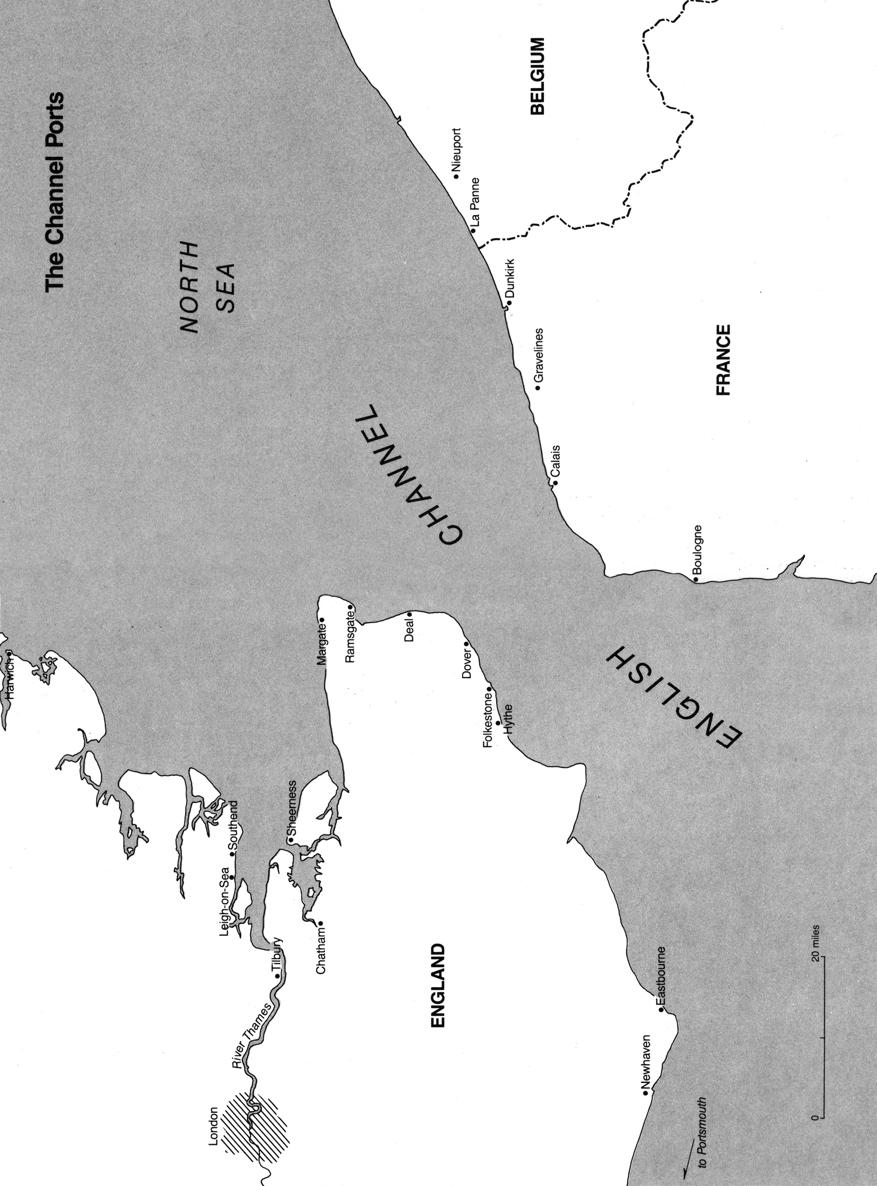

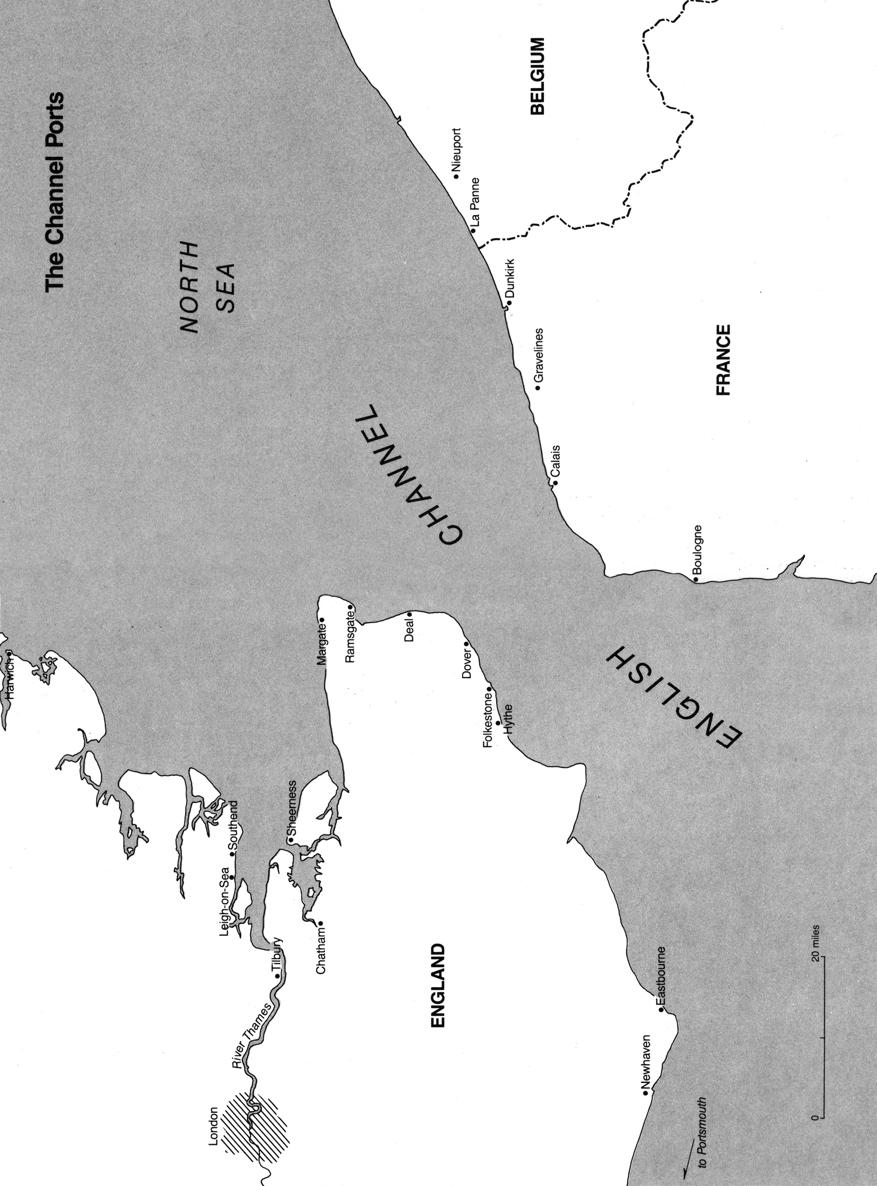

List of Maps

May 10 - 20, The German Drive to the Sea

May 24, The Allied Pocket

May 24 - 30, The Allied Escape Corridor

May 27, The Perimeter

The Three Routes Across the Channel

Dunkirk Harbour

Foreword

THERE SEEMED TO BE NO ESCAPE. On May 24, 1940, some 400,000 Allied troops lay pinned against the coast of Flanders near the French port of Dunkirk. Hitlers advancing tanks were only ten miles away. There was virtually nothing in between.

Yet the trapped army was saved. By June 4just eleven days laterover 338,000 men had been evacuated safely to England in one of the great rescues of all time. It was a crucial turning point in World War II.

So long as the English tongue survives, proclaimed the New York Times, the word Dunkerque will be spoken with reverence. Hyperbole, perhaps, but certainly the wordthe eventhas lived on. To the British, Dunkirk symbolizes a generosity of spirit, a willingness to sacrifice for the common good. To Americans, it has come to mean Mrs. Miniver, little ships, The Snow Goose, escape by sea. To the French, it suggests bitter defeat; to the Germans, opportunity forever lost.

Theres an element of truth in all these images, but they fail to go to the heart of the matter. It is customary to look on Dunkirk as a series of days. Actually, it should be regarded as a series of crises. Each crisis was solved, only to be replaced by another, with the pattern repeated again and again. It was the collective refusal of men to be discouraged by this relentless sequence that is important.

Seen in this light, Dunkirk remains, above all, a stirring reminder of mans ability to rise to the occasion, to improvise, to overcome obstacles. It is, in short, a lasting monument to the unquenchable resilience of the human spirit.

1

The Closing Trap

EVERY MAN HAD HIS own special moment when he first knew that something was wrong. For RAF Group Captain R.C.M. Collard, it was the evening of May 14, 1940, in the market town of Vervins in northeastern France.

Five days had passed since the balloon went up, as the British liked to refer to the sudden German assault in the west. The situation was obscure, and Collard had come down from British General Headquarters in Arras to confer with the staff of General Andr-Georges Corap, whose French Ninth Army was holding the River Meuse to the south.

Such meetings were perfectly normal between the two Allies, but there was nothing normal about the scene tonight. Coraps headquarters had simply vanished. No sign of the General or his staff. Only two exhausted French officers were in the building, crouched over a hurricane lamp waiting, they said, to be captured.

Sapper E. N. Grimmers moment of awareness came as the 216th Field Company, Royal Engineers, tramped across the French countryside, presumably toward the front. Then he noticed a bridge being prepared for demolition. When youre advancing, he mused, you dont blow bridges. Lance Corporal E. S. Wright had a ruder awakening: he had gone to Arras to collect his wireless units weekly mail. A motorcycle with sidecar whizzed past, and Wright did a classic double take. He suddenly realized the motorcycle was German.

For Winston Churchill, the new British Prime Minister, the moment was 7:30 a.m., May 15, as he lay sleeping in his quarters at Admiralty House, London. The bedside phone rang; it was French Premier Paul Reynaud. We have been defeated, Reynaud blurted in English.

A nonplussed silence, as Churchill tried to collect himself.

We are beaten; Reynaud went on, we have lost the battle.

Surely it cant have happened so soon? Churchill finally managed to say.

The front is broken near Sedan; they are pouring through in great numbers with tanks and armored cars.

Churchill did his best to soothe the manreminded him of the dark days in 1918 when all turned out well in the endbut Reynaud remained distraught. He ended as he had begun: We are defeated; we have lost the battle.

The crisis was so graveand so little could be grasped over the phonethat on the 16th Churchill flew to Paris to see things for himself. At the Quai dOrsay he found utter dejection on every face; in the garden elderly clerks were already burning the files.

It seemed incredible. Since 1918 the French Army had been generally regarded as the finest in the world. With the rearmament of Germany under Adolf Hitler, there was obviously a new military power in Europe, but still, her leaders were untested and her weapons smacked of gimmickry. When the Third Reich swallowed one Central European country after another, this was attributed to bluff and bluster. When war finally did break out in 1939 and Poland fell in three weeks, this was written off as something that could happen to Polesbut not to the West. When Denmark and Norway went in April 1940, this seemed just an underhanded trick; it could be rectified later.

Then after eight months of quietthe phony waron the 10th of May, Hitler suddenly struck at Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Convinced that the attack was a replay of 1914, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Maurice Gamelin, rushed his northern armiesincluding the British Expeditionary Forceto the rescue.

But Gamelin had miscalculated. It was not 1914 all over again. Instead of a great sweep through Flanders, the main German thrust was farther south, through the impenetrable Ardennes Forest. This was said to be poor tank country, and the French hadnt even bothered to extend the supposedly impenetrable Maginot Line to cover it.

Another miscalculation. While General Colonel Fedor von Bocks Army Group B tied up the Allies in Belgium, General Colonel Gerd von Rundstedts Army Group A came crashing through the Ardennes. Spearheaded by 1,806 tanks and supported by 325 Stuka dive bombers, Rundstedts columns stormed across the River Meuse and now were knifing through the French countryside.

The Miracle of Dunkirk FOR EDDIE RESOR

The Miracle of Dunkirk FOR EDDIE RESOR