S urrey is one of the most charming of English counties, but for those who think they know it, there are some surprises in store. The county is not all suburban gardens, rolling hills and quiet villages. History has been made here, tragedy has struck and fortune has smiled.

Surrey folk today might not notice, but the bridge they drive over may be 700 years old, or might be only the latest in a string of bridges that go back to Roman times. They may, if they go shopping in Epsom, make a purchase in a shop that was once home to Nell Gwyn, the witty mistress of Charles II. Others unknowingly walk on battlefields where brave men fought and died for the causes they believed in.

Those who think Surrey is a peaceful place might be surprised to hear that the army had to be called out to end a riot in Guildford that left houses in flames and a policeman dead. And there have been brutal murders aplenty; some of the killers ended up swinging from a gibbet, but others got away with their brutal crimes.

Not everything in Surrey has been a success either. Take the grandly named Staines, Wokingham & Woking Junction Railway which never got as far as Woking. Then there was the great playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan who moved to Leatherhead to find peace and quiet in which to work, but who got so distracted by the fine fishing that he didnt write a single word the whole time he was there.

But Surrey is not all about the past. There is plenty to be seen today, be it theatres or country walks, wildlife or fine churches. Wherever you are going in Surrey, slip this book into your pocket and prepare to be surprised.

CRIME &

PUNISHMENT

HIGHWAYMEN

The Golden Farmer

Bagshot Heath was once reputedly the most dangerous place in England all because of the activities of a particularly cool, violent and careful highwayman who operated there from about 1647 to 1689. This particular highwayman was known for the guile that he used. He once rode up to a gentleman and told him that there were two disreputable men hanging about the heath and suggested that they travel together for safety. The gentleman agreed, adding that he had 50 guineas on him but that they were sewn into a secret panel of his coat and so would be safe from robbers. After riding for a while, the highwayman remarked conversationally, I believe here is nobody will take the pains of robbing you or me today. Therefore I think I had as good take the trouble upon me of robbing you myself, so pray give me your coat. He produced a pistol and a sword to enforce his demands.

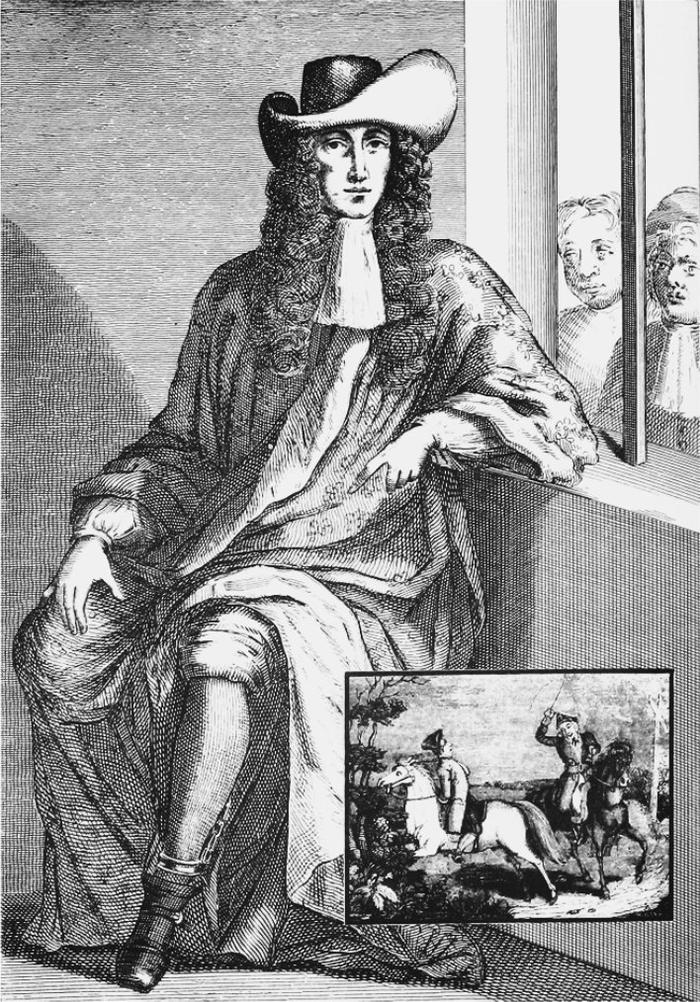

A highwayman confronts the gibbet that stood on Bagshot Heath. This area of virtually uninhabited country was a notorious haunt of robbers and criminals of all kinds.

Another victim came in for rougher treatment. Four ladies in a coach were stopped on Bagshot Heath by the highwayman. Three of them handed over their jewellery but the fourth, an elderly Quaker, said she had nothing of value on her. The highwayman punched her to the ground and shouted, You canting bitch, are you so greedy as to lose your life for the sake of Mammon. Come, come, open your purse quickly or else I shall send you out of the land of the living. His sword then found the ladys neck and prodded, at which point she produced a purse of gold coins and a diamond ring.

A highwayman of the early eighteenth century. The years 1690 to 1730 were the heyday of highwaymen as the authorities had not yet instituted an effective force to police the open roads.

One of the puzzles about this particular highwayman was that nobody who was robbed either recognised him or saw him again. It was almost as if he robbed, then vanished. The mans luck ran out in November 1689 when a former victim recognised him drinking in a tavern in Fleet Street, London, and called the watch. The notorious highwayman of Bagshot Heath turned out to be an apparently law-abiding farmer in Gloucestershire named William Davis. This Davis lived a blameless life on his farm, but went on frequent visits to London returning with large amounts of money that he said he had won at the gaming tables. So much wealth did Davis bring home that his neighbours nicknamed him the Golden Farmer. He was hanged before the year was out.

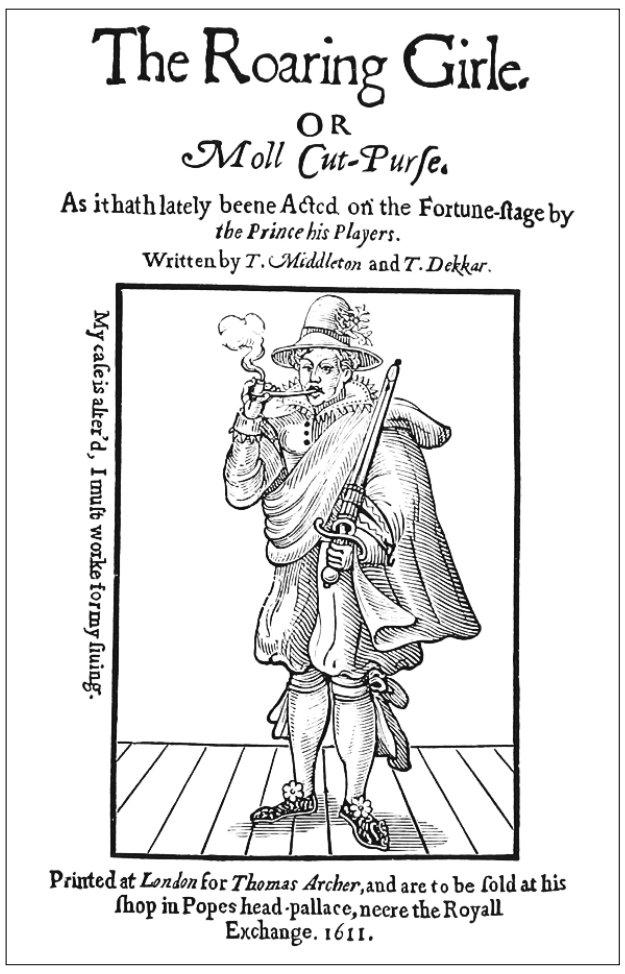

The Roaring Girl

One of the few highwaywomen on record also robbed on the heaths of north Surrey. Mary Frith (more famously known as Moll Cutpurse) spent most of her criminal career as a fence, receiving and selling-on stolen goods, but in the conditions of chaos of the English Civil War she decided to try her hand at highway robbery. In 1651 she and her henchmen stopped a coach that was carrying no less a person than Sir Thomas Fairfax, commander-in-chief of the Parliamentary armed forces.

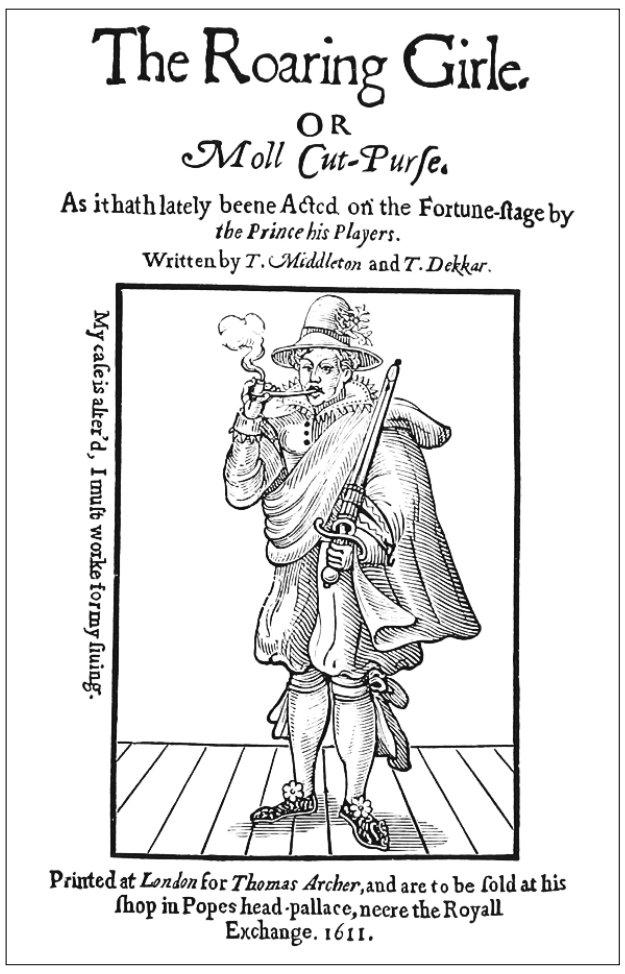

The frontispiece for a version of the popular play The Roaring Girle, which was based on the colourful criminal career of Surrey girl Mary Frith.

She got away with a hefty 250, but Fairfax was furious and had the authority to organise a massive operation against highwaymen near London. Frith was caught, but bought her freedom by paying a fine of 2,000 then a colossal sum of cash. She then wisely turned honest to evade the notice of the authorities. She died in 1659 and left 20 in her will to fund a party for named individuals should England ever become a kingdom again, which it did the following year. A play about her life, called The Roaring Girle, was written with her assistance.

The Butcher of Bagshot

James Whitney was a butchers son from Hertfordshire who tired of the hard work involved in his fathers trade at a young age. He then ran off to London to lead a life of petty crime, heavy drinking and wanton womanising.

In 1683, at the age of twenty-three, Whitney decided that he needed to improve himself. He bought himself an elegant suit of fine clothes together with a rapier and a pistol, then stole the best horse he could lay his hands on and became a highwayman. Because many of the first highwaymen had been gentlemen fallen on hard times through supporting the king in the Civil War, the criminal classes looked up to highwaymen as being a social cut above mere pickpockets and burglars. Whitney ostentatiously lived up to the ideal by wearing flashy jewellery, exquisitely tailored suits and behaving with impeccable politeness at all times even when holding a gun to a mans head he remembered to say please and thank you.

By 1690 Whitney was leading a gang of some fifty men. Not all of them rode with him, some lolled about in inns looking for rich victims, others fenced stolen goods and at least one worked for the Surrey magistrates to keep an eye on what they were doing. It was this spy who reported that Mr William Hull had sworn that he would one day watch Whitney ride his horse backwards a reference to the fact that men to be hanged were taken to the gallows tied sitting backwards on a horse. Whitney led his gang to waylay Hull a week later. The unfortunate man was robbed, then tied backwards on his saddle and let loose across Bagshot Heath while the highwaymen jeered at him.