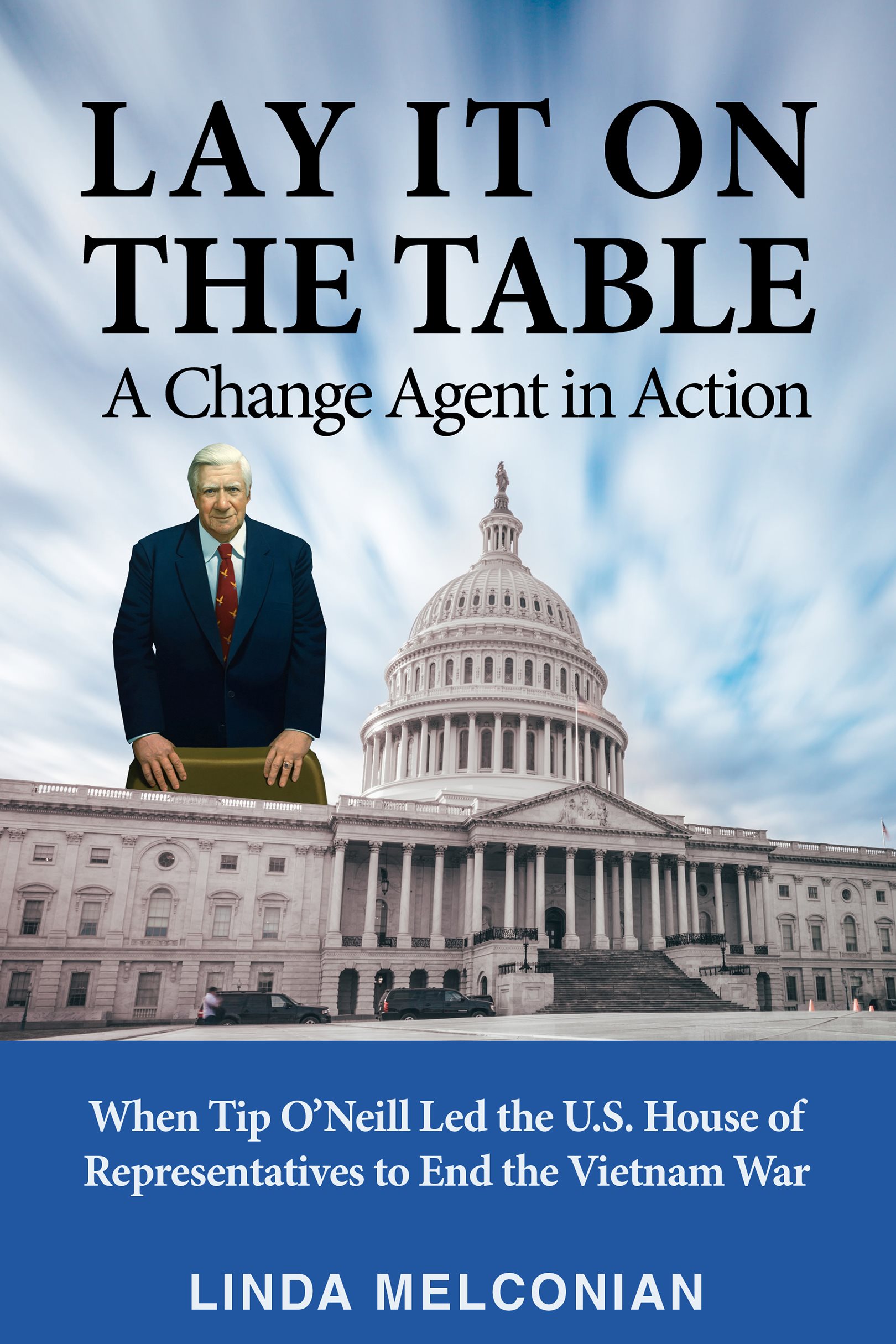

Lay It on the Table

A Change Agent in Action: When Tip ONeill Led the U.S. House of Representatives to End the Vietnam War

By

Linda J. Melconian

Lay it on the Table

A Change Agent in Action: When Tip ONeill Led the U.S. House of Representatives to End the Vietnam War

by Linda J. Melconian

Copyright 2022 Linda J. Melconian

Published by SkillBites LLC

https://skillbites.net/

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is based on the authors recollections from 50 years ago. It is intended to provide accurate information with regards to the subject matter covered. However, the Author and the Publisher accept no responsibility for inaccuracies or omissions, and the Author and Publisher specifically disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, whether personal, financial, or otherwise, that is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, from the use and/or application of any of the contents of this book.

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-1-952281-47-1

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-952281-48-8

Dedication

To my mother, Virginia Elaine (Noble) Melconian, a talented and gifted writer unrecognized in her day; and my father, George Melconian, a history buff who introduced me to politics.

Acknowledgements

This book is the result of rewriting, editing, and expanding a Masters thesis at The George Washington University, under the direction of the late Professor Ralph Purcell, to whom I am especially indebted for his keen knowledge of politics, personalities, and Capitol Hill. He furnished me with a critical evaluation of many ideas presented in the following pages. I am grateful for his careful reading of the preliminary draft of my thesis, written forty-plus years ago, and for all his thoughtful and excellent suggestions to improve the thesis.

I am deeply grateful to my Suffolk University graduate fellow, Johana Englund, for her willingness and time-consuming ability to use modern technology to digitize a type-written thesis and review and update its sources.

I want to offer a special and heartfelt thanks to Dara Powers Parker, whose patience as my development editor and manuscript coach is unsurpassed and truly commendable. For her reading and formatting my very rough drafts and providing thoughtful and intuitive suggestions to improve this historical narrative, I am grateful.

I want to thank the children of Speaker Tip ONeillRosemary, Tom, and Kipfor their helpful and thorough review of the manuscript, especially Tom and Rosemary ONeill. I am deeply humbled and thankful to Christopher Kip ONeill for his generous endorsement and insightful corrections.

I am profoundly grateful to Charlie W. Johnson, the former U.S. House parliamentarian, for his detailed and meticulous review of the parliamentary and Democratic Caucus process and procedures discussed in the manuscript and for his astute testimonial.

To Sally Donner, a fellow Mount Holyoke intern in Washington, subsequent staff assistant, and then staff director to Republican Rep. Silvio Conte (Massachusetts) during Tip ONeills tenure as Majority Whip, Majority Leader, and Speaker: I greatly appreciate her review and endorsement of the manuscript.

I thank my friend, Tom Birmingham, former President of the Massachusetts State Senate, for his willingness to read the manuscript and pen a testimonial.

I thank Nancy Diehl DiGiovanni for her reflective observations during her read of the manuscript.

Lastly, I want to thank Professor Richard Taylor, my Suffolk University colleague and former Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation, for his interest in the subject and willingness to read and offer critical comments on the manuscript.

Preface

I was a child in 1960 when John Fitzgerald Kennedy, a native son of Massachusetts, was running for president. Kennedy swung through Springfield, Massachusetts, where I grew up, for a rally just before the election. My father took me to hear the candidate speak. Being small, I was able to move in close and shake his hand. Forty-eight hours later, Kennedy was the President-elect. I didnt want to wash that hand. I kept looking at it for a whole week. My hand touched the President-elect of the United States! Even though I was only a little kid, that handshake meant something to me.

My first visit to Washington happened a few years later, during the Senate consideration of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A young teenager, I remember sitting in the Senate gallery with my parents, George and Virginia, and watching one manSenator Strom Thurmond (South Carolina)read from the phone book to a near-empty chamber. I thought, Whats this all about? Where are all the rest of the senators? Whats going on? Whats the phone book got to do with civil rights?

Then we walked over to the House gallery to watch the action in that chamber. John McCormack was the speaker then, and he was also from Massachusetts. Again, I saw one man reading to a deserted chamber, and I said, This isnt what I learned about the House in the schoolbooks.

Years later, when working in Washington, I realized what I had witnessed in that 1964 visit to the Capitol: a filibuster in the Senate and special orders in the House. The legislative process was incomprehensible yet captivating to my young, fertile mind, even though it seemed in practice at odds with the seeds of learning about how a bill became law instilled in me in the classroom.

After graduating from Springfield public schools, I was admitted to Mount Holyoke College, a historic liberal arts womens college, where I would earn my degree, cum laude, in history. While I was a student at MHC, my congressman, Edward Patrick Eddie Boland, ran for reelection in a tough primary challenge from the mayor of Springfield. That year, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara made defense cuts across the country, including closure of our own Springfield Armory, the oldest armory in the United States. General George Washington had commissioned the Springfield Armory in 1777 during the American Revolution. It made the M-14 rifles used by our military in Vietnam combat operations in the early to mid-1960s. My hometown blamed the incumbent congressman for the closure, and the campaign against him was feisty and hard-fought.

During that reelection campaign, I was a proud Boland Girl. Every Thursday evening, I joined other Boland Girls in front of Springfields two large department stores, wearing Boland hats and banners across our chests, holding placards as we walked in circles. Some of us would approach shoppers, saying, Vote for Boland! It was fun; we were engaging the public and building momentum for Bolands eventual primary victory for the 1968 election.

Those of us who grew up in the 1960s witnessed a tumultuous period in American history: weekly demonstrations against the Vietnam War, frequent marches for womens equality, Black Americans subjected to tear gas and police clubs for claiming their rights as citizens, college students demanding more love and not war. These cultural change movements piqued my interest in government and public service.

The Vietnam War was a front-and-center issue during my college years. It was an unwinnable war, even with our continued military presence, which supported a corrupt regime in the name of democracy in the cold war effort against communism. Even as college students, we knew we had to get out of that war.