1963 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

ISBN 08078-08741

ISBN 08078-45205 (pbk.)

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 6322810

09 08 07 06 05 15 14 13 12 11

THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY PRINTED.

For my daughters Becky and Meg

Preface

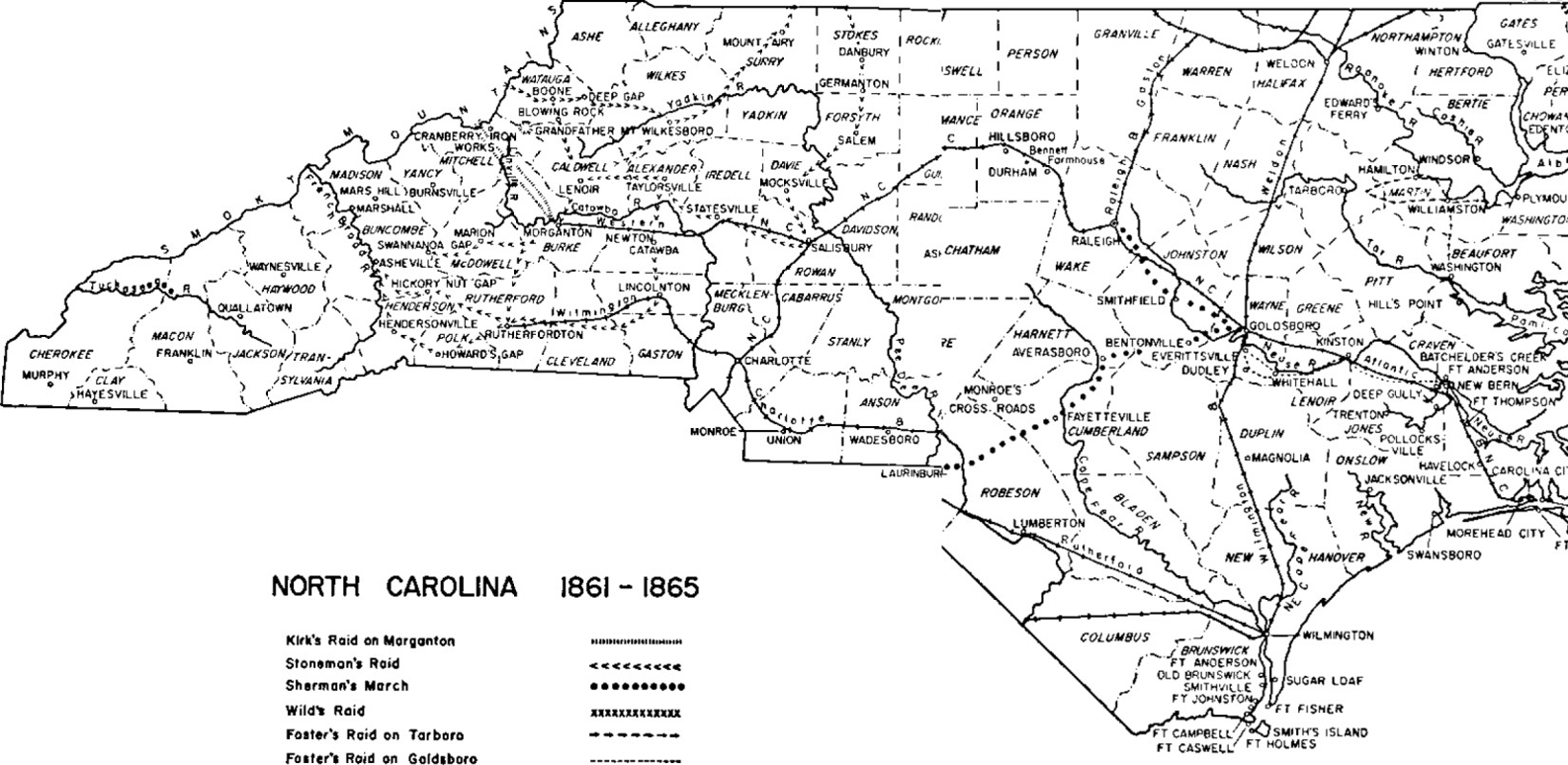

THE PRESENT STUDY is the extension of an earlier work, Shermans March Through the Carolinas. It became apparent in doing research for the previous volume that little has been written concerning the war in North Carolina. Invaded from the east, the west, the north, and the south, the state was the scene, nevertheless, of much fighting. Although the numbers involved in many of these operations were comparatively small, the campaigns and battles themselves were not unimportant in the grand strategy of the war. Lees operations in Virginia were controlled to a large extent by conditions in North Carolina. The historians failure to record adequately the fighting in the Tar Heel state, therefore, has left incomplete not only the story of the conflict in North Carolina but also that of the war in the eastern theater. In an attempt to correct these omissions the author has undertaken this work.

I have been most fortunate in the help I have received in preparing this study. A generous grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation made possible a years leave of absence from my teaching duties, and summer grants from the American Philosophical Society, Southern Fellowship Fund, University Center of Virginia, the Virginia Military Institute, and the Society of Cincinnati of the State of Virginia enabled me to complete all necessary research.

Sincere thanks go to Professor Hugh T. Lefler of the University of North Carolina and Professor Bates McCluer Gilliam of the Virginia Military Institute. These two scholars read the manuscript in its entirety and made invaluable suggestions.

In addition I am indebted to Cadet William M. Kolb of V.M.I. for drawing the maps, to the University of North Carolina Press for allowing me to quote fully from Shermans March Through the Carolinas and to Mrs. William O. Roberts of Lexington, Virginia, whose careful examination of the manuscript prevented many literary errors.

I am especially grateful to Miss Mattie Russell of Duke University, William D. Cotton of Pfeiffer College, and Charles L. Price of East Carolina College who very kindly allowed me to use their graduate theses. I also wish to thank Professor Robert H. Woody of Duke University for granting me permission to examine the work of several of his former students.

Special thanks go to Nat C. Hughes of Webb School, Colonel Paul Rockwell of Asheville, North Carolina, Tom Parramore of the University of North Carolina, and William T. Rutledge of the University of Virginia for making available to me valuable material on the Civil War in North Carolina.

The staffs of Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, the Manuscript Division of the Duke University Library, the North Carolina Department of Archives and History, the North Carolina Collection of the University of North Carolina, and the Preston Library of the Virginia Military Institute have all been extremely helpful.

My wife, Lute, had the unenviable task of typing the manuscript from a rough pencil draft. Without her endeavors, encouragement, and understanding this volume would not have been possible.

Lexington, Virginia John G. Barrett

October, 1962

Contents

CHAPTER I

Will There Be Civil War?

NORTH CAROLINA, a state in the upper South, did not play a leading role in the great secession drama of 186061. While the fire-eaters in South Carolina and the states of the lower South were talking secession, North Carolinians, for the most part, still favored the national Union. Since the soil of the state was not well suited for the growing of cotton, there were relatively few wealthy planters with large slaveholdings to agitate for a break with the Federal government.

On November 5, 1860, the telegraph flashed the word that Abraham Lincoln had won the presidency of the United States.

Lincolns victory triggered the secession of the states of the lower South. Yet in North Carolina there was little talk of secession. The great majority of people did not regard the election of a Black Republican, however distasteful, as sufficient grounds for withdrawing from the Union.

North Carolinas Governor, John W. Ellis, was not in the least surprised at his states cautious approach to secession. Back in October, 1860, he had written Governor William H. Gist of South Carolina that the people of North Carolina were far from being unanimous in their views and feelings concerning the action the state would take if Lincoln were elected president. Ellis said that some would yield, some would oppose Lincolns power, and others probably would adopt the wait and see attitude. Many of the people believed that the President would be powerless for evil with a minority in the Senate and perhaps in the House of Representatives; others said, however, that his election would prove a fatal blow to the institution of negro slavery in this country. The Governor did not believe that a majority of his people would consider Lincolns election as sufficient ground for dissolving the Union of the States.

With the people of North Carolina generally disposed to accept the results of the election and to await developments, the General Assembly met in Raleigh on November 19, 1860. The Governors message to this body was anxiously awaited throughout the state, since it was expected to outline the policy that North Carolina was to follow in this time of crisis.

Governor Ellis address was closely in accord with the thinking of the secessionists or radicals, who favored immediate action by North Carolina. Those who opposed the Governors program were generally classified as Unionists or conservatives. They saw no necessity for a withdrawal from the Union.

In the General Assembly, the message received an enthusiastic approval by the radicals, but a severe condemnation by the conservatives. Yet on the matter of military preparedness, these factions seemed to be in agreement. Both the radical and the conservative felt that the state must prepare itself for any eventuality. A $300,000 appropriation for the purchase of arms and ammunition passed the Senate on December 18, A military commission was established to help the Governor administer the funds.

While the legislative halls resounded to heated debate, public opinion throughout North Carolina reached a fever pitch, primarily as a result of the growing strength of the secession movement. As early as November 12, 1860, a secession meeting had been held in Cleveland County.

In the midst of this agitation for a convention, South Carolina, on December 20, withdrew from the Union. In strongly secessionist Wilmington, the news created great excitement. As one hundred guns fired a salute to South Carolina, the streets filled with an anxious citizenry. On every corner groups of men could be seen engaged in serious converse upon the one topic of the day.

Although South Carolinas action was strongly denounced in many quarters of North Carolina, the people of the state stood united in opposing the use of force to bring the seceded state back into the Union.