INTRODUCTION

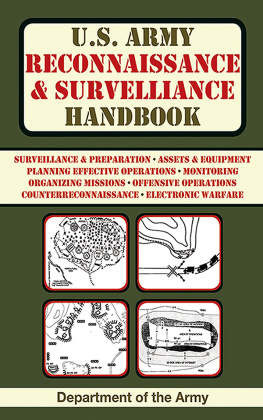

R ECONNAISSANCE HAS LONG BEEN A KEY tool to enable military commanders to obtain a picture of the tactical situation and to make informed decisions. An early example of this can be found in the scouts drawn from the people known as Sciritae who were deployed by the Spartans and had a privileged position in their order of battle. The Spartans were so aware of the advantage that their sentinels and scouts gave them in military operations that they went to great lengths to keep them secret. As military tactics, weapons and equipment developed over the centuries, methods of scouting and reconnaissance evolved and adapted, but were never discarded.

From the highly toned Spartan warriors, through the scouts employed by Julius Caesar, through the Middle Ages, to the Napoleonic Wars and the mass warfare of the modern era, this book aims to provide a concise but revealing picture of the art of military scouting and reconnaissance, always remaining true to the spirit of the scout light on their feet, taking only what they need and returning with, or sending back, information that could make the difference between victory and defeat. The scout cannot expect to see everything; it is up to the intelligence experts and commanders to interpret it.

Scouting and reconnaissance responsibilities are carried out by several different military units, some of which are dedicated to reconnaissance, and others which include reconnaissance as part of a wider brief. For example, the United States Marine Corps combine two activities in one with their scout/sniper teams, based on the logic that a snipers covert skills also places them in a good position to gather intelligence. Special forces units tasked with a mission which may include direct action are also well placed for reconnaissance.

In the first chapter, I look at the development of military scouting and reconnaissance by the ancients, focusing particularly on the use of scouting and decisive action by Julius Caesar during the Gallic wars and by Alexander the Great, king of Macedon. It will not take long to appreciate how information gleaned from their intrepid scouts and their own aptitude for decisive action contributed to their success in battle.

During the medieval period, reconnaissance was carried out in various ways, including by light cavalry. The battle of Hastings (1066) was but one example of how early information about the dispositions of the opposing force gave the Normans the edge over the English army which, fighting on its own familiar ground, may have been thought to have the advantage. Richard the Lionheart used light cavalry during the crusades to determine the position of Saladins armies.

During the American wars (American Revolutionary War 17751783; War of 1812), backwoodsmen familiar with hunting techniques and the ways of the native American Indians made excellent scouts for military commanders. Frontiersmen like Daniel Boone 17341820), sharpshooters like Timothy Murphy (17511818) and Daniel Morgan (17361802), founder of Morgans Riflemen, came to the fore as well as new reconnaissance units such as Rogers Rangers formed by Major Robert Rogers (17311795). This chapter describes the growing appreciation of the value of these mobile forces, which were able to blend into the environment and appear when and where they were least expected.

In the Napoleonic era (18001815), large bodies of men marched in columns in the open, often in brightly coloured uniforms, but the value of skirmishers was also appreciated. This chapter looks at the development of units such as the French Voltigeurs and Chasseurs , and the British light infantry, as well as Napoleons use of Cavalry Scouts in the 1814 campaign, the final campaign of the War of the Sixth Coalition.

Although Napoleon had his eye on India and hoped to enlist Russian support, changes in loyalties and alliances meant that a Great Game was played out between Britain and Russia as they struggled for influence in Afghanistan. Here, British and Russian army officers, often in disguise, embarked on extended reconnaissance missions to gather information about enemy movements and possible invasion routes in the remote Afghan mountain passes. This story would continue to repeat itself to the present day and unfortunately many of its lessons would remain unlearned.

The British Army entered a sharp learning curve when it confronted the Boers of South Africa (18991902). These hardened men used to hunting on the veldt were hard to defeat on ground that they knew like the backs of their hands. During the Matabele wars (16931894; 18961897), men such as Frederick Russel Burnham, who had learned his trade among the American Indians and the Apache Wars (18491886), Robert Baden-Powell and the hunter Frederick Courtney Selous made their mark. Burnham was so highly valued by the British Commander-in-Chief General Roberts that, despite being American, he was made Chief of Scouts of the British Army.

The Germans began the First World War (19141918) with better trained and more effective snipers than the British, who had to learn the hard way in order to adapt. Soon, a British sniping school was set up and the arts of reconnaissance and camouflage were honed. Despite the relatively static nature of trench warfare, patrols into No Mans Land at night, and later during the day, often yielded valuable intelligence. Having made themselves useful during the Boer War (18991902), the Scottish Highland yeomanry regiment formed in 1900 and known as the Lovat Scouts continued to distinguish themselves with their unique observation and tacking skills in the Great War.

Apart from the scouts that were part of regular military squads and platoons, specialised units were formed during the Second World War (19391945), with specific missions to operate behind enemy lines. These included the US 6th Army Special Reconnaissance Unit Alamo Scouts, six- or seven-man teams who operated behind enemy lines in the Pacific Theatre; the British Long-Range Desert Group (LRDG), which operated against German and Italian forces in North Africa; the Special Air Service (SAS), which, beginning in North Africa, spawned French, Belgian and other associated units that were parachuted into France in advance of the Allied invasion of Normandy in 1944; the Lovat Scouts and US Army Rangers.

The non-global conflicts of the Cold War era in regions such as Vietnam and Malaysia, underlined the need for mobile forces with an intuitive understanding of terrain and local people. The role of special forces grew in importance while nuclear confrontation remained unthinkable. In Malaysia, Borneo and Vietnam, special forces honed their patrol skills and their ability to harness the knowledge of local populations.