This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1900 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

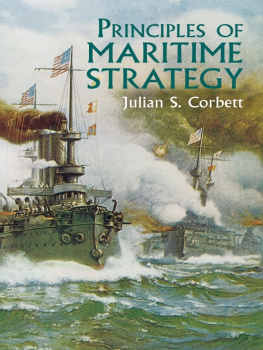

THE SUCCESSORS OF DRAKE

BY

JULIAN S. CORBETT

Author of Drake and the Tudor Navy , etc.

WITH PORTRAITS AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

THE present work is designed as a sequel to Drake and the Tudor Navy, to which it practically forms a third and concluding volume, carrying the reader through the period of hostilities with Spain which extended from the death of Drake in 1596 to the conclusion of the war at James I.s accession. It is a period which, if we except the operations of Essex at Cdiz in 1596, has been much neglected by historians and as much misunderstood. The years in which it is included have been thus summarised by one of the highest and most recent of English authorities. Between 1588 and the death of Elizabeth there intervened fifteen years. So long the war lasted, which on the side of England was chiefly a series of plundering expeditions in which the Government scarcely aimed at a single national object, but rather allowed naval adventurers to make reprisals for their exclusion from the New World. It is a peculiar and unique period of English history, in which war is waged, but freely, with a triumphant sense of power, with scarcely any sense of danger, with some lawlessness, yet on the whole with a good conscience and with a national pride which no earlier generation had known. The glory of 1588 tinged every succeeding year of the war; the sense of danger and the tension that had held the national mind for a whole generation was gone, and a new generation grew up to revel in victory and discovery. {1}

That this passage fairly represents the prevalent view of the last decade of Elizabeth will not be denied. Yet to those who have patience to examine the time more closely it will seem curiously, even perversely inadequate. They will find that the period which is represented as one of triumph, security, and random buccaneering was the period which saw the birth of the Spanish navy, which saw such comprehensive and well matured attempts as the campaigns of 1590 and 1597, which saw a new Armada off Ushant, which saw Spinola at Sluys and Spanish naval stations established from end to end of the Channel, which saw the invasion of Ireland and the English cruising squadrons again and again driven of their ground by superior force. Nor is the one event that is ever dealt with in detail presented in a truer light. The same writer quotes our first authority in naval history as saying that the Cdiz exploit was the Trafalgar of the Elizabethan war. In a sense perhaps it was, for it was the last naval victory; but in the following years Spain was able to dispatch two Armadas against England and a third one would have sailed but for the action of the Dutch; nor to the wars end could the English navy ever get command of the Spanish trade routes. So far from being a crowning success it was rather an irretrievable miscarriage, that condemned the war to an inefficient conclusion.

In truth the whole period is one of splendid failures, and it is this very consideration which makes it so well worth study today. For it is the period during which England attempted to use the maritime supremacy she had obtained, and the conditions and causes of her want of success are full of a deep and living interest such as the largest measure of victory could hardly have afforded.

Mainly the work is concerned with naval history, hut not so exclusively as the two previous volumes. Military affairs begin to intrude themselves. Indeed it is doubtful whether the naval and the military history of England should ever be written apart. The real importance of maritime power is its influence on military operations. This is the thesis which lies at the bottom of all the teaching with which Captain Mahans name is pre-eminently associated. To forget it is the chief danger of the heresy which Elizabethan soldiers vainly derided as the idolatry of Neptune. The direction of a great war can only be followed out in the mutual reaction of the two forces, and how closely they are inter-dependent nothing shows more emphatically than the last years of the Elizabethan war. It is impossible to deal adequately with the naval operations without understanding what the soldiers were doing. To treat, for instance, of the action of the fleet during the Spanish descent on Ireland in 1601 without following the strategy ashore might be naval chronicling. It would not be history.

But there is yet another reason why military affairs intrude. The great lesson that the period teaches is the limitation of maritime power. The power had been gained and was appreciated, but to everyones surprise it did not produce the expected results, and neither the Queen nor her Government could understand the reason. The navy maintained a high level of efficiency. It was almost continually at work under fairly capable officers, and yet the war seemed to draw no nearer to its end. It was not seen that there is a point beyond which hostilities by naval action alone cannot advance. It was an army that was wanting. Some there were who saw where the hitch lay, and under Essexs influence they succeeded hi procuring some kind of reorganisation of the land forces. Ostensibly it was done with a view to coast defence, but the real object of Essex and the military reformers was to form a corps ready trained and organised for service beyond the seasa force that could reap where the fleet had sown. The consideration of this movement, then, becomes essential to a right judgment of what the navy achieved, and what it left undone.

Nor must it be forgotten that the most famous of Drakes successors, Essex, Ralegh, Vere, and Mountjoy, were all soldiers. They brought to the handling of the navy a soldiers conception of warfare. They viewed the fleet, not as a separate entity, but as an integral part of one great force, in a way that it had never probably been regarded before. Indeed, it is not too much to say that the campaign in which Mountjoy and Carew saved Ireland affords the first example in modern history of a naval force being rightly used by a military commander as a fourth arm.

There is one more curious misconception pervading the period which can only be referred to with regret and disappointment. An almost universal idea exists that in the last years of the war Sir Walter Ralegh played some high and heroic part. Yet one seeks for its justification in vain. By the majority of his contemporaries he was regarded as a Jonah and a marplot, and the more closely the period is studied the more reason they seem to have had for their opinion. They even accused him of a want of staunchness at sea, and, however far we may be from sharing their personal dislike of him, it is difficult to find a means of defending him against the charge. Judged by what he wrote in later years, Ralegh appears a statesman, a strategist, and a Christian hero, but when we seek for his fruits in action the effect is sadly different.