WINNING WARS AMONGST THE PEOPLE

Winning Wars amongst the People

CASE STUDIES IN ASYMMETRIC CONFLICT

PETER A. KISS

2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of

Nebraska

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the

University of Nebraska Press.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kiss, Peter A.

Winning wars amongst the people: case studies

in asymmetric conflict / Peter A. Kiss.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61234-700-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61234-703-5 (pdf) 1. Asymmetric warfareCase

studies. 2. Military history, ModernCase studies. I. Title.

U240.K523 2014

355.4'2dc23

2014001246

Set in Scala by L. Auten.

To Timi, my wife. She not only faithfully supported my efforts throughout and encouraged me when my enthusiasm begun to fade, but also provided that most valuable commoditysilencewhich is indispensable for serious study.

CONTENTS

FIGURES

TABLES

PREFACE

A Gap to Fill

This work started its life as a doctoral dissertation. The idea of eventually publishing it as a book was born quite early in the preliminary research phase, when I perceived a gap in Western professional literature. I found that nearly all international and national security documents accessible to the public, as well as most current academic analysis, treat the question of asymmetric warfare in the context either of the fight against terrorism or of expeditionary operations in the third world. This focus reflects recent European and American experience, but some clouds on the Western political horizon suggest that governments in the European Unions core areas may also face asymmetric challenges in the future. The experience their armed forces have gained in expeditionary operations will mostly be irrelevant in these conflicts; a new approach will be needed to fight fellow citizens, brothers, neighbors.

I fully acknowledge my admiration for, and my debt to, the authors who traveled this road before me. I borrowed the phrase war amongst the people from a distinguished British soldier, General Rupert Smith. I relied heavily on the works of the older classics (Callwell, Gwynn, Lawrence), the more recent classics (Trinquier, Galula, Kitson, Nasution), the moderns that are likely to become classics (Lind, Hammes, Nagl, Kilcullen), as well as the less well known professionals. I do not claim that this book is better than their worksit probably is not. I only claim that it is different both in focus and in treatment, and therefore it may be more apposite in the current (and near future) Western security environment. Its emphasis is on the special circumstances of asymmetric conflict in the domestic context. It seeks to discover those principles that would allow a Western nation to meet the challenge without outside assistance or interference and at the same time remain within the boundaries of laws and ethics, protect the nations culture, observe its values, and retain its liberties, traditions, and way of life.

Since my doctoral studies had to fit into the framework of a Hungarian universitys research program, some of the issues I address in part 3 are specifically related to the social and political environment of Hungary. These may not be familiar to the English-speaking public; therefore I expanded this chapter into a full-fledged case study.

My purpose in publishing this book was to contribute in a small measure to the ability of the Western worlds democratic governments to face the security challenges in the new international environment. The reader will decide whether I have succeeded. If I have, credit must be given to those who made it possible: the officers under whose command I was privileged to serve; the men and women I had the honor to lead; the fellow professionals I consulted; the teachers and fellow students at various military and civilian academic institutions; and of course the authors whose works I studied. If I failed, the blame lies with me alone.

Finally, a note on language. My mother tongue is Hungariana complicated language with a politically correct virtue: it has no gender. When I started learning other languages, I had to grasp three things very thoroughly: gender exists not only in biology but also in grammar; biological gender and grammatical gender do not always coincide; the general subject in a sentence usually takes the masculine or the neutral. When writing this book, I decided to keep myself to these simple rules, rather than engage in such linguistic contortions as he/she or the (surely criminal) use of they with the singular.

1

A Paradigm Shift in Warfare

Until very recently these conflicts were known as proxy wars and were seen not as a new stage in the development of warfare but as tools of superpower confrontation: Russia, the United

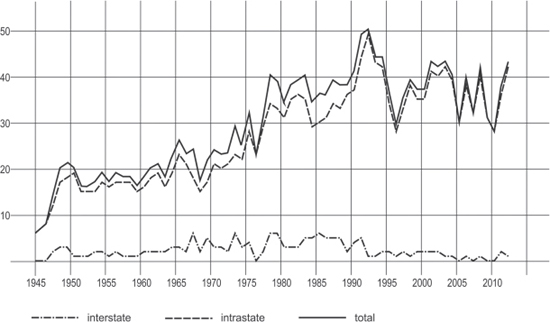

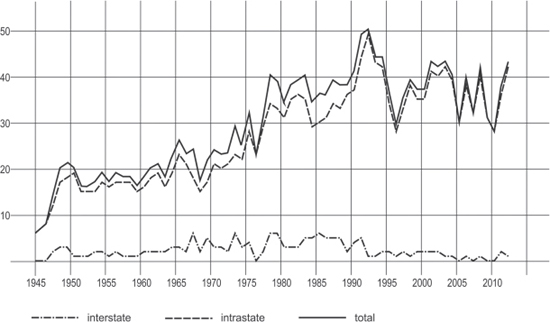

Fig. 1. High-intensity intrastate and interstate conflicts between 1945 and 2012. Based on information in J. Joseph Hewitt, Jonathan Wilkenfeld, and Ted Robert Gurr, Peace and Conflict, and Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research, Conflict Barometer.

The following three chapters provide a broad overview of this phenomenon. lays out the social, political, and economic causes of the paradigm shift and explains why asymmetric (fourth-generation) warfare has become the dominant form of armed conflict and why the forces of the modern state find it so difficult to respond to the challenge.

CHAPTER 1

Intrastate Conflict

The New Security Challenge

The Nature of the Problem

In the brave new world, where the dominant form of warfare is internal conflict, the enemy is really more of an opponent: fellow citizens who have a different vision for the future and resort to force to make society accept it. Maneuvering on the borderlines between parliamentary politics, street politics, criminal activity, and combat operations, they demand the legal protections due statesmen, political activists, criminals, or soldiers but reject the responsibilities associated with these categories. They do not wear uniforms; they hide among civilians and initiate their attacks from among civilians. They target civilians, the civilian infrastructure, and the symbols of the states power. Their goal is not to destroy the security forces but to gain control over the thinking and behavior of the people.

The international security and defense strategies as well as the national security strategies and doctrines of individual states suggest that the Wests political elites and security professionals consider such asymmetric challenges possible only in Asias and Africas unstable states. They see terrorism as the only source of danger, which is then assigned to the police to handle (perhaps with a bit of help from the armed forces).

Supranational entities, from the United Nations to regional political, military, and commercial organizations, have come into being and imposed limits on their members sovereignty. Although membership is optional in most cases (with the Warsaw Pact serving as an obvious exception), few nations decide to go it alone and forgo the substantial benefits that become available upon joining. Meanwhile, the ability of Europes nation-states to deliver the services to which their citizens have become accustomed, and their very ability to provide a secure environment are diminishing, which leads to the citizens losing confidence in their government. The rigid, confusing, and unresponsive political structure of the EU does nothing to counter this loss of confidence. These factors, combined with corrosive ideologies (multiculturalism, moral and cultural relativism, political correctness), create fertile soil for asymmetric challenges, and at the same time they reduce the states ability to respond to them. Kosovos independence (a nonstate belligerents spectacular success against the power of the state) is likely to encourage Europes minorities to seek not only autonomy, but their own independence.

Next page