Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by John R. Maass

All rights reserved

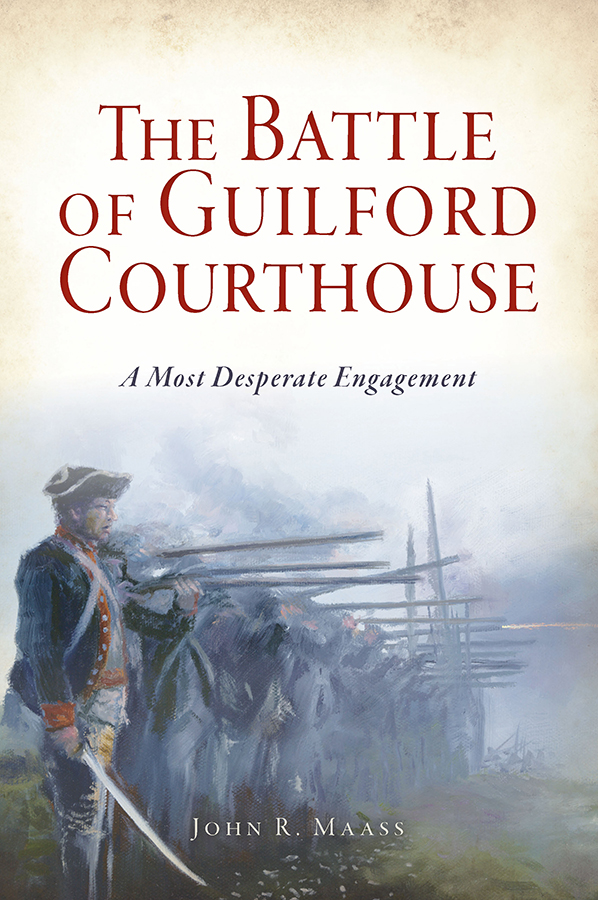

Front cover image courtesy of White Historic Art.

First published 2020

E-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43966.920.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954281

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.912.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to the Washington and Lee University class of 1987, of which the author is a proud member.

Non incautus futuri.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book is not produced by the author alone. Many generous people and organizations helped me research and write this book over the past few years, and I wish to express my sincere thanks to them. These include Charles Baxley, Jim Piecuch, Cheryl Bratten, Joshua Howard, Paul Morando, Robert Orrison, James Tobias, Erik Goldstein, John Durham, Scott Douglas, Mark Bradley, Jay Callaham, Glenn Williams, Patrick Jennings, Todd Braisted, John Beakes, Jeff Lambert, Ellen Clark, the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution, the U.S. Army Center of Military History, the National Museum of the U.S. Army, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, and the Society of the Cincinnati (Anderson House).

I wish to express particular appreciation to Jeff and Amy Oves of Kernersville, North Carolina, for graciously hosting me for a weekend while I took photographs for the book and visited obscure historical sites, and to Barbara Bass of South Boston, Virginia, for leading me on a tour of The Prizery exhibits and the site of Boyds Ferry on the Dan River.

INTRODUCTION

Let me still hear the Cannons thundering Voice,

In terror then run; that sweet noise

Rings in my ears more pleasing than the sound

Of any music consort that can be found

Then to see legs and arms torn ragged fly

And bodies gasping all dismembered lie.

George Lauder, The Scottish Soldier, 1629

In the thinly settled North Carolina Piedmont, a rough highway known as the Great Salisbury Road led late eighteenth-century travelers westward from Hillsborough on to the crossroads village of Salisbury on the Yadkin River, ninety miles away through a rolling, thickly wooded country with few towns, scattered farms, and numerous creeks and rivers. One of the small rustic villages along this well-used sandy road was Guilford Courthouse, the judicial seat of the backcountry county of Guilford, recently formed in 1771. A small log or wooden frame courthouse and a tiny jail were erected there in 1774, at the junction with Reedy Fork Road, which led northward.

Around Guilford Courthouse in the late winter of 1781, the quiet forests of the hilly sylvan countryside, populated in part by peaceful Quakers as early as the 1750s, were suddenly shattered by the booming thunder of cannon fire, musket volleys blasting in the bare woods, and the anguished shouts and cries of thousands of men in two weary armies aiming to destroy one another. This violent clash was fought on a cold, wet afternoon on March 15, during which American forces under Major General Nathanael Greene engaged Lieutenant General Charles, Lord Cornwalliss British army in a bitter two-hour contest that was, in Greenes poignant words, long, obstinate, and bloody.

The frightful contest at Guilford was a severe conflict and produced heavy casualties. The troops made repeated use of their flintlock muskets, steel bayonets, and dragoon swords in hand-to-hand fighting, which killed and wounded about eight hundred men. Some soldiers fled the field in terror, while others played dead on the ground to avoid capture. Several participants in the grueling battle wrote that for much of the ferocious contest, it was long in doubt which side would emerge the victor, so fierce was the struggle. In the end, however, a cautious General Greene withdrew his battalions from the battleground, letting Lord Cornwallis claim a victory. Except [for] the honor of the field[,] they have nothing to boast of, Greene said.

It soon became painfully obvious that the British triumph was pyrrhic. Hundreds of redcoats lay dead and wounded in the damp fields and forests, while the rest of the kings troops were too drained to pursue the rebels with any strength as a steady drizzle began to fall. After two days, the Americans saw the odd circumstance of a triumphant enemy general marching his men away from the site of his bloody victory, limping toward the far-off Carolina coast and giving up the fruits of hard-fought operations. It would not be the last time Greene and his army would miss out on a victory on the battlefield or siege lines but emerge the victors nonetheless.

The campaign leading up to the Battle of Guilford Courthouse was strenuous, dramatic, and long in doubt. While Greenes army could not claim a triumph after the Guilford battle, as many veterans and civilians later called it, two and a half years later they watched British forces evacuate their long-held garrisons in the South after American independence was secured. As it turned out, the ferocious battle that raged around the little courthouse hamlet in North Carolina that winter day was one of the most critical factors in securing that liberty in the newly created United States.

Prologue

THE HIGHEST HONOR TO YOURSELF

The South Gets a Yankee General

I only lament that my abilities are not more competent to the duties that will be required of me.

Major General Nathanael Greene, October 1780

In the early fall of 1780, the American Revolution seemed to be at a low point for the Patriots. General George Washington, the Continental Armys commander-in-chief since 1775, found himself and the cause of independence in a whirlwind of danger and conspiracy. One of his most capable and trusted subordinates, the mercurial Major General Benedict Arnold, had just been unmasked as a traitor after trying to give over the key American defensive post at West Point on the Hudson River in New York to the British in September. Moreover, after his abortive attempt at treachery, Arnold fled to an enemy ship anchored in the river, a deceitful act that left Washington enraged and astonished. It was, Washington wrote, a scene of treason as shocking as it was unexpected. The American commander also feared that the enemy may have it in contemplation to attempt some enterprise against the run-down defenses at West Point, and he worked feverishly to secure the post from potential British attacks.

As part of Washingtons effort to hold the vital Hudson River defenses during the chaotic scene after Arnolds duplicity, he appointed thirty-eight-year-old Major General Nathanael Greene as commander at West Point and ordered him on October 6, 1780, to bring two divisions of Continental soldiers there. Greene, having long desired this assignment, gave orders the next day for his troops to move northward from their camps at Haverstraw, New York, on the west bank of the Hudson, about thirty-five miles north of New York City. When Greene and his soldiers arrived at West Point, they found the fortifications in a miserable situation and the defenders woefully short on food and forage. The deplorable state of the earthworks and the garrison resulted from Arnolds neglect, part of his secret plan to allow the British to take the post.