Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

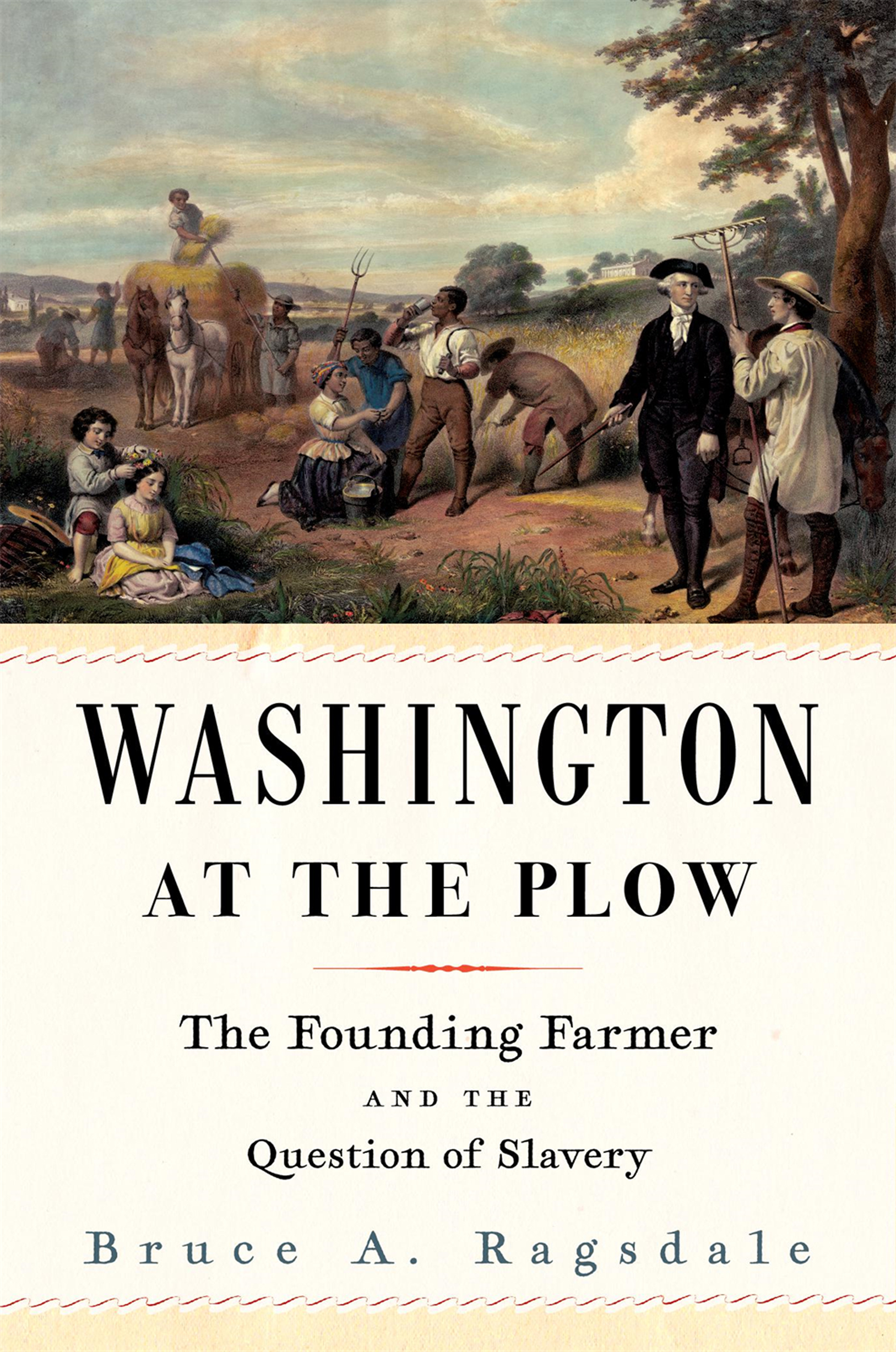

WASHINGTON

AT THE PLOW

The Founding Farmer and the Question of Slavery

BRUCE A. RAGSDALE

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS & LONDON, ENGLAND2021

Copyright 2021 by Bruce A. Ragsdale

All rights reserved

Jacket Design by Marina Drukman

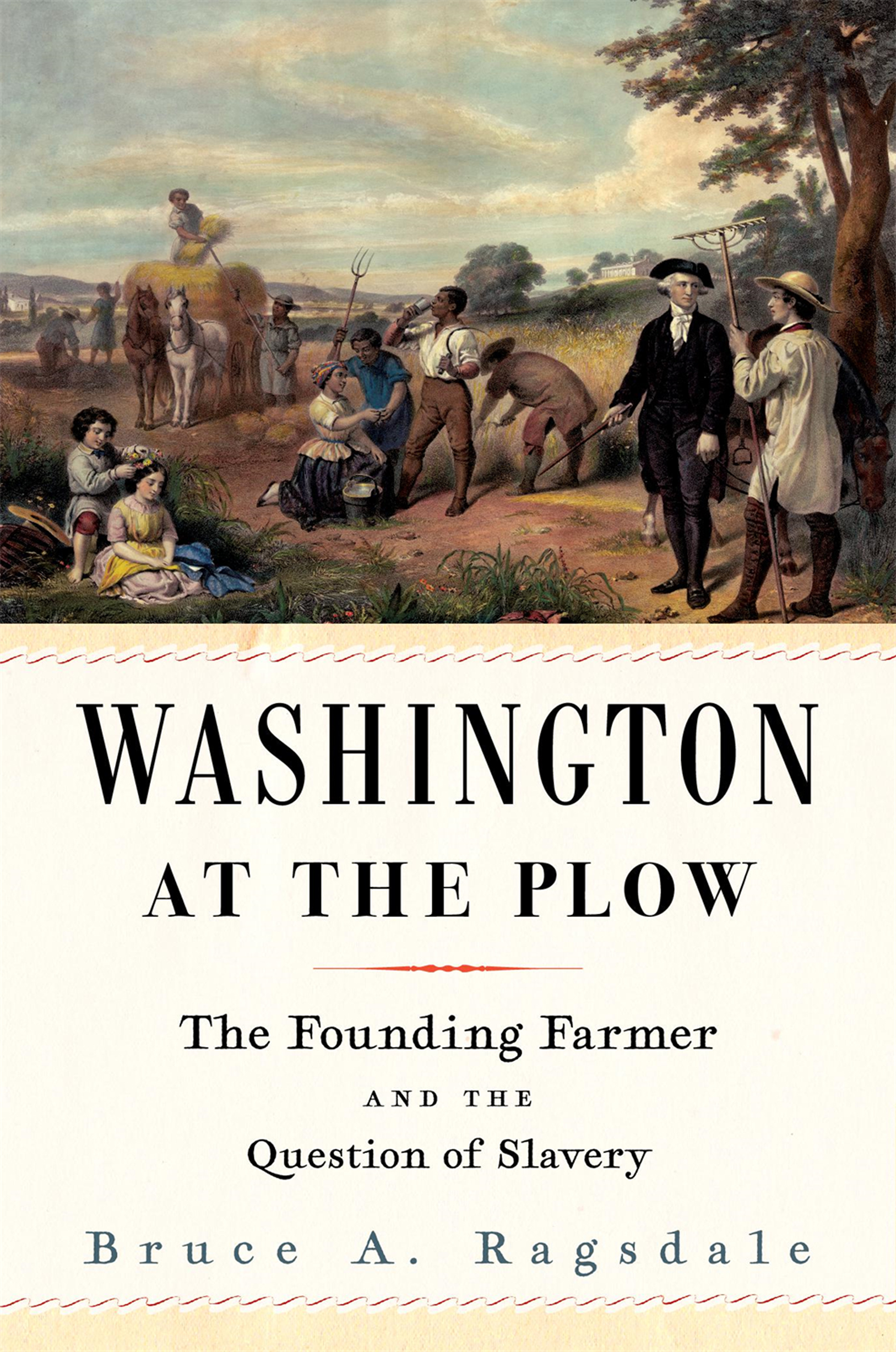

Jacket art: The Life of George Washington: The Farmer, lithograph after painting by Junius Brutus Stearns. Claude Regnier, lithographer. Printed by Imprimerie Lemercier, Paris, c1853. Library of Congress.

978-0-674-24638-6 (cloth)

978-0-674-26990-3 (EPUB)

978-0-674-26989-7 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Ragsdale, Bruce A., author.

Title: Washington at the plow : the founding farmer and the question of slavery / Bruce A. Ragsdale.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021007199

Subjects: LCSH: Washington, George, 17321799. | AgricultureVirginiaExperimentationHistory18th century. | Slave laborVirginiaMount Vernon (Estate) | SlaveryVirginiaMount Vernon (Estate) | SlavesEmancipationVirginiaMount Vernon (Estate) | Mount Vernon (Va. : Estate)History18th century.

Classification: LCC E312.17 .R35 2021 | DDC 306.3 / 6209755dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021007199

For Rick

Contents

n late July 1787, during a brief adjournment of the Federal Convention, George Washington traveled with Gouverneur Morris from Philadelphia to a fishing camp near Valley Forge. In the early morning, while Morris went trout fishing, Washington rode to the nearby site of the former encampment of the Continental Army. He found the remaining works at Valley Forge in ruins, and the grounds of the encampment uncultivated. On his ride back to the fishing camp, he observed some farmers at work and stopped to speak with them. Washington learned about their cultivation of buckwheat, a crop he had recently introduced into his experimental system of farming at Mount Vernon. The farmers told him about the various uses they found for the crop, and Washington recorded their advice on sowing the seed. The chance exchange with the unsuspecting farmers was one opportunity among several Washington had to learn about improved agriculture during the summer he presided over the Federal Convention. He attended a meeting of the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, which had inducted him as an honorary member soon after its founding in 1785. He visited the farm of his friend, Samuel Powel, president of the agricultural society, and together they toured the famous nursery of William Bartram. With other convention delegates, Washington observed a farmers experiments with a soil amendment, which Washington then ordered sent from Philadelphia for application on the fields at his own farms.

Agricultural improvement and the work of nation building were firmly joined in Washingtons mind by the time he attended the convention to draft a new constitution. Soon after his return to Mount Vernon following resignation of his command of the Continental Army, Washington in February 1784 described the prospects for the new nation in the language of farming. We have now a goodly field before us, & I have no wish superior to that of seeing it judiciously cultivated; that every Man, especially those who have laboured to prepare it, may reap a fruitful Harvest. Washington gave life to that metaphor in his ambitious plans for the reorganization of farming at his own estate and in his determination to prove the practicability of an agricultural system that he believed would be the foundation of commercial prosperity and political stability. Agriculture and commerce were inextricably linked in Washingtons vision for the new nation, and he saw in the improvement of agriculture the only source from which we can at present draw any real or permanent advantage; & in my opinion it must be a great (if not the sole) means of our attaining to that degree of respectability & importance which we ought to hold in the world. As he reminded a Maryland planter in the midst of debates on ratification of the Constitution, in the present State of America, our welfare and prosperity depend upon the cultivation of our lands and turning the produce of them to the best advantage. A new agricultural order, based on grain farming and stewardship of the land, would promote settled communities and the shared commercial interests that Washington considered the only durable bond of political unions and the foundation of the rising empire he had envisioned even before the war for independence. The pursuit of agricultural improvement and exchange of scientific knowledge about farming promised to establish peaceful ties between the United States and European nations. Washington equated the promotion of agriculture with the cause of humanity.

The story of Washingtons life as a farmer fundamentally reshapes the familiar biography of the general and president. A commitment to agricultural improvement defined Washingtons pursuit of private opportunities and his expectations for the new nation. The public example of farming at Mount Vernon reflected his ideals of leadership and civic responsibility. Farming framed much about his engagement with the world, near and far, in ways that extended well beyond the marketing of crops. Perhaps most significant, Washington understood slavery primarily through his management of agricultural labor and his recurrent efforts to adapt enslaved labor to new kinds of farming at Mount Vernon. An examination of Washington the farmer also offers a view of his personality and character barely glimpsed through study of his military or political career. Washington considered farming the activity best suited to his disposition, more rewarding than military service or public office, and his agricultural interests revealed a curiosity of mind and boldness of imagination that few discerned in other dimensions of his life. Agriculture was central to Washingtons identity and reputation, and in his life as an innovative farmer, Washington defined a new role for an estate owner in an independent nation.

Washington grew up in an agricultural society dominated by the production of tobacco that was sold on tightly regulated markets in Great Britain. By 1732, the year of his birth, the great tobacco planters who owned enslaved laborers and rich lands along Virginias tidal rivers had gained tremendous wealth and controlled access to both economic opportunity and political authority within the colony. Even as many aspiring planters invested in new enterprises or increased their cultivation of grain, they continued to grow the tobacco that remained the most important means of obtaining British credit and manufactured goods. The tobacco trade with Great Britain also offered wealthy planters access to the center of the empire and the personal services of merchants, who represented Virginians in legal matters and family business. For all of the many advantages of tobacco cultivation, however, the limits of colonial Virginias economic success and the costs of its dependence on British trade would become evident to Washington by the time he assumed direction of his own agricultural estate.

Washingtons family moved when he was three years old from the farm where he was born in Westmoreland County to the later site of Mount Vernon, further up the Potomac. When he was six the family moved again, to a farm in King George County across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg. With each move, Washingtons father, Augustine, worked to increase the value of his investment in the land. Washingtons earliest memories of farming were probably from the lands along the Rappahannock, where his father relied on enslaved laborers to cultivate tobacco and grains. Washingtons mother, Mary Ball Washington, managed the farm during her husbands two trips to England, and again following Augustines death in 1743, when the eleven-year-old Washington inherited the property. Mary Washington controlled enough enslaved laborers to employ a white overseer, and under their management, one of the enslaved workers served as foreman of field hands as they continued to grow tobacco. For much of Washingtons youth, his family faced a precarious economic position but was always attentive to new prospects. Through his parents connections with far wealthier planter families and in the formative time spent with his older brother Lawrence at the expanding Mount Vernon plantation, the young Washington absorbed his first lessons in the successful management of an agricultural estate in Virginia.