To Glastonbury Coromandel

CONTENTS

The illustrations are taken from the following publications:

A History of Scotland for Schools by P. Hume Brown (1907)

An Account of the Bell Rock Light-House by Robert Stevenson (1824)

Boys Own Annual (1905)

Chatterbox (1914)

The History of Scotland by James Mackenzie (1894)

The Humorist (1923)

Larousse Petit Encyclopdie Illustre (1906)

London Opinion (1920)

The National Burns (1879)

Punch (18821919)

Sir Walter Scott by W.S. Crockett & J. L. Caw (1903)

As ever, many thanks to Sgolne Dupuy.

Oh, yell take the high road,

and Ill take the low road,

And Ill be in Scotland afore ye.

You probably know these lines theyre from the famous traditional Scottish song The Bonnie Banks o Loch Lomond. So well known is the song that it gave its name to Take the High Road , a Scottish daytime soap opera that ran from 1980 to 2003. The series was filmed on Loch Lomond the very place celebrated in the songs lyrics: For me and my true love will never meet again, On the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond.

Nobody really knows how old the song is, nor what the lyrics mean. The song has usually been interpreted as a lament related to one of the Jacobite rebellions. Other people think it may have something to do with a criminal due to hang in England, or perhaps a tale of the supernatural is the low road the land of the dead? All these interpretations, however, may be wide of the mark. Quite simply, this beautiful, emotional and universally known ballad is a complete mystery.

That, to me, sums up Scotland. A country of worldwide fame, with a distinctive culture and a strong heart, it is nevertheless something of an enigma.

Some parts of Scotlands story are universally celebrated or championed, while other aspects have been neglected, even obscured. It is widely perceived as a romantic land of castles and mountains, and yet the vast majority of its people live in modern cities. A simplistic view of continual tension with its southern neighbour clouds a much more complex history of shifting allegiances and enmities within Scotland itself, often reflected in the fundamental geographical and cultural difference between the Highlands and the Lowlands. Even the elements that commonly define Scottish identity the kilt, the bagpipes, tartan have changed their meaning so much that a visitor from, say, just two centuries ago, would struggle to understand how it is they mean so much to modern Scots.

And so here you will find many surprising, hidden and quirky aspects of Scotland, from history to hovercrafts, from whisky to wine, and from extreme food (haggis, anyone?) to some extremely odd sports.

Welcome to a Scotland that is strange, marvellous, madcap, dark, glorious, peculiar, and spectacular often all at the same time.

Take the high road.

PREHISTORIC DAYS

The oldest calendar in the world was constructed by nomadic hunter-gatherers in Aberdeenshire 10,000 years ago. Twelve wooden posts set up at Warren Field near Crathes Castle mimicked the phases of the moon and recorded the lunar months, allowing the seasons to be followed. The Mesolithic device is almost 5,000 years older than the first recognised formal calendars known from ancient Mesopotamia.

Aberdeenshire contains approximately 10 per cent of all the 900 stone circles in Britain.

The Ring of Brodgar on the mainland of Orkney is the third largest stone circle in the world. The numerous prehistoric monuments in the area are collectively listed as a World Heritage Site known as the Heart of Neolithic Orkney.

Callanish on Lewis in the Western Isles is one of the most elaborate prehistoric sites in Britain. Featuring a stone circle with a cross-shaped series of stone rows, the complex is focused on the 18.6-year cycle of the moon across the heavens.

Lewis also has the tallest standing stone in Scotland. The Clach an Trushal monolith is over 19ft in height.

One of the most spectacular prehistoric sites is at Machrie Moor on Arran, where seven stone circles stand in close proximity to each other.

A prehistoric monument unique to Scotland is the broch, a cylindrical stone defensive/residential proto-castle that looks like a scaled-down power station cooling tower. Double-skinned, the walls were honeycombed with internal stairs and chambers. Brochs survive to a reasonable height in Lochalsh, Skye and the Western Isles. The best is at Mousa in Shetland.

The mysterious stone monuments of the Neolithic and Bronze Ages were still regarded with awe into the modern age. Many burial mounds were thought to be the home of fairies or spirits. Women visited various stones thought to promote conception and/or a safe childbirth at Darvel (East Ayrshire), Pitreavie (Fife), Dingwall (Ross & Cromarty, Highland) and Clach-na-bhan (Aberdeenshire). Such visits continued until at least the mid-nineteenth century.

WHAT DID THE ROMANS EVER DO FOR US?

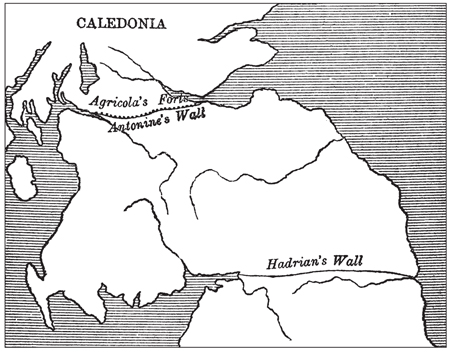

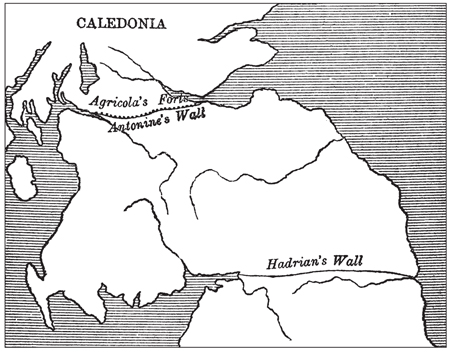

Hadrians Wall did not mark the limit of the Roman Empire. There are two (far less well-known) Roman frontiers further up Scotland: the Antonine Wall ( AD 142144), parts of which can still be seen on the narrow neck of land between Glasgow and the River Forth; and the Gask Ridge, a true Wild West frontier of forts and watchtowers running from Camelon in Falkirk District north-east through Stirling District and Perth & Kinross to Stracathro in Angus.

Having been built between AD 70 and AD 80, forty-two years before the start of building works on Hadrians Wall, the Gask Ridge is the earliest fortified land frontier in the Roman Empire. It effectively separated the fertile plains and important harbours of the Lowlands from the less valuable (and more difficult to control) Highlands perhaps the first political recognition of the fact that Scotland has two distinct geographies. The tensions and differences between the Highlands and the Lowlands have remained a factor of Scottish life ever since.

In the first century AD the Roman army briefly penetrated even further north, reaching Aberdeenshire, Moray and as far as present-day Inverness.

The idea that everyone in Iron Age Scotland painted themselves with blue woad, lived a wild but free life and hated the Romans is a myth that has its roots in misguided nineteenth-century romantic patriotism. Some Lowland Caledonian tribes were more than happy to take bribes of silver and luxury Mediterranean goods (like wine) in exchange for not disturbing the Pax Romana . And a number of Lowland farmers did very nicely selling grain and other agricultural products to the hungry Roman troops. Even Hadrians Wall wasnt the military exclusion barrier it has been portrayed as many of its gates were open most of the time to allow the passage of goods and animals for market goods and animals, that is, sold by the local tribes.

Roman influence in Scotland ebbed and flowed, depending largely on what was happening elsewhere in the Empire. After AD 211, with a few exceptions, the Romans largely withdrew to Hadrians Wall.

Next page