Contents

Landmarks

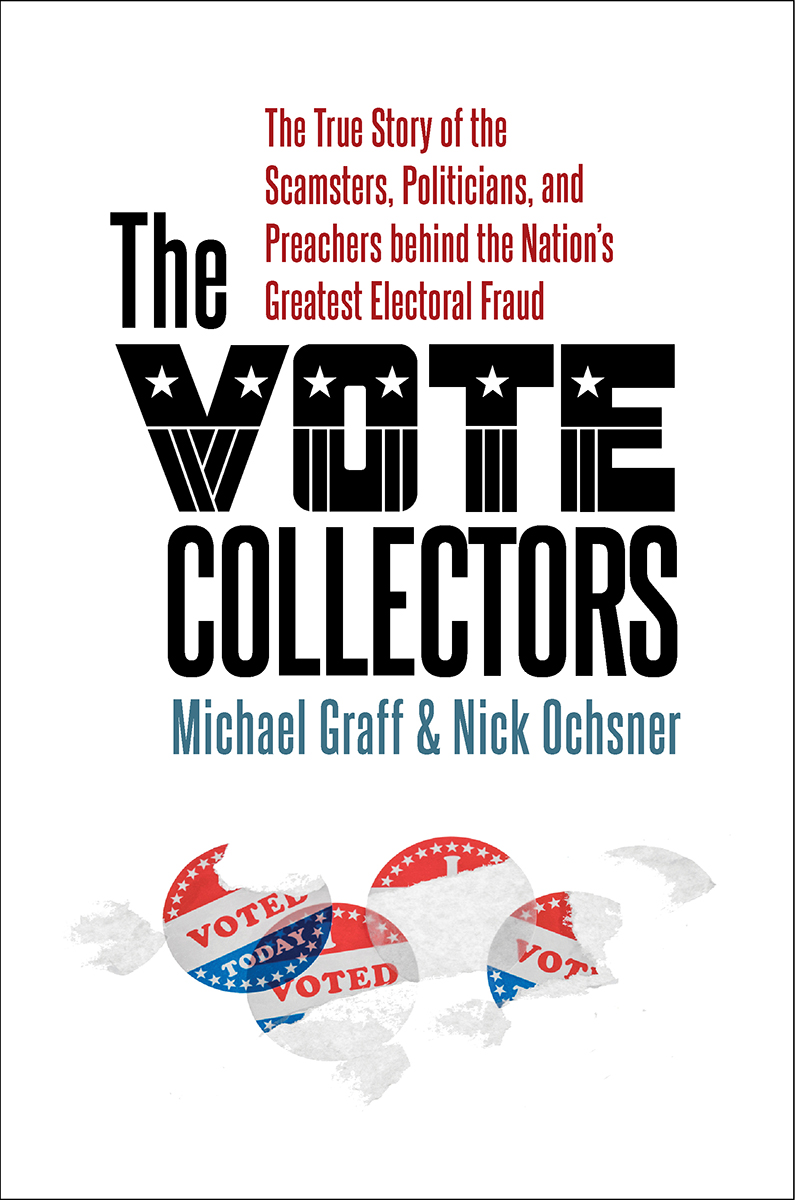

The Vote Collectors

This book was published under the

MARCIE COHEN FERRIS AND WILLIAM R. FERRIS IMPRINT

of the University of North Carolina Press.

2021 Michael Graff and Nick Ochsner

All rights reserved

Designed by Richard Hendel

Set in Utopia, Klavika, and Patriotica types

by codeMantra

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Cover image iStockphoto/BackyardProduction. Interior image of button iStockphoto/koya79.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Graff, Michael (Journalist), author. | Ochsner, Nick, author.

Title: The vote collectors : the true story of the scamsters, politicians, and preachers behind the nations greatest electoral fraud / Michael Graff, Nick Ochsner.

Other titles: Ferris and Ferris book.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2021] | Series: A Ferris and Ferris book | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021866 | ISBN 9781469665566 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469665573 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Harris, Mark, 1966 April 24 | United States. Congress. HouseElections, 2018. | Republican Party (N.C.) | ElectionsCorrupt practicesNorth CarolinaBladen County. | ElectionsNorth CarolinaHistory. | African AmericansCivil rightsNorth CarolinaHistory19th century. | North CarolinaRace relationsHistory19th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / State & Local / South (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV) | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Process / Campaigns & Elections

Classification: LCCJK1994 .G73 2021 | DDC 324.6/60975632dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021866

Contents

The Vote Collectors

Prologue Morning in Mother County December 2018

A blazing pink sky decorates the tops of flat fields along the two-lane road that leads to the town of Tar Heel. Its just before seven on a Friday morning in December 2018. The thatch remnants of whatever had been growing in late summer still lean toward the Cape Fear River, two months after Hurricane Florences floodwaters receded.

Men in jeans and flannel shirts ache and groan as they climb the steps of Tar Heel Baptist Church for the weekly Friday mens prayer breakfast. Around the low-ceilinged fellowship hall are thirty-five men of different races and political persuasions, bonding over sunrise, prayers, and bags of Hardees. Ham biscuits on the right, a man says, sausage on the left.

They talk quietly. They give firm handshakes and a few hugs. They are Black and white and Latino. Theyve been through hell with the hurricanes lately. Some lost their entire fall crop. Some might soon lose a farm. On top of that misery, theyve been made fun of all over the world.

Tar Heel, population 150, holds two distinctions: its name matches the nickname and logo of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, 115 miles to the northwest; and its the home of the Smithfield packing plant, the worlds largest hog-processing operation.

But over these few weeks in December 2018, reporters from New York and Washington have rented cars and come here to ask questions about the door-to-door ballot-collection program that upended the midterm election. Its big news elsewhere, for whatever reason small-town shit becomes big news. A congressional race got held up. Dan McCready, the boyish-looking Democrat, got close to turning a very red district blue for the first time in almost four decades. Hed lost to Mark Harris, the preacher with the good hair, by less than a thousand votes. But a month after Election Daythe week after Thanksgivingthe state board of elections said it couldnt certify the race because something was crooked with the ballots of Bladen. They said it had been going on for years and that now, after such a close election, it had to stop.

That was about a week before the prayer breakfast in the fellowship hall. In the days between, people in suits used the scandal to point fingers at other people in suits, to justify whatever political beliefs they have. The president hadnt done them any favors, tweeting out lies about Democrats and voter fraud and immigrants who cast ballots illegally. Now some people on his own side were caught, which would be bad enough even if it didnt mean that all the left-leaning news organizations in the Western Hemisphere were hitching their assumptions to the story and using it as a reason to say, See, Republicans are the cheaters!

Stephen Colbert even devoted four minutes of his monologue to the scandal around the door-to-door ballot collections here.

Theyre like Jehovahs-I-hope-there-arent-witnesses, Colbert said.

The men in the church are tired of it. Yall didnt give a damn, they keep saying to outsiders, when the chemical company an hour north contaminated the drinking water.

Didnt give a damn when water rose to the roofs of homes and businesses in the county seat during Hurricane Florence.

Didnt give a damn when hog farmers needed help defending themselves against slick Texas lawyers who filed those multimillion-dollar nuisance lawsuits on charges that hog farms stink. No shit.

But now here they were, these people from all over, giving a damn about Bladen County, North Carolina, chasing down a few scribbles on ballots and saying its the home of the biggest political story outside the Beltway.

Where, they wonder, have yall been?

To understand how election fraud happens, and how a small place like Bladen County became a siren of a fracturing democracy years ahead of the 2020 election and violent attempts to overturn it, you cant make simple assumptions. You have to understand how big-city prejudices about race and class can be flipped upside down in places like this. You have to understand that its a story about nothing and everything. You have to understand the land.

Bladen used to be the ocean floor. Millions of years ago, saltwater waves crashed against the Uwharrie Mountains, about 150 miles inland from the current Atlantic coastline. Over time the sea slipped east and left behind a grainy, sandy soil, ripe for peanuts and soybeans and longleaf pines. It left behind the coastal plain, the region of flatlands where Bladen County sits.

The ocean tells the story of the past, but also the future. A series of devastating floods have amounted to the oceans way of saying it wants to reclaim some of what it left behind.

Already some places have conceded. Way out on North Carolinas eastern elbow, the last three residents of the once-thriving maritime port Portsmouth Island left in the 1970s, mostly in response to a series of hurricanes. The only occupants left in the village now are the mosquitoes and biting flies. The federal government turned Portsmouth into a national park, with some of the softest sand youll ever encounter, and the park staff keeps up maintenance on a few cottages, an old church, and the post office. They stand there neatly still today, as if their occupants will be right back.

The closer you look at the flood maps and predictions, the more you wonder if places like Bladen County are next. What was a county with 35,000 inhabitants in 2010 now has only slightly more than 30,000 in 2020. Eastern North Carolina has a bit of a history with vanishing settlements. The first European child born in North America, Virginia Dare, was delivered on Roanoke Island here in 1587. She was part of whats still known as the Lost Colony, a group of settlers who disappeared but still live on through a glittery outdoor theater production designed by the Broadway legend William Ivey Long.