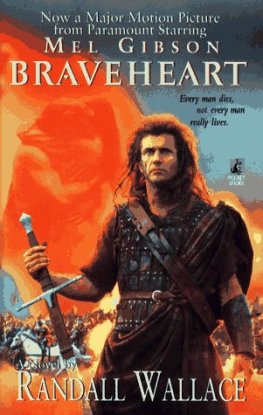

BRAVEHEART

A novel by

Randall Wallace

To Scottish friends I lift a glass

To you, whove kept alive

The memory of heroes past

Across dark moors of time

To you who know this simple truth

And show it near and far

It is the tales we tell ourselves

That make us who we are

So let us drink to Scotland fair

Its sorrow and its solace

And lift our glasses in the air

To you and William Wallace

And to the Clan that bears his name

My sisters and my brothers

Id rather be a man in your eyes

Than a king in any others

Randall Wallace

William and Murron rode along the ridge to a grove, from which they could see a breathtaking loch. There he turned to her in the moonlight

I have fought. And I have hated. I know it is in me to hate and to kill. But Ive learned something else away from my home. And that is that we must always have a home, somewhere inside us. I dont known how to explain this to you, Murron; I wish I could. When I lost my father and brother, it hurt my heart so much. I wished I had them back! I wished the pain would go away. I thought I might die of grief alone! I wanted to bring that grief to the people who had brought it to me.

Williams words were coming fast now. Slow to get started, they had become impossible to stop. But later I came to realize something. My father and his father had not fought and died so I could become filled with hate. They fought for me to be free to love. They fought because they loved! They loved me. They wanted me to have a free life. A family. Respect from others, for others. Respect for myself. I had to stop hating and start loving.

He squeezed her hands. He reached with trembling fingers and combed her windblown hair away from her face, so he could see it fully. But that was easy. I thought of you.

The journey of Braveheart has taught me about clanship, that bond of loyalty and shared devotion that unites across time and miles. I have seen in new ways how those who have loved me and prayed for me have become a part of all I do.

Such a bond goes beyond thanks; but there are some who, because of the miles they walked on the path that led to his book, must not go unmentioned here. They are:

Evelyn and Thurman Wallace, my mother and father, for the legacy of their example that all freedom begins with freedom of the sprit, and that it has a price, pain the currency of love. And my sister, Jane Wallace Sublett, who, by loving me so consistently through victory of defeat, has helped me accept both, and fear neither.

James W. Connor, who, even before I did, believed I would write novels someday.

Dr. Thomas Langford of Duke University, who taught me that deeds were the finest sermons, and who opened my life to the possibility that every prayer was a story, and every story a prayer.

Judy Thomas, who helped me believe that all writhing should sing the silent music of the soul.

James J. Cullen, whose screenplay about heroism and honor was the first-and still is one of the finest-I ever read, and whose poetic glories inspired me to attempt such a work of my own.

Rebecca Pollack Parker, who when the inspiration for Braveheart was but a spark, embraced it in the lantern of her sprit and nurtured it to flame.

Lisa Drew, editor of this book, whose relentless faith in my novels has brought me back to writing them.

And let me not forget Blind Harry, roving minstrel of Scotland, who kept alive the tales of William Wallace.

And always and forever, my wife, Christine, and our sons, Andrew, and Cullen. Among all the other gratitudes for my family, there is this: to write truly of love and women of strength, one must know them- and I know Christine. And the sprits of our sons are a constant revelation of Gods sweetest strategy: he gives us a gift so great that we would give our lives in return.

This book is for you all.

I will tell you of William Wallace.

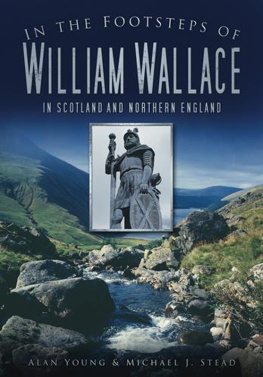

I first encountered his story when my wife and I came upon the statue of him that, along with one of King Robert the Bruce, guards the entrance to Edinburgh Castle in Scotland. I am an American; I had grown p in the American South within a family I know to be Scotch-Irish, and although I had always been interested in history, I never through much about our roots extending beyond America. We were dirt farmers from Tennessee. What I am trying to say is that I never thought of our having famous relatives.

Songs of William Wallace have been sung for hundreds for years, and not just by Scotlands poets along- even Winston Churchill wrote, with keen admiration, about Wallaces courage and sprit. But to me, an American, his story seemed lost, a great treasure of the past, utterly precocious of our time, lying neglected and forgotten. His story began to speak to me, to haunt me; it entered my live as divine gifts do, quietly, overwhelmingly irreversibly.

Historians agree on only a few facts about Wallaces life, and yet they cannot dispute that his life was epic. There were times when I tried myself to be a fair historian, but life is not all about balance, its about passion, and this story raised my passions. I had to see through the eyes of a poet.

No one knows what William Wallace whispered into the ear of the woman he loved most. No one else heard the words he spoke to God when he prayed. And the words he shouted to his army, when the men who fought behind him were desperately outnumbered were recorded only in their hearts and can be read there.

In my heart, this is exactly how it happened.

THE BOY

THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS ARE A LAND OF EPIC BEAUTY: cobalt mountains beneath a glowering purple sky fringed with pink, as if the clouds are a lid too small for the earth; a cascading landscape of boulders shrouded in deep green grass; and the blue lochs, reflecting the sky. In summer, the sun lingers for hours in its rising and setting; in winter, day is a brief union of dawn and twilight. In all seasons the night is a serenade of stars, singing white in the silence of an endless black sky.

Elderslie lies between Glasgow and Edinburgh, at the gateway into the Highlands. It was in the shire or Elderslie, in or about the year 1276, that a contingent of mounted Scottish noblemen converged on a farm nestled in an isolated Scottish valley. The noblemen wore sparkling chestplates and woolens colored with the richest dyes of the day; even their horses draped in luxurious cloth. But they had left their armed escorts far behind, for this was a meeting of truce, and the terms were that each nobleman could be accompanied by a single page boy. The nobles had agreed, for each know that their country needed peace, and to have peace, Scotlands crown must have a head to wear it, and they had to have a meeting to establish just whose head that should be.

Their old king had died without an heir. The rightful succession belonged to an infant girl, called the Maid of Norway, and the nobles of Scotland sent for their new queen. The Vikings, cousins to the Scots, agreed to bring her down on one of their ships.

On the English throne in London sat King Edward I, known as Edward the Longshanks because of his lengthy legs. He disputed the ascension of the baby to the throne and claimed the right to chose Scotlands new monarch lay with him and him alone. Longshanks was a Plantagenet, a line of rulers renowned for their ruthlessness and accused by their enemies of worshiping pagan deities that delighted in cruelty. And so when the baby died on her journey south, there were those who said she had been smothered and Longshanks was to blame.