First published 2009 by M.E. Sharpe

Published 2015 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2009, Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use of operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lifelines in world history / Mounir A. Farah, general editor.

v. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: v. i. The ancient world v. 2. The medieval world v. 3. The early modern world

v. 4. The modern world.

ISBN 978-0-7656-8125-6 (hbk. : alk. paper)

1. Biography. 2. World history. 3. CivilizationHistory. I. Farah, Mounir.

CT104.L44 2008

909dc22

2008016288

ISBN 13: 9780765681256 (hbk)

Much has been written about the role of the individual in history. To what extent does one person influence or determine the course of events in a country, a region, or the world? What characteristics do influential leaders have that enable them to affect vital issues and shape the affairs of nations? Historians and philosophers have long debated these questions but have never reached a consensus.

Many assert that political, economic, social, and technological factors in a society help determine what happens at any given time. Others believe that the decisions of a powerful leader or the inventions of a great scientist are the real keys in determining the course of a nation, in other words, that people shape history.

To explore the interplay between individuals and political, economic, and social circumstances, Lifelines in World History presents biographical sketches of some of the most important and fascinating people of recorded time. Drawing from the ancient, medieval, early modern, and modern worlds, editors have chosen to study influential or powerful or inspiring political and military leaders, religious founders, artists, philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians, people whose accomplishments and deedsboth good and badhave shaped the world.

Lifelines in World History: The Ancient World

For more than two thousand years of ancient history, great leaders in political, military, and intellectual arenas have played dramatic roles in the events that made lasting differences in their societies. Lifelines in World History: The Ancient World examines their lives and influences. During the fourth century B.C.E ., for example, Alexander the Greats leadership and military ingenuity were decisive in Greek and Macedonian victories and the consequent spread of Hellenic culture and civilization. The ideas developed by the likes of Confucius, Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle changed the way people perceived themselves and the world around them.

It can also be argued, however, that without the warfare between ancient Greek city-states, Alexander the Great would never have emerged as the strong leader that he was. Without the devastation of the Peloponnesian War, Plato would not have advocated an elitist republican form of government administered by intellectuals. It was the suffering that Gautama observed beyond the walls of his fathers palace that moved him to develop a new religious philosophy. The ancient Egyptian pharaohs are credited with the building of awe-inspiring pyramids. Yet the pharaohs were able to achieve these monumental feats because they enslaved thousands of people. Was it the military genius of Attila that expanded the domain of the Huns? Or, was it the weakness and the decline of Rome that made Attilas successes possible?

Lifelines in World History presents highlights of the lives of these and other important figures. We ask readers to contemplate the role of these personalities and reflect especially on the circumstances of the time that made their efforts noteworthy. For each subject, we believe readers will agree that there is not only some feat of lasting importance but also a powerful connection to today.

Mounir A. Farah, Ph.D.

General Editor

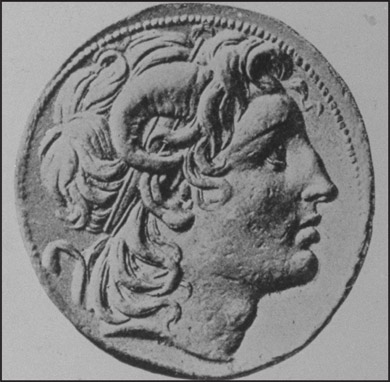

(356323 B.C.E .)

King of Macedon who conquered Persia and other lands and established the largest empire in the ancient world. Alexander not only brought large portions of Southwest Asia, India, and Egypt under his control but also promoted the spread of Hellenic Greek culture throughout his conquered territories. Thanks to Alexander, Greek philosophy, art, and science took deep root throughout what is now Turkey and much of the Middle East. The synthesis of the Hellenic culture and the ancient cultures of the conquered Middle East became known as the Hellenistic culture. Hellenistic civilization influenced the eastern Mediterranean region for centuries after Alexander.

Early Life

Alexander was born in 356 B.C.E ., the son of King Philip II of Macedon (also known as Macedonia) and his wife, Olympias. Philip was a superior military leader, and under his rule Macedon (in what is now northwestern Greece) eventually emerged as the most powerful of the Greek city-states . At the time of Alexanders birth, however, Macedon was competing with the neighboring city-states of Illyria and Thessaly for dominance over northern Greece.

Alexanders mother, Olympias, was the daughter of King Neptolemus of Epirus, a small city-state in central Greece. Like many kings of the era , Neptolemus claimed to be descended from divine parentsin this case, the Greek god Achilles. Many rulers spread such stories in order to support their claims to the throne. Olympias apparently encouraged young Alexander to believe in these tales of his divine ancestry. Some historians suggest that Alexander believed himself to be a god, and that this fueled both his desire to rule a great empire and his fearlessness in battle.