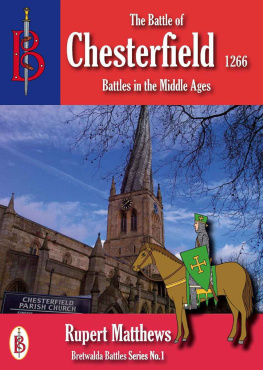

Bretwalda Battles

Medieval Wars

The Battle of Chesterfield 1266

by Rupert Matthews

*****************

Published by Bretwalda Books

Website : Facebook : Twitter : Blog

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First Published 2013

Copyright Bretwalda Books 2013

Oliver Hayes asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this work.

ISBN 978-1-909099-64-7

*****************

Contents

The March to Chesterfield

Leaders at Chesterfield

Men, Weapons and Tactics

The Battle of Chesterfield

Aftermath

************

The Battle of Chesterfield was fought in the later stages of the Barons War, a civil war fought in England between 1264 and 1267. The sheer savagery of what happened in Chesterfield was rooted in that struggle. The major battles of Lewes and Evesham had already been fought, but the war was far from over as the countryside remained in turmoil and nobles were still choosing which side to support.

The town of Chesterfield was then a fairly minor market town, but it occupied a strategic position astride roads leading to York, Derby, North Wales and Lincolnshire. Not only that but it was perched on top of a spur of high ground between two swift rivers and so could be easily defended. Into this walled town came the rebel Robert de Ferrers, Earl of Derby, and his army. Derby was expecting reinforcements from Yorkshire, but they had not yet arrived.

Meanwhile, advancing from the south came Prince Henry of Almain with a larger royalist force. Henry knew where Derby was, but he had no idea where the rebel reinforcements might be, nor how many there were. There were, in fact, no less than four armies manoeuvring around Chesterfield in the middle of May 1266, none of which was entirely certain where the others were nor how strong they were.

The armies would meet in Chesterfield in a battle of great savagery and merciless violence. It was to be one of the most unusual battles of the middle ages as it was waged through the streets of the town, largely after dark and with the men fighting by the light of burning houses. When it was over the streets of Chesterfield ran red with blood and were piled high with the dead and the wounded. The defences of the town had been found wanting and would need replacing.

But although Henry of Almain had won a victory for King Henry III the underlying discontent had not gone away. The royal government would have to give way before peace came to England. And Henry himself had sown the seeds of his own destruction, sparking an act of savage revenge that would come years later and many miles away.

************

The March to Chesterfield

The Barons War that led to the Battle of Chesterfield had erupted in 1264, but its roots reached back over half a century. It proved to be a civil war of enormous importance, far more so than the rather better known Wars of the Roses, for while the war did not lead to a change of ruler or dynasty it did profoundly alter the way in which England was governed, and we still live with those changes today.

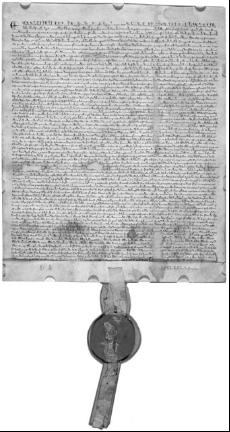

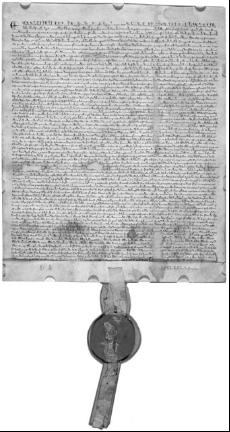

In 1215 King John was forced to confirm the document known as Magna Carta by his rebellious barons. John had been ruling England as a despot, supported by foreign mercenaries. The great charter forced on him by the barons contained many clauses, but the key provision was that even the king had to obey the laws of the land. In dealing with his subjects the king could not arbitrarily imprison, fine or execute at will but only if the person had committed a crime. The weakness of Magna Carta, carefully drafted though it was, was that there was no mechanism to force the king to keep his promises and abide by the charter. However, the civil war that had led to Magna Carta had taught John that he could not do exactly as he wished, and it was a lesson that his son King Henry III had learned as well.

A copy of the Magna Carta, bearing the seal of King John attached to a ribbon underneath. At the time it was agreed and for generations afterwards, Magna Carta was considered to be a touchstone of English liberty for nobles and freemen. Although most of its provisions were fairly arcane measures to stop royal abuse of feudal custom and suzerainty issues that affected only the nobles, whether or not a king was prepared to abide by the great charter or not was thought to be a key indicator of how much he would respect the rights of his citizens. It was the rejection of Magna Carta by King Henry III that laid the foundations for the civil war that was to follow.

However, by the 1250s, Henry was showing signs of following his fathers bad example. He brought in foreign favourites to occupy government posts, hired mercenaries to enforce his will and siphoned off government funds for his own purposes. The most contentious, and expensive, of these came in 1253 when Pope Innocent IV offered to make Henrys second son, Edmund, King of Sicily. Henry was naturally eager to gain such a wealthy and prestigious crown for his son. The catch was that the then King of Sicily, Manfred Hohenstaufen, did not recognise the Popes right to oust him from power and was willing to fight to remain ruler of the island. The resulting war proved to be long and very expensive.

By 1256 the escalating costs of the Sicilian War, added to the underlying concerns that the barons had about King Henry III, led to mutterings against the king. In that year the Welsh Prince Llewellyn II raided into England. Henry raised an army to retaliate, but the expedition was a fiasco plagued by bad organisation, poor supplies and incompetent leadership - all of them Henrys fault.

King Henry III, who ruled England from 1216 to 1272.

The next meeting of the Grand Council, the gathering of all nobles, bishops and major landowners, came on 28 April 1258 at Oxford. Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester and one of the richest men in England, had spent the previous weeks consulting with his fellow grand nobles. They arrived at the council accompanied by armed men and dressed in armour as if for battle. Henry was taken aback by the demonstration of naked power and demanded to know what the nobles wanted.

De Montfort put forward a document that has become known as the Provisions of Oxford and which was, effectively, Englands first constitution. The Provisions stated that the king could enact new laws, raise new taxes or make agreements with other rulers only with the agreement of a Council made up of 24 men, 12 chosen by the Grand Council and 12 chosen by the king. There was to be a new body, the Parliament, composed of representatives elected by the clerics, nobles and knights, which would meet three times a year to supervise and question the Council. And everyone had to abide by the Magna Carta.