Bretwalda Battles

The Wars of the Roses

The Battle of Nibley Green 1469

by Leonard James

*****************

Published by Bretwalda Books

Website : Facebook : Twitter : Blog

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First Published 2014

Copyright Bretwalda Books 2014

Leonard James asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this work.

ISBN 978-1-909698-92-5

*****************

Contents

****

On a spring morning in 1470 the peace of Gloucestershire was shattered by the sounds of battle. The Wars of the Roses had come to this peaceful corner of southwestern England in spectacular and bloody fashion.

But the battle fought at Nibley Green had very little to do with the dispute between the House of York and the House of Lancaster. The fate of the throne was not at issue at Nibley Green, nor were the underlying social tensions between the ancient landed aristocracy and newly rich mercantile classes that lurked behind the dynastic dispute. No, the fight at Nibley Green might have been dressed up as a principled stand over support for the rightful king (whoever he was) but in reality it was a brutal affair fought to settle a local dispute between local aristocrats and local magnates.

Nibley Green has, perhaps rightly, been identified as the last of the private battles that had been such a feature of medieval England. As such it reveals much about late medieval society, and the ways in which men went about fighting battles in that bloody era.

****

The Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses of which Nibley Green formed a part were fought with a curious mix of merciless savagery and almost considerate care that has not been seen in wars in Britain either before or since. The struggle tore England apart between 1455 and 1497.

The peculiar character of the wars can be traced back to the reasons they were fought and the characters of those involved. They remained at heart a dynastic battle fought for political power between the two main branches of the Plantagenet dynasty that had ruled England since 1154. It was ironic that the great struggle between the two would result in an entirely different dynasty taking the crown in the shape of the Tudors.

The foundations for the struggle were laid in 1399 when Richard II was overthrown by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, who became Henry IV. Richard IIhad proved to be a weak king and a petulant and spiteful man. He raised taxes to pay for his luxurious lifestyle, then executed those who objected. The final straw came when John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster died. Gaunts eldest son, Henry Bolingbroke, had already been sent into exile by Richard on trumped up charges. Now Richard announced that the entire, vast Lancaster estates were confiscated by the crown.

Bolingbroke was furious, but he was also very popular among both the nobles and commons of England. On 4 July Bolingbroke landed in Yorkshire declaring that he had come to reclaim his rightful inheritance and to reform the evil government of England. Men flocked to his banner, even royal castles throwing their gates open, and nobody supported Richard at all. What made Bolingbrokes arrival dangerous was that he, like Richard, was a grandson of King Edward III. Before long Richard was in prison and Bolingbroke was being hailed as King Henry IV. Richard died conveniently soon after and since he had no children, Henry IVwas secure on the throne.

Almost unnoticed at the time was a great grandson of Edward III. This was Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, who was just 8 years old. By the rules of inheritance at the time, it was Edmund who should have become king when Richard II died, but being so young, Edmund was ignored by everyone involved and, indeed, was seen to support the new King Henry IV.

Henry IVproved to be an effective and popular monarch, as did his son, Henry V. But trouble flared when Henry Vs son became king as Henry VI. The new king proved to be a weak man who was easily influenced by those around him. He gained a reputation for piety and gentleness, but his government grew progressively worse. Henrys queen, Margaret of Anjou, was a grasping and scheming lady who surrounded herself with clever but amoral men intent on milking the state treasury for their own benefit.

Those opposed to Margaret and her henchmen gathered around Richard, Duke of York, who governed the extensive English lands in France with honesty, fairness and efficiency. Contrasted with the mess at home in England, Yorks government was a shining example. Margaret was furious with York for his success and persuaded King Henry to withdraw him from France. York was too dangerous to keep in England so he was packed off to Ireland with a ten year appointment to administer the royal lands there.

Then in 1453 King Henry VI fell into a stupor. At the time it was said that he had gone mad, but it would now seem that he suffered some form of major mental breakdown that left him unable to respond or react to what went on around him. Noblemen opposed to Margaret of Anjou clamoured for York to be brought back from Ireland and made Regent of the Kingdom during the Kings madness. Among these emerging Yorkists was the Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, perhaps the richest man in England after the king and a dashingly handsome young man with an emerging reputation as a talented military commander. the Duke of York came back to England from Ireland, took the title of Lord Protector and began ruling England. His regime soon proved to be every bit as efficient and honest as had his rule in France.

Then in 1455 Henry recovered his senses. The Council of Regency was disbanded and Margaret and Somerset put back into office. It was at this point that a famous incident is supposed to have taken place, though contemporary evidence for it is lacking. A large group of nobles was taking the air in the gardens of the Temple Church in the city of London during a court meeting when York entered through one gate and Somerset a few seconds later by way of another. York then picked a white rose from a bush in the garden, the white rose being a heraldic badge associated with his family. Somerset promptly picked a red rose from a different bush. Warwick then picked a white rose, followed by nobles supporting York, while those backing Somerset hurried to pick red roses and those unwilling to commit themselves in so obviously a dangerous dispute rushed to get out of the garden.

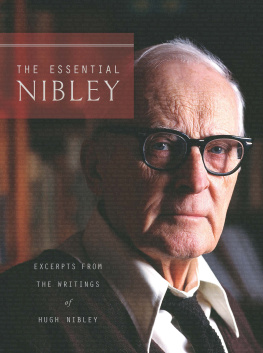

King Henry VI reigned from 1422 when he inherited the throne at the age of just nine months. He grew up to be a weak, indecisive man who suffered episodes of mental illness. His inability to keep a firm grip on government led to the Wars of the Roses.

What made York all the more dangerous to Margaret, Somerset and their supporters was the fact that he was the grandson of Edmund Mortimer, the boy who had been passed over when Henry IV became king. In strict legal terms, York should have been king, not Henry. Neither York nor his supporters pushed this claim, but everyone knew about it and it lurked in the background of all these events.