Praise for Hell or Some Worse Place

a detailed narrative filled with heroism, treachery, dynastic politics, and adultery the makings of a soap opera, except that all of it actually happened. Publishers Weekly

the authors gift for deep, comprehensive historical study and his ability to keep characters fresh in readers minds bring this battle between Spains best general and Queen Elizabeths favourite, Charles Blount, to the awareness it has been denied A fantastic book that finally assigns Kinsale its rightful place in history. Kirkus

lively and enthralling Ekin is a wonderful guide through this engrossing tale

Sunday Times

Praise for The Stolen Village

Des Ekins bestselling book on the taking of slaves from Baltimore, County Cork, by the Barbary pirates

Shortlisted for the Irish Book of the Decade award 2010

An enthralling read, not simply for the story of the raid itself, which Ekin recreates with bloodcurdling vividness, but for the parallels the author draws with the current geo-political situation. The Irish Times

an irresistibly readable narrative a compelling book. The Scotsman

This is a gripping account thats exhaustively researched but wears its learning lightly, and proceeds along at a lively pace proof, if it was needed, that fact is often more interesting than fiction. Metro

It is one of the great adventure stories of history a siege drama that deserves to rank alongside the Battle of the Alamo and the heroic defence of Rorkes Drift against the Zulu nation.

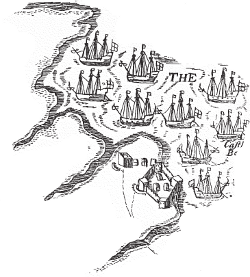

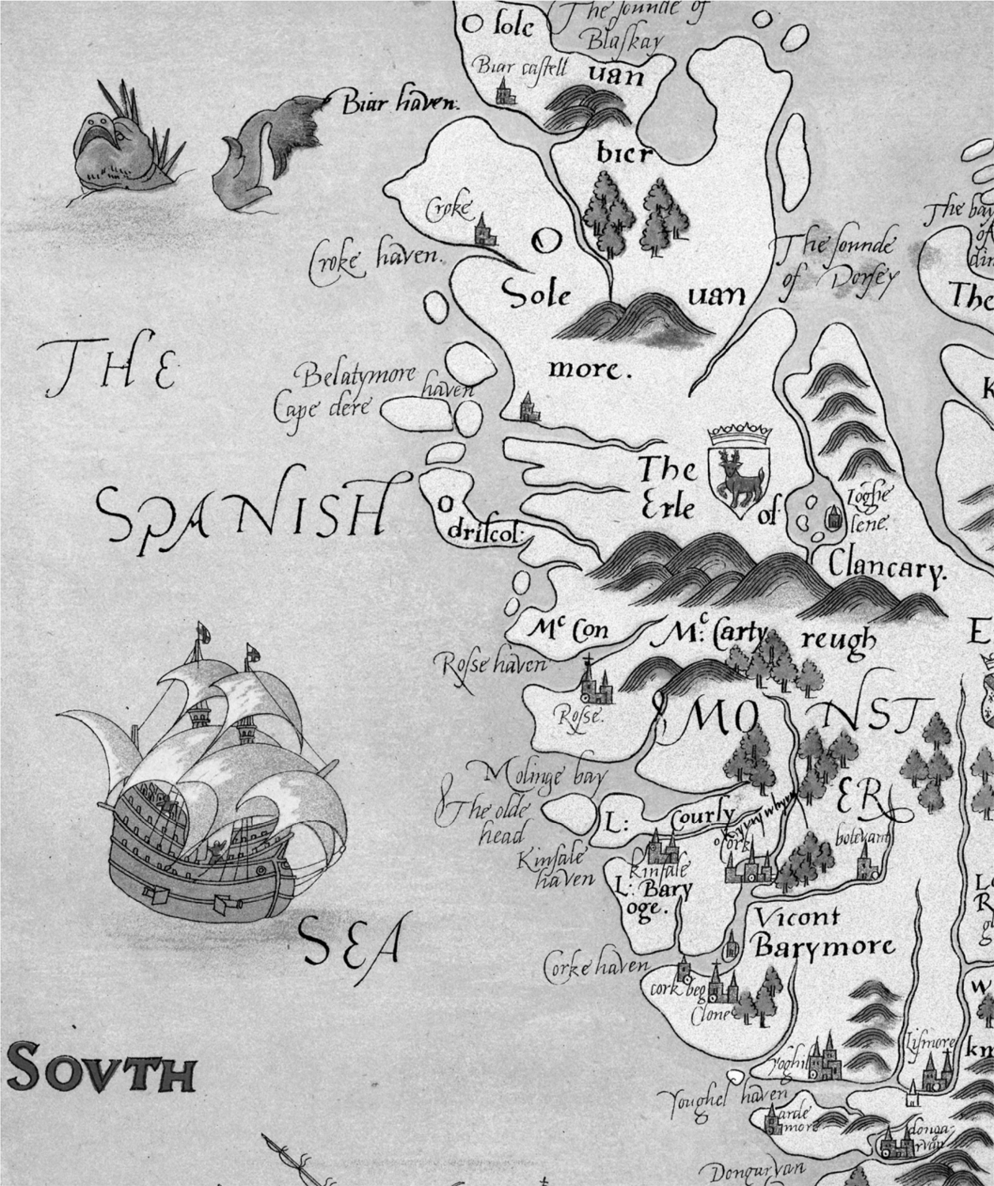

At 6pm on 21 September 1601, one of the strangest invasion forces in history sailed into the southern Irish harbour of Kinsale, a place its commander had never wanted to go. Battered by punishing storms and towering waves, it had lost contact with its best ships, most of its troops and some of its most important supplies. Although its ostensible purpose was to fight its way through Ireland and conquer England from the west, the expedition included hundreds of women and children. Its ranks contained scores of petrified young soldiers who had no idea how to shoot a gun. It had 1,600 saddles but no horses to put under them.

This was the last of the great armadas of the Elizabethan era and the last Spanish armada ever to attempt an invasion of England through Ireland.

As the boats dislodged the 1,700 weary troops and the seasick civilians onto shore, the open-mouthed townspeople also saw a gaggle of nuns in their wimples and veils (and perhaps an occasional starched cornette) trip delicately across the rock and shingle. They were followed by a succession of bizarre religious figures. There was a much-feared Jesuit secret agent who was wanted by the English for allegedly organising a murder plot against Queen Elizabeth. There was a Franciscan friar whod been appointed as Archbishop of Dublin a city he would never visit, and a See he never saw. There were two more bishops, and a confusion of priests and friars. In this strange guns-and-rosaries expedition, the clerics enjoyed huge power. They immediately tried to order the veteran soldiers around. Even when it came to military matters, they felt they knew best.

As the townspeople soon found out, this wasnt even purely a Spanish expedition. The ships an odd mix of serious warships and requisitioned merchant vessels hauling cargos like salt and hides carried a multinational mix of Spanish, Italians, Portuguese, Irish insurgents, and even a few English dissidents. Yet this oddball force was destined to be the most successful Spanish invasion ever mounted against England. Unlike the renowned Great Armada of 1588, this expedition actually established a bridgehead on English-controlled territory and captured a string of key ports.

The maestro de campo general or overall land commander of the expedition was an intriguing veteran named Don Juan del guila. Today, he is relatively unknown. And yet guila was the commander responsible not only for this last Spanish invasion of Ireland at Kinsale, but also, a few years earlier, for the last Spanish invasion of England: a daring incursion into Cornwall from his base in Brittany.

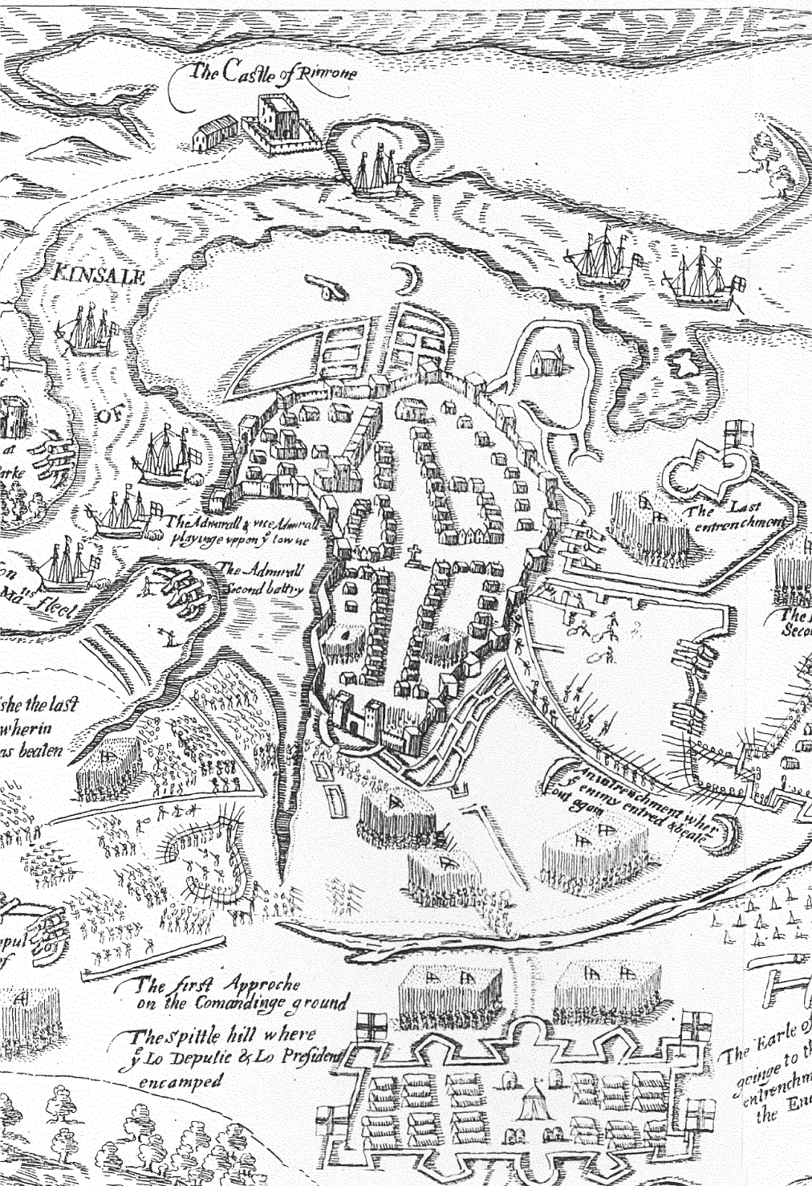

guila held out in the walled city of Kinsale for a hundred days, enduring a crippling siege imposed by English commander Charles Blount. Pinned down in one of the least defensible towns in Europe, the Spaniards shivered and starved under the relentlessly pounding English artillery and the equally pitiless Irish weather.

Monstrous guns hurled down fire and death from the hills into the narrow streets. Cannonballs tore breaches in their walls. Besieged from sea and land, the invaders had been reduced to eating dogs, cats and knackered horses indeed, those were described as treats and the best victuals within the town. Their troops died in their hundreds from hypothermia, malnutrition and dysentery.

Yet they held out and never surrendered.

There were bitter disappointments for the invaders: the locals initially gave them little help, despite confident promises; reinforcements despatched from Spain failed to get through to the town; and a huge relieving force of Irish insurgents from the north of the island proved unable to smash the siege and unite with their beleaguered allies. Still, even after the Irish rebel force was routed at the Battle of Kinsale, and all hope of success had been dashed forever, the surviving invaders still clung grimly on, declaring their determination to die before surrendering the town.

With both sides battle-wearied, and neither relishing the idea of a bloody hand-to-hand fight through Kinsales narrow and claustrophobic streets, guila eventually came to terms with his English counterpart. The proud Spaniard sailed home, undefeated, with his sword still at his side and his colours still flying. An honourable man, he insisted on one particular condition that almost broke the deal: although the English wanted to arrest and hang the Irish traitors whod fought on the Spanish side, he refused to hand them over.