The Ever-Changing Past

The Ever-Changing Past

Why All History Is Revisionist History

JAMES M. BANNER, JR.

Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College.

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2021 by James M. Banner, Jr.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Designed by Mary Valencia.

Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020944298

ISBN 978-0-300-23845-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my wife, Phyllis Kramer, the center of my life, and for my beloved children, Olivia P. Banner and Gideon B. Banner

Everything changes, nothing is lost.

Ovid

Contents

Acknowledgments

O ne of the many satisfactions of membership in the confraternity of historians is its collegiality and the willingness of its participants, far-flung and diverse as they may be, to assist others, even those with whom they may disagree, who ply them with questions and requests for assistance of all kinds. Often, especially in our era of electronic communication, one can solicit and receive help from colleagues never met in person. And in a work like this one, which covers so many more centuries and subjects than those that have been my specialty, reliance on others has been as necessary as their assistance has been bountiful and ungrudging.

The first person I salute is the late Roger H. Brown, a superb historian of the early years of the American republic, who was with me when this book germinated in the chambers of Justice Clarence Thomas. Were he still alive, he would doubtlessly smile, and I like to think that he would also approve of what has resulted from that conversation at the Supreme Court. Those of whose assistance, through conversation and correspondence, I have more recently been the fortunate beneficiary in the course of writing this book (some of whom may not even recall our exchanges) have been John E. Bodnar, Angus Burgin, Andrew Burstein, Bruce Cumings, Don H. Doyle, Marc Egnal, John R. Gillis, John F. Haldon, John Earl Haynes, George C. Herring, David A. Hollinger, Nancy G.. And Norman M. Bradburn gave me the benefit of his knowledge for part of the final chapter.

Two people have gone beyond the normal calls of professional col-legiality to read the entire manuscript. One is Sarah Maza, author of a kindred work, Thinking About History, a book that reveals her knowledge of and sympathy for what I have endeavored here, who responded gracefully to my request that she read a draft of the books early manuscript. The astuteness of her observations as well as her suggestions for improvement have been of immense assistance to me. The second is Eric Arnesen, a reviewer for Yale University Press and as engaged, sympathetic, and deep-probing a critic as any historian can hope for. His critical acuteness and attention to detail are rarely encountered in the community of historians, and his influence is to be found on every page of this book. As always, what the reader encounters here also shows the influence of Olivia P. Bannerof editorial pen, as well as of mind, unsurpassed.

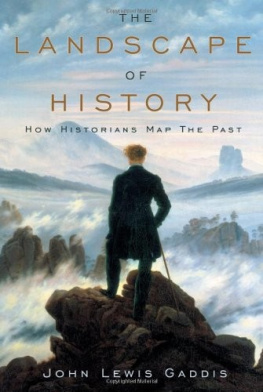

A book is more than its contents; it is an artifact, whose publication and production are the end product of many hands. In thanks for this dimension of the work, I start with my agent Peter W. Bernstein, who shepherded the manuscript to Yale University Press, which, the publisher of two of my previous books, is a kind of home to me and just where this book ought to have ended up. My editor in New Haven, Adina Popescu Berk, has guided the book from submission to publication with emollient skill, sharp intelligence, and unstinting support. Her assistants, Eva Skewes and Ash Lago, have been of immense help in watching over the progress of the books manuscript after its submission. As always, and not without my gently stern insistence to the Press that I would allow the book to go into print only after his editing, Dan Heaton, for this third of my books to pass under his indispensable scrutiny, has once again put his keen eye, command of our common tongue, and affable suggestions on many fronts into play in ways that, though unseen by readers, help give the book whatever value it may possess. To Mary Valencia goes credit for the crisp elegance of the books design, to Jenny Volvovski for its dust jacket, which brilliantly reflects one of my major arguments. Erica Hansons superb, sharp-eyed proofreading saved the book from errors too numerous to count. Margaret Otzel has skillfully and with unbroken good humor carried the book through its entire production process from submission to bound copies.

In expressing my deep appreciation here for the assistance of all of these colleagues, I also happily accept the scholarly convention, so often expressed and long honored, of absolving them of responsibility for what I have written and for any errors that I may have committed.

November 2020

The Ever-Changing Past

Introduction

T his book has its origin in a conversation with Justice Clarence Thomas some years ago in his Supreme Court chambers. At his invitation, a colleague and I were preparing Justice Thomas to meet with a group of teachers who were studying the origins of American constitutional government with us. In the course of a lively conversation, Justice Thomas reported that he was spending the summer reading the history of slavery and the American South. Of course pleased, we asked him whose works he was reading. He named a number of historians, among them John W. Blassingame, John Hope Franklin, and Kenneth M. Stampp, but, he quickly added in so many words, not the revisionists. That statement alerted us, as it would all historians, to the justices readiness, while seeking authoritative knowledge of the subjects he sought to learn about, to dismiss works of historyworks that he had somewhere learned challenged what he thought should constitute and be written about the pastas not worth his attention. It also suggested his misapprehension about the ways historians have approached the past and disputed with each other over two and a half millennia of historical thought, as well as his misunderstanding about the changing nature throughout those centuries of historical inquiry and argumentation. For in fact the works of all the authors Justice Thomas named were revisionist histories, books widely known among professional historians for having deeply altered historical understanding of American slavery, slave society, and the South. From that conversation grew my determination to try to make sense of the realities of what is known as revisionist history. This book is the result.

It ought to be bracing that many people understand enough of the origins, uses, and satisfactions of historical knowledge that they engage with continuing curiosity and pleasure in the play of reasoning that is part of all historical thought and accept with ease the provisionality of historical interpretations that are available to them. Yet it is also troubling to encounter people who dismiss substantiated historical evidence, plausible historical perspectives, and strongly argued, evidence-based interpretations of the past simply because those versions of the past differ from their own, from what they think is proven and safe from challenge, or from what they dream the past ought to have been even if it never was as they imagine it. Consequently, in these pages I attempt to achieve two goals. The first is to strengthen the convictions of aspiring historians in graduate school; their academic teachers, advisers, and mentors; and historians employed outside academic precinctsall of whom may benefit from considering some of the often-overlooked intellectual and theoretical realities of the history of which they are the legateeswhile arming them to explain those realities to others. My second goal is to explain to those in another groupthe legions of general readers who take pleasure in learning about the pastthe grounds on which I invite them to feel more comfortable about the surprises and complexities of the past, about what historical knowledge and arguments consist of, and about how and why professional historians go about creating and evaluating works of history in the way they do. In seeking to do both, I acknowledge the difficulties people everywhere face when asked to accept new understanding of the past and incorporate fresh interpretations into the received ways, to which they are accustomed, of thinking about earlier times. Yet I hope that this book will make clear to them that, as citizens of nations and members of society, they themselves, like millions of others before them, help to shape the way in which the past is conceived and taught. The interpretive changes and contests that I consider are not mere academic realities. Forces and developments outside scholarly circleswhat social scientists call externalitiesexert potent influence on what professional historians conclude about the past at all times. Historians are no more exempt from the realities of their own times than anyone else.

Next page