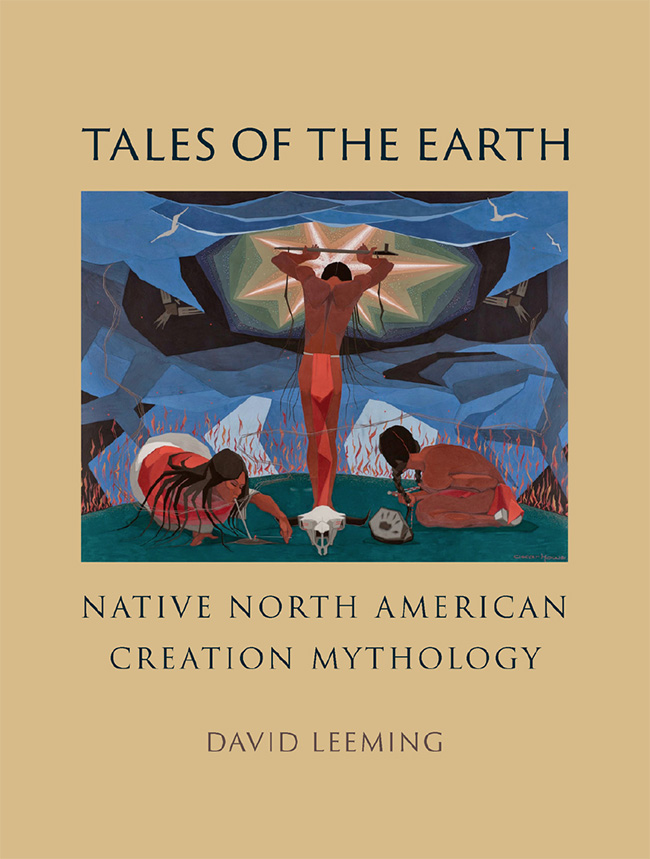

TALES OF THE EARTH

NATIVE NORTH AMERICAN

CREATION MYTHOLOGY

DAVID LEEMING

REAKTION BOOKS

In memory of Little Antelope and Jake Page

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright David Leeming 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789145007

CONTENTS

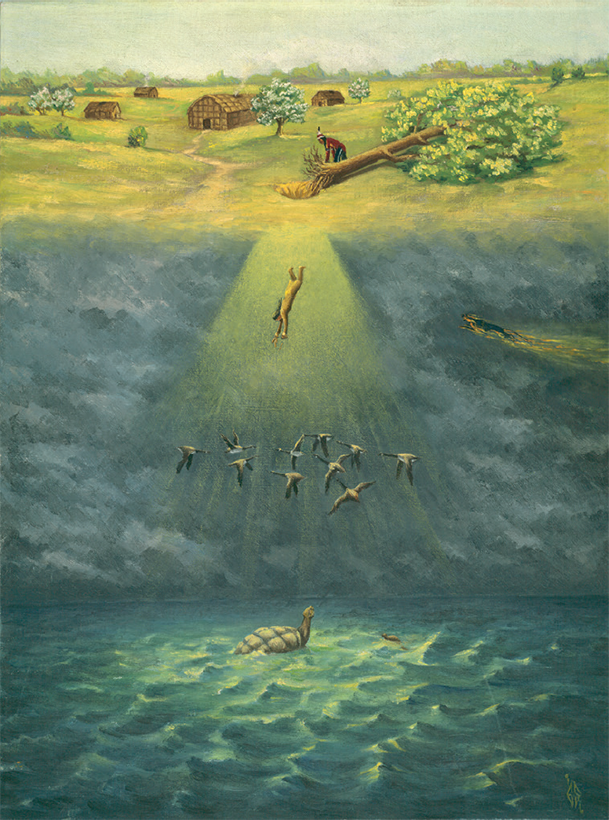

Ernest Smith, Sky Woman, 1936, oil on canvas. The painting depicts a moment in the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) narrative of the worlds creation in which a woman falls from the Sky World toward the dark watery world below.

Preface

T he myths of a people are their cultural dreams. In this book my purpose as a non-Native American is to study these dreams with a goal of better understanding the people who lived in what is now the United States before my ancestors arrival.

To treat the mythology of the native North Americans as a viable category is, of course, intellectually dangerous. The more than five hundred tribes in North America all have their own mythological traditions. These tribes are part of early migrations to the Western hemisphere that included the ancestors of the indigenous peoples of Meso-America and South America. An obvious universal presence in Native North American mythology, however, is the creation myth. Scholars have long noted the existence of several basic creation myth types in world mythology. These include types that are amply represented in Native North American mythology: the ex nihilo (from nothing) creation, the from chaos creation, the world parent creation, the earth diver creation and the emergence creation. What stands out in Native North American creation myths of all types is the animistic concept of the spirit-infused sacredness of the land and everything in it.

I have begun with an introduction that provides a context for the mythology. Where did the first Americans come from and how and why did they come? How were the first Americans seen by the is the hero. In Native American mythology this hero is sometimes specifically a culture hero, or his quest is to slay the monsters who threaten creation. A conclusion addresses the position of Native American mythology in the values and priorities of the United States. What is the place of Native American mythology in historical and modern American culture? How does Native American earth-based polytheistic mythology coexist or conflict with European American monotheistic and nationalistic mythology?

Native American mythology has, until relatively recently, been passed down orally rather than in written form. Versions of myths vary not only from tribe to tribe but from village to village, clan to clan, family to family, storyteller to storyteller, and medicine person to medicine person. There is no Native American equivalent of the Bible, the Quran or the Vedas. Native American mythology is an oral mythology. Myths were written down by non-Native Americans such as Henry Schoolcraft, George Bird Grinnell, Jeremiah Curtin, Lewis Spence and Hartley Burr Alexander, and indigenous people such as Jesse Cornplanter, beginning only in the nineteenth century, and by later scholars and collectors, including Richard Erdoes, Alfonso Ortiz, John Bierhorst and N. Scott Momaday, to mention only a few. The retellings in this book are based on combinations of these and many other sources, including conversations with Native Americans.

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, The First Thanksgiving, 1621, c. 1912, oil on canvas.

INTRODUCTION

Who Are the Native Americans?

E very American schoolchild knows that Christopher Columbus discovered America in 1492 (or maybe it was the Viking Leif Erikson in the eleventh century). The same children are told that in 1620 English Puritans, referred to as the Pilgrims, came to America on the Mayflower, and that in 1621 they celebrated a thanksgiving harvest feast with people (including a native named Squanto) who already lived there. They are told, too, that Columbus, when he had arrived in what we still call the West Indies islands, believed he had found his way to India, and so he named the inhabitants Indians. This is a name that has ever since been attached to the inhabitants of the Americas who were there when Europeans arrived. Children also learn that other English people not Puritans had arrived in America even earlier than the Pilgrims and had settled Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 under the partial leadership of Captain John Smith. Smith was captured by Native Americans who already lived in Virginia, and it is said that he was saved from execution by the brave intervention of an Indian princess, Pocahontas.

Elements of these stories are apocryphal. But the essential truth about all of them is that when Europeans whether Leif Erikson, Columbus, John Smith, the Pilgrims or earlier explorers in the early seventeenth century arrived, the Americas were already populated by well-established nations of people. These people included those discovered by the Spanish in the southern and western regions of North America, discoveries that preceded those of the English. Florida was occupied by the Spanish under Pedro Menndez de Avils in 1565 following initial raids by Hernando de Soto. What is now New Mexico was explored by Francisco Vsquez de Coronado before Juan de Oate created settlements there in 1598. The most obviously advanced of the Native American nations prior to European invasion existed further south in Meso-America (modern-day Mexico and Central America) and South America. When the Spanish conquistador Hernando Corts arrived in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519 he found a city larger and much better appointed than any European city. And much older cities had existed in Meso-America and South America before Tenochtitlan.

Opposite: Pieter Balthazar Bouttats, after Theodor de Bry, Admiral Christopher Columbus Discovers the Island of Hispaniola, engraving from Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Historia general de las Indias Ocidentales (1728).

Unknown artist, after Simon van de Passe, Pocahontas [in Europe], after 1616, oil on canvas.